This article was originally published on Aug. 13.

There is no Minor League Baseball in 2020, but player development continues even (and especially) when you add the third deck to the stadium. The biggest jump in organized baseball is from Triple-A to the majors. Prospects who get the call must continue to improve and adjust to thrive against the best arms and bats the sport has to offer. This series will take a look at how recent prospects of note are faring in the big leagues, and what they need to continue to develop in order to make their OFP a reality.

The Story So Far

There’s been no shortage of Dustin May coverage at Baseball Prospectus since the Dodgers drafted him in the third round of the 2016 draft. He developed quickly from a projectable Texas prep arm into a top pitching prospect with a plus, flashing plus-plus fastball/curve combo. He never really found a consistent third pitch in the minors, but the top two flashed so good that it didn’t matter. In his first go-round in the majors, May struggled to command his power breaker and relied primarily on a low-90s cutter that didn’t cut a ton to complement his mid-90s whiffle ball two-seamer. The Dodgers were very conservative with his usage, so despite having a strong durability track record in the minors, there were open questions about how the overall arsenal would work deeper in games. Nevertheless we ranked him as the top right-handed pitching prospect and eighth overall.

Let’s go to the tape

I coined the Gingergaard nickname sometime in 2017 as half demographic comp, half groan-worthy portmanteau. But May was always a good projection bet, and his year-over-year velocity gains have continued. His wicked running two-seamer now sits 97-100, as the Giants quickly found out on Opening Day.

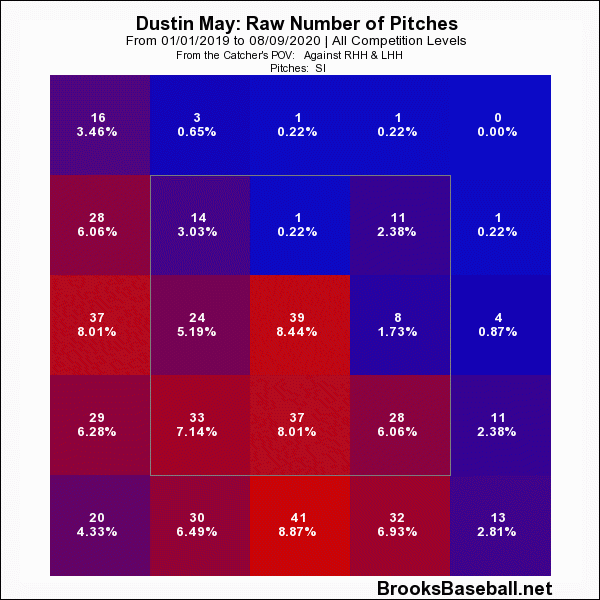

This is a no-shit 80-grade sinker. May has the second-highest velocity of any starting pitcher in 2020, and he can spot the fastball down in the zone to either side of the plate. He’s generally been more strikethrower than command artist, but so far this season he’s moved the fastball around the zone well. Our launch angle era has caused sinkers to fall out of favor, but with May it’s like trying to elevate a kettlebell. Watch Jose Altuve keep his hands in and put a nice swing on 99 just off the inside edge and only manage a soft two hopper on the infield.

If you want to nitpick, it’s not your en vogue high-spin four-seam up in the zone. And unsurprisingly, May rarely elevates it.

So his whiff rate on the sinker is a shade under six percent for his major-league career. By contrast, Jacob deGrom—the only harder throwing starter in 2020—has a near 14 percent whiff rate on his four-seam fastball since the start of 2019. May came up through the minors as a very modern pitching prospect—high spin four-seamer up, 12-6 curveball down. He switched to the two-seam in 2018, but the original breaking ball was still present in his big-league debut against the Padres.

May barely threw the curve in 2019—struggling to command it when he did—then ditched it entirely for a power slurve[1] in 2020. His primary secondary offering, both then and now, is a cutter, a third recent addition to his repertoire. This makes sense in combination with the two-seamer. It gives May something he can use to get in the kitchen of left-handed batters and a different glove-side look, right on right. The cutter’s velocity has ticked up along with the fastball, averaging 93 mph this season. And when it flashes, it’s a monster, featuring late, two-plane action combined with what’s essentially average *fastball* velocity.

This is unfair and unhittable, the kind of pitch that will make the batter take a brief stroll to collect his thoughts. To continue our not-a-comp, it wouldn’t stand out remotely in a montage of deGrom’s best sliders. But herein lies the limitations of GIFs. I enjoy the comical swing-and-miss shit that rolls down my twitter feed from @PitchingNinja and others, but it’s of little analytical value. Even if I was doing more extensive video work than I normally do, I’d be leery of using GIFs extensively. Because I can take the six or seven best pitches in an outing from an average A-ball starter, cut them together, and make him look like a future ace (finally putting that film degree to use, Mom and Dad). As good as the above cutter from May is, you also get too much of this, where he gets under the pitch and it just kind of spins up in the zone.

Or sometimes you get something that looks like an average four-seamer with minimal bore.

And then there’s the one that definitely never ends up on your Twitter feed.

And the median looks something like this:

Flashes plus is not plus as I often write, and May’s cutter is not a consistent swing-and-miss offering for how much he uses it. It might get there, and it is a better pitch now than it was at this time last year, which is a positive trend line given how recently he started using it. And the cutter doesn’t need to move a ton given the velocity and how it will tunnel off the fastball. He can get hitters to pull off it with just a bit of glove-side wiggle, but I wouldn’t even call it an average offering yet.

The new breaking ball already projects better. Call it a curve, slurve, slider, it’s more consistent in shape and swing-and-miss potential.

But there are growing pains here as well. The feel for the pitch isn’t as advanced as the cutter. May can struggle to start it in the zone, or get too much on the side of it causing it to stay on the same plane. I would like to see him start to work it in more than 10 percent of the time as he’s shown some facility to spot it for strikes already, and it gives him a different, slower look to help disrupt the batter’s timing even when it isn’t flashing plus. I suspect this is a pitch that will mostly stay in the holster until he refines it in side sessions however.

A brief note on durability and mechanics

I mentioned at the outset that May had an issue going deep into games during his 2019 debut. That’s continued in 2020, although it’s difficult to separate out efficiency/durability issues from broader starting pitching usage patterns, and the Dodgers as an organization tend to have a shorter leash with their less-tenured arms given their pitching depth. It’s also possible May is only now fully stretched out as his Opening Day start was unplanned. He went six innings and 80+ pitches his last two starts, which is conservative, but something the Dodgers might do regardless of how he looked in an outing. And while he does tend to bleed some velocity across his starts, generally the stuff has held up deeper in games

There are few durability concerns in the frame or mechanics. May remains on the slim side, but he’s gotten bigger and stronger this year and threw more than 120 innings in 2017, 2018, and 2019. That’s about the heaviest usage you are going to get in modern pitching development. Despite his long limbs, big leg kick, and what our editor-in-chief coined as “Waluigi energy,” May has no reliever markers in the delivery, repeats well, and fills up the zone. The only question remaining is if the secondary stuff develops enough to turn over a lineup multiple times across 32 starts. It’s not there yet, but I’d expect both the cutter and breaking ball to end up at least average. That should be enough when you are working off an elite fastball.

May is not going to win you the strikeouts category in your roto league—which might cause him to be underrated relative to his top line results—but as he passes out of my purview, I’m pretty comfortable reiterating that 70 OFP one more time.

One instructive at-bat

- v Tommy Pham, T2 (8/4/20)

One of the oldest pitching adages is get strike one. When you can spot it inside black at the knees at 98, you’ll get a lot of strike ones. May has now opened up a few different options, but elects to double up with the sinker, taking it down and out of the zone this time.

It’s not a strike, but it starts in the zone and Pham won’t want to go down 0-2. The best he might do with this is beat it to second base or shortstop. The sinker moves so much that it sets up a cutter away.

This is not a good cutter in a vacuum. It’s in the general vicinity of the median cutter pictured above. It perhaps nips a little glove-side, but when your fastball has as much arm-side movement as May’s, you’ll get your fair share of uncomfortable swings on a cutter a bit too high and that gets a bit too much plate. Now if that pitch is refined with a bit more tilt, it will play up anymore. It’s a three-pitch strikeout against an above-average major league hitter, but it tantalizes you with further possibilities as well.

Last Call at the Prospect Saloon

Dustin May, RHP (Los Angeles Dodgers)

The story of May’s development into a major-league starter is a bit atavistic, ironic since it occurred in one of the more analytically-inclined player development systems in the game right now. Drafted as a projectable Texas prep with a high-spin fastball and a big downer curve, May shifted into a sinker/cutter pitcher in recent seasons despite success in the low minors with his amateur arsenal. He’s never really developed a change-up, and the curve has morphed into more of a power slurve in 2020. The sinker has added even more velocity than we’d have projected—The Gingergaard nickname ending up life imitating a term of art—and he now sits in the upper-90s with elite two-seam movement and sink. The command lags a couple grades behind the movement, but May is effective working the pitch to both sides and generally keeps it down in the zone. It will get him quick outs and weak ground balls even against the best hitters in baseball.

His hard cutter is the preferred secondary. It’s got essentially above-average fastball velocity, which allows him to get away with ones that don’t move much or sit up in the zone, but it can lead to inefficient outings as it’s not hard to foul off when it’s not moving much. May can lack a putaway pitch in general as his breaking ball is inconsistent, although it does routinely flash plus. It’s more likely to get to above-average than the cutter, but I’d expect both to settle into 50 or 55 offerings. The overall profile looks to be a number two starter you keep waiting to truly break out into an ace, but that’s a helluva pitcher, even if the shape of the stuff is very different than what we would have expected when we first decided to strap a rocket to him.

[1] It’s been called both a slider and a curve, while BrooksBaseball and Baseball Savant classify it as a curve. And at various points in 2019 the cutter was called a slider by various sources as well. Anyway, as Craig knows I don’t argue about breaking ball nomenclature anymore, but it’s a distinct and different pitch this year.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now