This article was originally published on March 23.

On March 12, Major League Baseball belatedly made the decision to delay the start of its season for at least two weeks in response to the growing COVID-19 pandemic. Since then, that delay has grown to at least eight weeks in accordance with CDC guidance. Even once it is safe to play baseball, teams will need time to ramp up, given the interruption in physically preparing players for the season.

To put it bluntly: this sucks. It’s a bummer to imagine a spring with no baseball, let alone an entirely lost season. As we continue to assess and reassess an ever-changing situation, there are innumerable questions baseball must answer. How will service time be handled? How will player bonuses and incentives be allocated? What will happen to the minor league players, already underpaid, living paycheck to paycheck? What of stadium staff? If baseball does start, what will the schedule look like? The rosters? The playoffs?

More important than any of those questions, more important than baseball, is the necessity of implementing public health interventions to protect the populace from this growing pandemic. The situation has changed dramatically since Stephanie Springer wrote in the early stages of COVID-19’s arrival in the United States; the country is experiencing community spread. States have ordered casinos, gyms, bars, restaurants, and other public establishments to temporarily shut their doors. Public schools, libraries, and colleges and universities are closed as well, and companies and organizations have instructed their employees to work from home.

You have likely heard the term “social distancing” in the news, on social media, and among family, friends, and colleagues, as it pertains to these measures. Conceptually, it’s easy to understand: Limit your contact with others and avoid gathering in large groups to contain the spread of the virus. But humans are, by their nature, social creatures, and for many people what is hard to conceptualize is exactly why seemingly drastic measures are necessary when the number of cases is still small relative to the total population of the country. Some have gone as far as to call it an overreaction.

But it is not an overreaction. You have also likely heard the term “flattening the curve” frequently as of late; this is where that idea comes in. What exactly are public health experts referring to when they say that we must “flatten the curve”?

According to epidemiologists, it is possible that 20-60 percent of the adult population worldwide will—knowingly or unknowingly—be infected with coronavirus during the course of this pandemic. That is certainly a scary number. Outbreaks like this follow exponential growth curves. For SARS-CoV-2, the R0 value is estimated to be about 2.2—meaning that every infected person infects an additional 2.2 people, on average. “If the number of cases were to continue to double every three days, there would be about a hundred million cases in the United States by May,” according to a recent Washington Post article. The same article ran simulations, visually representing the spread of a theoretical disease and how its course would be altered by various interventions, including forced quarantine and various degrees of social distancing.

We don’t have the power to stop the spread of COVID-19, but we have the power to change the shape of its curve. Social distancing is not just about reducing the number of cases. It is about reducing the speed of the outbreak. By practicing social distancing as quickly and as ubiquitously as possible, we may not reduce the total number of cases, but we can slow down the rate of the pandemic. If the growth curve is left unchecked, hospitals have to care for too many patients at once and the number of new cases outstrips the number of ICU beds and ventilators available. We’ve already seen this happen in places like Italy, which is suffering the consequences of not acting preemptively. There are already rumblings in the United States that resources are “a fraction of the capacity that will be needed.”

Situations in which the healthcare system is unable to keep up are where death tolls rise—a lesson learned from past epidemics. More troubling still, the United States cannot even properly assess the situation due to the lag in testing compared to countries like South Korea that were more successful in containing the outbreak. Scientists now estimate that for every confirmed COVID-19 case, there are likely five to 10 additional individuals in the community unknowingly infected. This is why social distancing is not just for the elderly and vulnerable. Young and healthy people may be unknowingly carrying the virus and transmitting it to others. Research has shown acting fast on a collective scale to avoid exhausting hospital resources can reduce the number of deaths by a factor of ten. The message is clear: social distancing only works if we do it early and extensively, when things don’t seem that bad yet, to nip this virus in the bud before exponential growth really takes off.

Even if we accept all of the above , the question remains: How long exactly will we have to live like this? How long will we be without baseball? Nobody knows for certain, but as of right now, outcomes range from a Memorial Day Opening Day in the most optimistic scenario to no baseball at all in 2020 in a pessimistic scenario. One high-ranking club official told Bob Klapisch that, “an abbreviated spring training in late May, followed by Opening Day in early June” is a possibility.

Before 1961, the standard season was 154 games, and the work stoppages of 1995, 1994, and 1981 reduced those seasons to 144 games, 112-117 games, and 103-111 games, respectively. In 1995, the closest analogue to this spring’s timeline, reconvened teams played a two-week long second spring training and MLB allowed for 28-man rosters to start the year. The longer the shutdown lasts, however, the longer the second ramp up period must be. The league is motivated to get as many games in as it can, and executives are prepared to consider playing the regular season into the late fall and early winter, but it’s clear the choice could be out of the league’s hands.

“You’re going to potentially be in warm weather spots or domed situations,” said Yankees manager Aaron Boone to ESPN’s Marly Rivera. In other words, games could be played at neutral sites. We’re in this for the long haul—to paraphrase Yogi Berra, it won’t be over even when it’s over; even if baseball does return in 2020, it’s going to be very different from what we’re used to

“I think this idea … that if you close the schools and shut the restaurants for a couple of weeks, you solve the problem and get back to normal life—that’s not what’s going to happen,” said Adam Kucharski, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, to Vox. “The main message that isn’t getting across to a lot of people is just how long we might be in this for.”

A new report from the COVID-19 Response Team at the Imperial College of London says suppression of this pandemic requires social distancing to be maintained “until a vaccine becomes available (potentially 18 months or more).” This certainly seems grim for baseball in 2020—at least baseball as we know it. The reason for this is the countless untested individuals walking around, unknowingly infected. If we implement extreme social distancing for a couple of weeks and then simply lift all restrictions and let people gather in large groups again, that could cause another outbreak. Even if we are able to slow its spread, the virus will be lingering in the population for up to two years. We won’t necessarily need to stay in complete lockdown for 18 months, but we’ll need to take things slow even after the number of new cases begins to decline.

“Once things get better, we will have to take a step-wise approach toward letting up on these measures and see how things go to prevent things from getting worse again,” said Krutika Kuppalli of the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security to Vox. For baseball, this may mean playing games without fans for a while even after the season does return, a possibility MLB and fans have to be prepared for.

In the meantime, what are we to do when our choice of escapism has been snatched from us, arguably when we need it most? We all like a good Netflix binge, but if the readers of this article are anything like me—and I suspect they are or they wouldn’t be here—it’s a poor substitute for the cadence of a 162-game season.

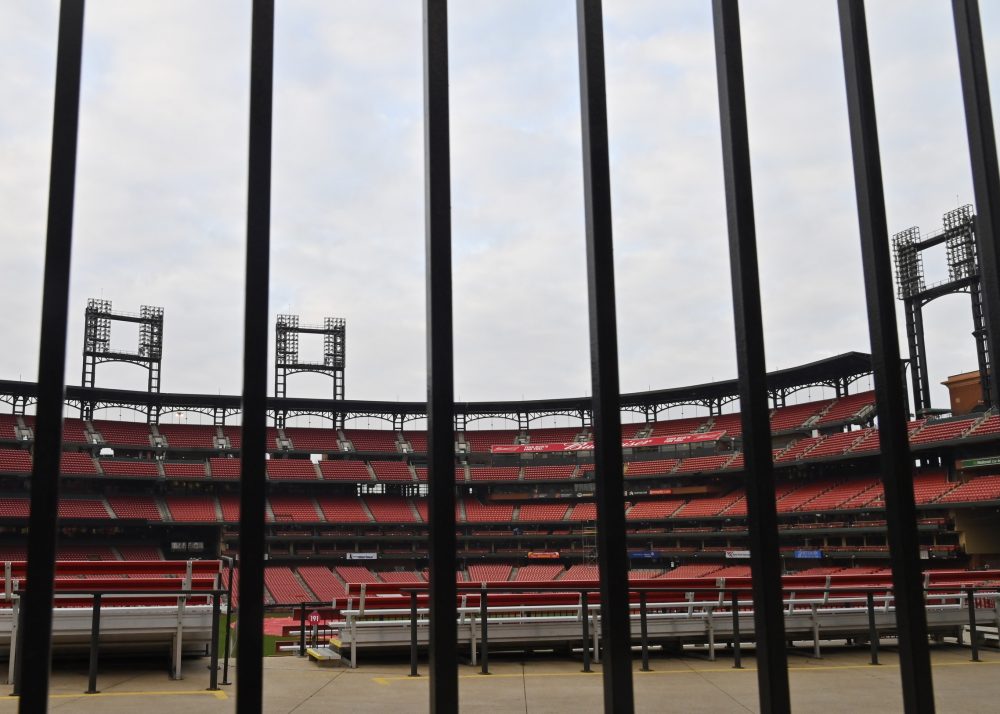

This isn’t entirely unprecedented, although the exact cause of the delay of the season is novel. Baseball has been forced to press the pause button before for labor stoppages and for other national emergencies. But each time in the last century the world seemed to halt on its axis, baseball helped pantomime normalcy. The sport enjoyed record popularity after World War II. We emerged from the dark and blinked our eyes in the face of Mike Piazza’s home run on September 21, 2001. The pain of a city in crisis echoed in the seats of an empty stadium on April 29, 2015. Times like these remind us that sports are a reflection of life.

Social distancing doesn’t mean we are alone, even if we are isolated physically. In fact, togetherness and community are more important than ever. Minor leaguers are helping each other raise money to get through this. Teams have pledged $30 million to ballpark employees. Our online communities will be here, writing about baseball, talking about baseball, and tweeting about baseball, keeping the seat warm until America’s pastime returns.

Allison McCague has her PhD in Human Genetics from The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. She is currently serving as a Rutgers University Eagleton Science and Politics Fellow with the New Jersey Department of Health.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now