Editor’s Note: Thank you.

This is not what you dreamt of, tossing a soft baseball in the backyard to a daughter who swings and misses, swings and misses, while the other daughter, who is supposed to be running the makeshift bases and shagging balls, stops to put on a show from the swingset, thoroughly uninterested in the proceedings. The sky is a buttery orange against the dark trees of evening as the sun sets somewhere you can’t see. Your wife has the camera, and the picture will turn out too dark and oddly cropped, the familiar foliage of the yard a menacing wave in the background.

It’s just your arms in the frame, sinewed still from years of rowing crew, catching passes and pitching baseballs. Real pitching, not what you’re doing here, underhanding to a blonde-banged and slip-on-shoed daughter who swings and misses every time. You correct her stance, try to get the chaos of her lower half orbiting the same planet her arms are on; you try to keep her from falling to one knee as she swings. She says okay, dad, okay, I get it, and swings and misses, and falls to both knees. You surrender the idea of her becoming the starting pitcher for the University of Washington’s softball team. She is left off the roster for the All-CYO basketball tournament, because she is as poor at shooting a basketball as she is hitting a baseball, and she cries. You suggest she might row crew like you did because she, too, has a broad, strong back, and she does not find this to be a compliment. Finally, when she is placed for a third consecutive year on the freshman volleyball team, you give up the last remaining shreds of the idea that she is made in your own image.

Her interests grow less interesting to you. She is obscured behind a book, under headphones, behind a stage curtain. You are in the dark now, or she is, past a sunset you can’t see, among the menacing shapes of the backyard. Once when helping her fix her car, a temperamental roller skate of a thing she inherited from her grandmother, she twists too hard and breaks off a piece in the engine compartment, a small, inconsequential piece, but you laugh and say “not so rough, Gorgo,” which was your nickname in college, when you were strong and rowed hundreds of miles a year, and she cries and storms off, and later you get yelled at.

And still, all the time, you ask to go have a catch, during holiday dinners and summer breaks, and then one day she says yes; the backyard is overgrown now and too small anyway so you drive down the street to the park and you run through the grass like a dog unclipped from its leash, ready to shag pop flies; you could catch anything, you have that much energy stored from years of ballet recitals and musical theatre performances and sitting still in the dark.

Over the years the yeses become more frequent but your body, that reliable companion, starts to say no; you keep your foot to the floor but the car just won’t go like it used to. There are other, smaller nos: you leave the milk out one too many times and a sign goes up on the fridge; you go to the carwash and forget your wallet; words become slippery fish, hard to grasp at as they flash through your mind, the clear river of which is now spotted with dark patches, things you used to know but don’t anymore, cannot get back to. The park is too much now so you return to the backyard, where she is underhanding pitches to you, gentle tosses that somehow find your mitt each time. You switch to a softball, a sunny orange that’s easy for her to dig out when your throws go wayward, which they do more now, into that unknowable black stretch of the backyard, the dark bushes there, a wave you can’t stop from cresting, until she emerges from the blackness, bright ball held aloft, calling it’s okay, Dad, I got it.

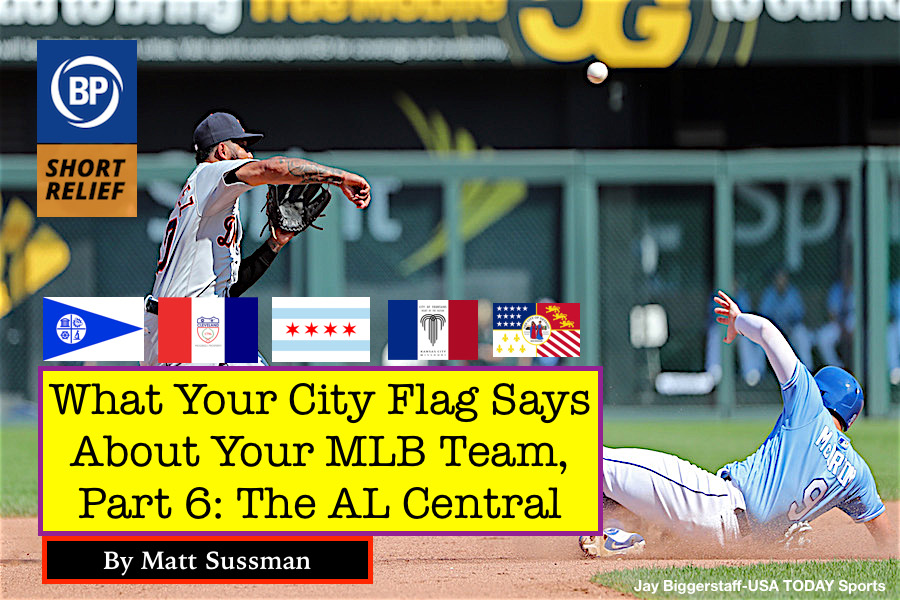

We’re finishing last with the AL Central, and something feels very comfortable about that. Hope you enjoy French history, for some reason.

Kansas City

First rule of vexillology: always start with France’s flag. Then take a page from your seventh grade writing teacher and “write what you know.” City of fountains. Heart of the nation. Won a World Series with that one team that one time and everyone tried to copy it and it didn’t work. The only graphic part shows that it’s trying to be two things at once: a good baseball team, and a baseball team that brings Alex Gordon, again.

Cleveland

How does one show that you’re adverse to Kansas City? Just flip their flag horizontally, then try the bare minimum. Include the skeleton of an interstate marker and some local motifs that are not guitars, because they are so much more than the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, just ask them. And for good measure, include the attendance of an August home game. Just looking at this somehow make you hear that drum guy.

Chicago

Wait, I thought we already did the Cubs. That’s odd. Seeing as how that’s their city’s lone team, let’s move on.

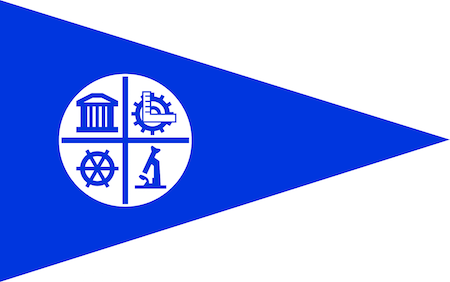

Minneapolis/St. Paul

Do we treat the Twinned Cities as a whole or in separate flags? Because both of them scream nerdship: Minneapolis’ was repurposed from a high school science competition, whereas Saint Paul’s just looks like a robot sneezing. Put them together and you have a technologically advanced team that said “it snows a lot up here, and while we play indoors, we’d very much rather not.”

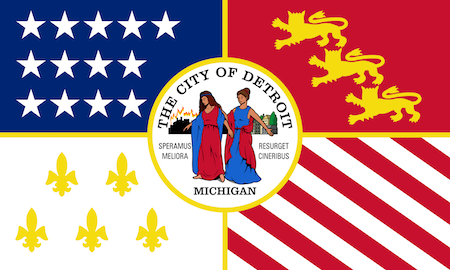

Detroit

Stars make up only a quarter of the team and it’s not enough. “Speramus meliora resurget cineribus” literally means “we hope for better things, it will rise from the ashes,” and there’s not even a joke for this one. The two women in the middle are playing some type of internet game, like “1 corner gotta go” or “choose a corner to defend you, the rest are trying to kill you” when looking behind them they should probably be calling the fire department. But in terms of cohesion, this is the type of flag you put out there that guarantees you yet another No. 1 draft pick.

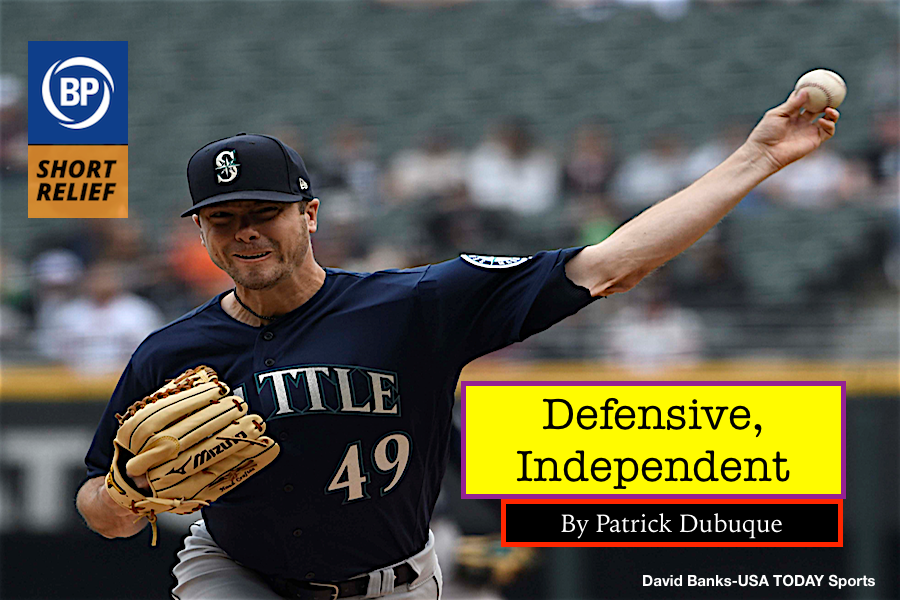

The best thing about baseball is that it’s unfair. Everything in life is unfair, a crosshatch spiderweb of systems and patterns that affix and support each other, twisting and corrupting. Redlining and white flight, intentional or unintentional, it’s all the same: Every rule and value created for the sake of equity gets manipulated for private gain. And afterward, always, the smirking realists arrive, voices clear, teeth gleaming, to tell you that life has never been fair, or worse, to tell you that it can’t be fair because it wasn’t fair before, that making things fair would be unfair. They smirk because they understand the world’s greatest truth: That everything is terrible, and hopeless, and comfortingly unquestionable. They are not proud of their scars. They are their scars.

What makes baseball beautiful is that its unfairness lies exposed. The bad call, the bad hop, the pop of the elbow, the deciding play witnessed from the on-deck circle: these are all sad endings we’ve grown to accept, at least in the game, if not in life. From high above the forty thousand witnesses, one figure in the booth casts their judgment, E-4, and it becomes shared history. They can’t be denied, or obfuscated, or justified. Sometimes there’s nothing you can do.

Sabermetrics have dealt two blows to the idea of baseball as symbol for the bootstrap-powered parade of American heroism. The first, in the 80s, was the slow realization that clutch hitting was a myth, and that a thousand narratives of greatness were well-meaning folk remedies. The second, perhaps more damning one, arrived on this site in the form of DIPS, dismissing the idea that pitchers could control the number of hits allowed on balls in play, that the fires of heaven smote cowards with sun doubles. Each truth further frayed the manifest destiny of winning, that only the losers deserve to have lost.

The game is written like a story, if just for a moment. All of baseball exists as an idea in the pitcher’s head, and what we see is all causation and chaos theory. The pitcher is in control until the moment the ball leaves his fingertips, and then, almost always, he is a spectator like the rest of us, witnessing in awe or horror. Hitters react. They snap their wrists. They run in lines. They perform. Only the pitcher can look ahead, decide the success in their future, and either meet or fall short of it.

We spend our lives pitching, and often it takes months, or years, for the ball to cross the plate. It almost doesn’t matter what happens at that point, when the swing of the bat snaps our necks upward like a noose. It felt good when it left my hand, you tell yourself. That’s all that matters.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now