Every Tuesday and Thursday, Too Far From Town shines a light on the 42 (really 43) minor league baseball teams in danger of losing their major league baseball affiliations, effectively leaving them for dead. Today we focus on the Bristol Pirates, a Rookie Advanced affiliate of the Pittsburgh Pirates. You could take in the previous installments here.

We are going to cheat a little bit on this one. Of course we could have a good infotaining time looking back at the Bristol Tigers (1969-1994). 26-year-old Jim Leyland’s first professional managerial job was with those Tigers, in 1971. Jim Leyland was fewer than 50 years old once? We couldn’t believe it either! Leyland tried and very much failed to hide his smoking from his charges. At the end of the year the team — they finished 31-35 — presented him with a wristwatch. He seemed well liked. It’s a nice story. That would have been cute to revisit.

Mark “The Bird” Fidrych got his nickname while pitching for Bristol after his teammates noticed he resembled Big Bird. That’s a nice story but *turns story upside down, shakes it, closes one eye for some reason and examines more closely* that is the entirety of it.

A two-time Super Bowl champion played for the Bristol Tigers in 1981. He was a quarterback for the Denver Broncos! Oh darn, it was Bubby Brister, not the former Yankee prospect.

We could talk about how Bristol is in both Virginia and Tennessee, but we covered this kind of thing the other day with Bluefield, and the ballpark and parking lot are both in Virginia, so we don’t have to hit you with 16 tons of state chicanery and have to change our name from Tennessee Ernie Ford to Virginia Virgil this time around. We know what we’d get.

Lou Whitaker started his professional career as a Bristol Tiger! He struggled at baseball for the first time in his life there. He made three errors in a game and cried afterwards. It all worked out. We all know that. What, you want us to focus on how a young man cried once? What’s wrong with you?

There’s got to be a story behind the First Mate’s Club, but sign-ups are currently closed and it is just too sad to explore.

There’s a better story out there.

The Bristol Tigers became the Bristol White Sox in 1995, and spent almost two more decades affiliated with an American League team before Bristol became a Pirates affiliate in 2014. It was a return to its roots — the Class D Bristol Twins of the Appalachian League was a Pirates affiliate during the 1952 and 1953 seasons. The Bristol Pirates currently play in the Appy League too. And it’s the same Bristol. And since 1999, there is a plaque commemorating something a Bristol pitcher did on May 13th, 1952 at DeVault Stadium, the current home of the Pirates. It was something nobody had ever done in a professional nine-inning game before, and something nobody has done since.

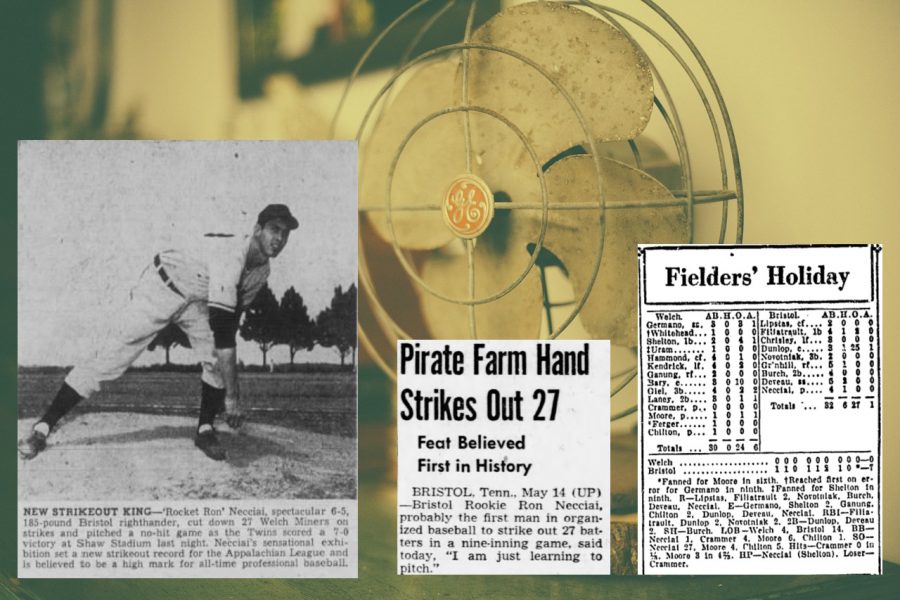

Nineteen-year-old right-handed pitcher “Rocket” Ron Necciai didn’t throw a 27-strikeout perfect game, because baseball might cease to exist if someone in the professional ranks ever threw a 27-strikeout perfect game. Necciai (pronounced Netch-eye ) tossed a 27-strikeout, nine-inning no-no. It’s still a record. (And singled to center in the 2nd inning!)

Necciai was a pitcher in high school until one of his fastballs broke a batter’s ribs. His coach made him promise to never throw that hard again. Necciai signed with the Pirates as a first baseman (after the team’s barber discovered him), but he foolishly threw the ball impressively well around the diamond, well enough that his manager George Detore, sure fine, deto(u)re-d the Rocket’s career right on back to hurling from the bump. He walked pretty much everybody at first, and quit the game to work in a steel mill near his Pittsburgh home. Detore steered him back to baseball by providing him a side hustle as the team’s bus driver, netting him an extra 90 bucks a month. Necciai continued to pitch poorly, so Detore one day challenged him to throw harder. Rocket mentioned the kid and those ribs. Detore didn’t care about some dumb kid and his stupid ribs. Necciai threw hard again. He succeeded for the first time in Class D, then stunk again in Double-A. In the fall of 1951, Branch Rickey, then finishing up his first year as general manager of the Pirates, saw Necciai pitch at the team’s school for top prospects. “He had all the raw ability any pitcher ever had,” Rickey said. Since Rickey tended to know what he was talking about, Necciai was invited to major league camp in 1952, set to start the season with Pittsburgh in fact, when he complained of ulcers. He couldn’t eat or sleep. The team physician prescribed Banthine pills and a diet of melba toast and cottage cheese — any vegetables had to be strained. No fried food, nor dry cereal. Since he was now a 6’5”, under 150 pound stalk of nothing, Rocket was in no shape for the Pirates. If he had to pitch for any of Pittsburgh’s minor league teams, Necciai reasoned, it had to be whichever one was skippered by Detore.

On Bristol’s Opening Night at Shaw Stadium (now a dairy plant), Necciai struck out 20 batters. He struck out 19 in his next start. Then in a relief appearance, he fanned 11 of 12 batters. He did all of this while still dealing with stomach issues. On a damp Tuesday evening, May 13th if you want to get specific, Ron Necciai wasn’t sure if he’d be able to make his scheduled start against the Welch Miners, the Boston Braves affiliate that would win their first of back-to-back Appalachian League titles that season. Warming up in the Shaw Stadium bullpen, Necciai felt he had nothing. He told bullpen catcher Don Becker he did not think he would be able to finish the game. He felt a “burning sensation in his stomach”, according to Pat Jordan’s 1987 Sports Illustrated piece about Necciai and that evening. He toughed it out and started in front of 1,183 unknowingly lucky human beings.

All three Miners that came up to bat in the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 6th, 8th innings struck out. Three Miners struck out in the 3rd and 7th innings too, but Joe Giel in the 3rd reached first on Don Deveau error at short, and in the 7th Necciai walked Bob Ganung. Only two hitters whiffed in the 4th inning, where Necciai plunked Mickey Shelton and allowed Ganung to ground out to first.

After the third inning, Necciai told his skipper his stomach was burning. Choo-Choo the batboy was dispatched to go to the clubhouse and give Necciai milk and cottage cheese. Choo-Choo’s night was not done: apparently Choo-Choo was later sent to the mound — in Jordan’s account it was while Rocket was pitching at some point during the final three innings – with a glass of milk and a Banthine pill for Necciai to choke down.

The fans were aware something was special was going on, or at least that Necciai was dominating and the Welch Miners looked like fools. The Bristol Herald Courier recounted the prop comedy the next day:

Members of the left field bleachers “association” presented Manager Jack Crosswhite of the Miners with a large paddle, with a hole in the big end, during the seventh inning. C.C. White made the presentation on behalf of the “association.”

Rocket Ron had 23 strikeouts entering the 9th inning. The first batter struck out looking, but not before he popped up in foul territory near home plate and catcher Harry Dunlop listened to the screaming fans who insisted he let it drop. The second batter struck out swinging. Bobby Hammond struck out swinging at a curveball, but Dunlop couldn’t handle it cleanly, and Hammond reached on the error. Dunlop swore ever since his error was not on purpose, but conveniently, Ron Necciai had the chance to strike out a 27th batter, and he did, with Bob Kendrick as his historic final victim.

Necciai got the call to the majors later that season. He went 1-7 with a 7.08 ERA. Then the Army drafted him. He lost 25 pounds in 65 days, mostly spent in a Fort Knox hospital. After he received a medical discharge, he tried to return to baseball but quickly developed shoulder pain. Eventually a Johns Hopkins doctor let him down not so gently, telling him: “Let me put it this way, son: Why don’t you go home and get a job in a gas station?” The ulcers stopped with his baseball career. He became a part-owner of an equipment distributorship (not a gas station). One day he was told he had a torn rotator cuff. He was 70 years old.

Before the plaque ceremony in 1999, Ron Necciai remembered the moments right after he made baseball history in Bristol, Virginia. He did not realize he had struck out 27 batters. And once he was made aware of that fact, he was not impressed with himself.

Me being a smart mouth, I said, ‘Oh, so what. They’ve been playing this game for 100 years. Somebody has done it.’

Art (Pirates portrait): Sarah R. Ingber

Music (“Bristol Blues”): Davy Andrews

Music (“Who’s the Pirate Now?”): Roger Cormier

Prose: Roger Cormier

Photo (Ron Necciai strikes out 27 press clippings, left to right): Bristol Herald Courier May 14, 1952, The Pittsburgh Press May 14, 1952, The Sporting News May 21, 1952

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now