This article was originally published on July 16.

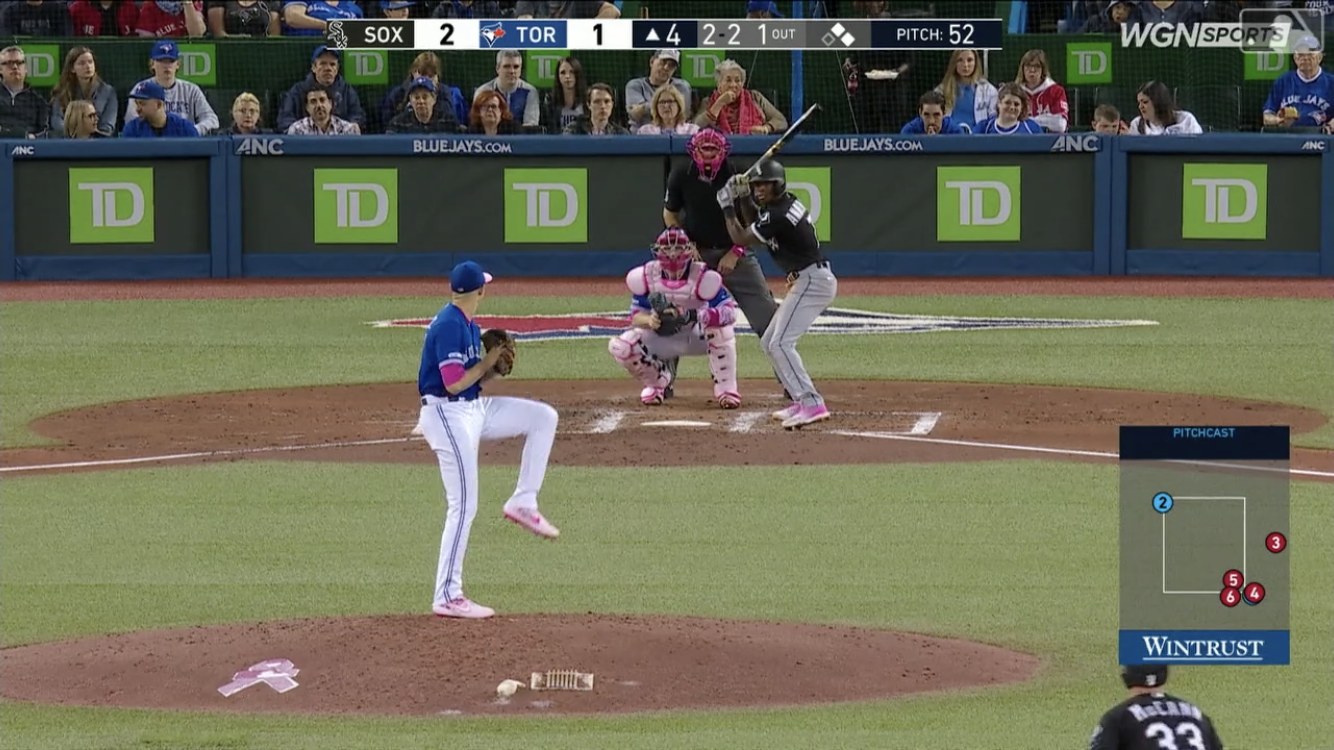

It was clearest, probably, on Mother’s Day of 2019 in Toronto. The White Sox were visiting the Blue Jays, and facing tough sinkerballer Aaron Sanchez. Tim Anderson wore pink-highlighted cleats as he stepped into the batter’s box. Between the brilliant color of the shoes and the artificial neatness of the dirt and chalk of an artificial field, it was unusually easy to see what was happening. As Anderson dug in, his front foot was well in front of home plate, even before he strode into his swing.

When he cut that swing loose on a lousy 2-2 sinker that instead floated, Anderson cranked a three-run homer to center field. It was his eighth bomb of the year, and he finished that day hitting .331/.362/.535. The rest of the way, despite a sprained ankle and his power surge slowing to a trickle, Anderson would hit .337/.355/.497. His start was impressive, but given his extremely aggressive approach and a profile that requires him to run a high BABIP in order to thrive, the way he sustained his production over the course of the long season is especially exciting.

Speaking of BABIP, Anderson finished the season with a near-historic .399 in that category. That makes him a candidate for heavy regression in the eyes of some but before we chalk his breakout up to good luck, let’s take a closer look at the way he was set up in the box on that home run in Canada 14 months ago.

An MLB batter’s box is six feet long, from front to back, with home plate centered in that span. In bygone eras, players varied not only in how close to the plate they stood, but in how far forward or backward they were in the box. Some hitters would also move up or back in the box based on the velocity and style of the pitcher they were facing. These days, though, that variability is virtually gone. Pitchers throw so much harder than they used to throw that setting up anywhere but the very back line of the box seems as counterproductive and antiquated as a sacrifice bunt from a No. 2 hitter.

There might be a few other hitters in baseball who don’t pin their back foot to the chalk at the back of the box, but arguably none are as notable as Anderson. Nor is this something he has always done. In fact, he only began to move up in the box late in 2018. As you can see, though, he’s become fully committed to that starting point. He edges forward a bit in two-strike counts (like the one he faced against Sanchez), and he edges backward a bit when facing certain pitchers. But throughout 2019, he frequently set up a foot or more in front of the back line of the box.

Anderson talked to Jared Wyllys last fall about the fact that he hit from a more upright stance in 2019 on the advice of assistant hitting coach Greg Sparks. He felt it gave him better plate coverage. He put in a lot of swings during the offseason ahead of 2019 to get comfortable with the new stance, and the result was a new swing, too. His hands stayed closer to his body during the early phase of his swing in 2019, giving him more bat control and a quicker path into the hitting zone.

Between his exceptional natural bat speed and those adjustments, Anderson gained the ability to make hard contact more consistently, which is exactly what happened in 2019. However, in order to take off the way he did, he needed to do more than raise his average exit velocity. In his first three seasons in the majors, Anderson pulled 43.3 percent of his batted balls. In 2019, that number plummeted to 32.7 percent. For the first time, he pulled fewer than half of his ground balls.

Hitting to all fields matters, even for a fast right-handed hitter. The shift wasn’t ever likely to swallow Anderson’s production whole, but the ability to drive the ball to all fields both robs the defense of the ability to shift effectively and signifies a general feel for hitting that will show up in every other aspect of process and production. Anderson’s old swing, combined with his bat speed, allowed him to out and around the ball far too often, and he pulled too many balls weakly to the left side. Getting more upright and using a more compact (but no less powerful) swing was valuable.

By moving forward, Anderson could make himself later on the pitches on which he used to be too early, even as he eliminated wasted motion from his swing and achieved a more direct path to the ball. He could change the angle of his bat at contact while maintaining a contact point well in front of home plate. Going the other way is, in some measure, a matter of getting the timing and angles right, and sometimes it’s hard to do those things from the back of the batter’s box.

His comment in the 2020 BP Annual alludes to “material improvements in contact rate and Anderson’s ability to stay with and drive breaking pitches,” and the latter phenomenon can be chalked up partially to the move, too. It’s (marginally) easier to hit a breaking ball when you steal an extra foot from its flight, and (not-so-marginally) easier to stay back on such a pitch and drive it when you steal an extra foot’s worth of time from yourself, thereby lessening the likelihood of being out in front of it.

This approach wouldn’t work for most players; that’s why it’s so much fun to watch it work for Anderson. It allows him to weaponize his aesthetically pleasing style, rather than try to conform to a more traditional, patient approach. It also nicely summarizes what makes Anderson special in all facets of the game: He’s a go-getter. He’s literally going to go get the ball, or the next base, at every opportunity, and that shows up even in the way he steps to the plate. His pre-pitch motions include an almost nervous repeated lift of his front foot, keeping his weight back but his whole body ready to leap into action, his stride in progress before the pitcher has even taken his sign. That he would set up that way, and do so from a foot closer to the pitcher than almost any other player in the league, tells you what Anderson’s thinking when he goes to bat. He’s not waiting to be given anything. He can’t wait to go get it.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now