Though I am not named Larry, nor have a brother Harry, five days from now I am going to marry. Regardless of whether or not you can make it, none of you are invited to the ceremony. I don’t mean to be rude about that. It’s just that we don’t know each other, and this is a ridiculously small ceremony.

My first wedding was bigger. Of course it was. We would be together forever and we demanded attention be paid to our eternal love. It was all very demonstrative. In 2004, I gathered family from across the country, close family friends who, for some reason, wanted to travel to central Pennsylvania, and friends of mine from high school, college, and grad school. They numbered in the hundreds. The wedding party consisted of two best men, a maid and matron of honor, two groomsmen, and two bridesmaids. There was a ring bearer and a flower girl. It happened in a large Catholic church and the reception in a country club none of us belonged to. I still don’t know how much it cost.

I remember surprisingly little from that day. My dad telling me I didn’t have to go through with it. My bride pulling out a blue handkerchief from her bustier during the ceremony to wipe away tears. The fact that I didn’t get to finish my salmon before we had to go visit each of the tables, and then my food was taken away. There was a vase full of scotch at one point. My brother got rip-roaringly drunk with a former babysitter at the open bar. Afterward, my bride and I retired to a hotel where we collapsed from exhaustion and did not consummate our marriage.

I was younger and dumber then. My latest bride (let’s all agree never to tell her I called her that) and I have more realistic plans and expectations. The ceremony and reception will be in the same room at a local distillery, saving us all both time and effort. Only immediate family is invited — fewer than 20 total people. We have limited the attendees to two free drinks each. The day’s agenda has been amended to allow for a nap. Then we will meet friends at a second location for a revelrous afterparty.

I bring this up here in this space because I attended Saturday’s Twins-Tigers tilt at Target Field with BP superstar Matthew Trueblood, who pointed out how teams have begun to shift Twins infielder Luis Arraez to take away as many of his soft liners to left-center as possible. It’s possibly one reason he’s only hit .279 in his last 102 plate appearances. The scouting report has seemingly gotten around.

This is not a new phenomenon. A new prospect shows up on the scene and starts peppering the ball all over the outfield. Or he fools honest-to-God big league hitters with mediocre stuff off the plate and a deceptive motion. But that scouting report catches up to him, and guys like Arraez can start to seem like disappointments.

It’s just that, in the beforetime, you had much more time to celebrate their rise before the fall began. With the data available to clubs now, that shift is starting sooner and sooner. The bloom is still on the rose as opponents begin to pluck it and players have to start making adjustments earlier.

The second time around, everyone has learned something. They are more realistic, and design a path forward that better reflects who that player is and will be. And, if all goes right, we find that the weakness was in the initial unsustainable process, rather than in the player himself. God, I hope so.

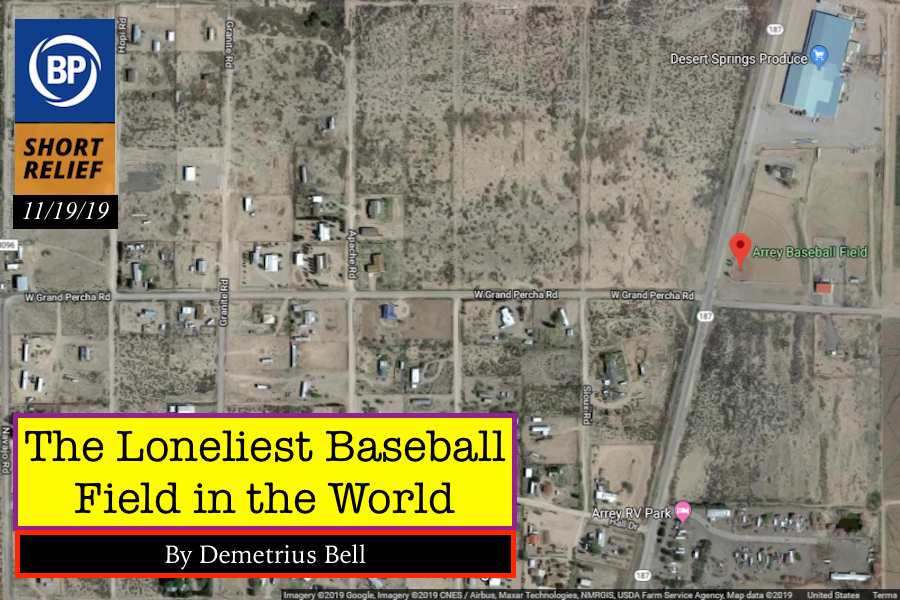

On the northwestern corner of an intersection where New Mexico State Road 187 splits West Grand Percha Road into East Grand Percha road, there is what appears to be what’s left of a baseball field. This skeleton of a baseball field is located on the Northwest side of a town in New Mexico known as Arrey. Arrey is a bit south from Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, which is a town that’s only famous for its name and being the fictional hometown of one of the most infamous professional wrestlers to ever walk the face of the Earth.

The 2010 U.S. census says that Arrey’s population is at 232, and apparently that was enough to get enough people in baseball uniforms and on the field in this tiny city. This little town in New Mexico may not have a lot of stuff to get into, but it had a diamond at one point and I can only imagine what that was like when it was actually functioning. It looks like if you were a kid growing up in that particular part of Arrey then you only had a couple of options when it came to having fun outdoors: You either kicked a can down the road until you ended up at Desert Springs Produce or you took a ball and a bat over to the diamond and started peppering balls around.

In the interest of transparency, I enjoy just messing around on Google Maps and I enjoy getting lost from time to time using the Street View feature. It’s a wonderful way to eat up any amount of time ranging from a couple of minutes to a few hours, and it’s also the world’s cheapest vacation if your imagination is strong enough. However, on this occasion I had a mission where I was looking for what appeared to be the most desolate place where you could find a baseball diamond in the good old USA. I think that this particular ballpark in Arrey, New Mexico fits the bill.

To paraphrase a line from Rust Cohle, the baseball field in Arrey is like someone’s memory of a baseball field. I wonder if there was a time where it actually had green grass and there were actually seats behind home plate or separately placed on each side of the diamond. Either way, there’s nothing to fall back on since I don’t think that anybody really liked the place enough to take photos of it while it was in whatever prime it had. All we have to go on is a review that declares that Arrey Baseball Field was a ”good place.” We’ll just have to take your word on that one, dude.

While I am well known as that person among my friends who has definitely not seen whatever show everyone else has been talking about for months, I have seen Good Omens, the Amazon Prime adaptation of the 1990 Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett novel of the same name. Both of these texts are quintessentially British things (a significant factor toward my enjoyment, along with cleverness and very good acting well peppered with witty repartee). Good Omens is also about averting the Apocalypse, and not in any kind of metaphorical fashion; an angel and a demon who’ve been on Earth since the beginning take it upon themselves to avert the end times, as precipitated by the 11th birthday of the Antichrist. Through a series of unexpected events, the Antichrist grows up in a perfectly mundane household in the sleepy village of Tadfield instead of being swapped for the child of the American ambassador (played to boorish perfection by Nick Offerman). And it’s at this moment that Good Omens, a show in which biscuits, ice lollies, and tea factor heavily, becomes a baseball show.

In greeting his newborn son, the ambassador says, “A boy! Mr. President, I have the honor, sir, to report myself the father of a regular Y-chromosome son…a male, boy son…I’m going to teach him to play baseball, and on Sundays, we’ll go fishing…”

It’s notable that this welcome to the world takes place via a tablet screen; the American ambassador is with the President instead of being present at the birth of his child, and the President calls him away from even that much attention, even before he can finish the sentence.

The implication: it’s not enough to be male (with regard to XY chromosomes and the physical accouterments expected to accompany said chromosomes); one must also be a boy, which is to say masculine in behavior, in hobbies, in accordance with a very narrow script of what both masculinity and Americanness are. And boys play baseball.

Because the show is a comedy, the ludicrousness dial is obviously cranked to eleven, but it’s an equation most of us are familiar with. As last week demonstrated, through so many testimonies to the presence of women in baseball, not to mention the many people who identify outside of the gender binary who love the game, who play it, who are shaping it, some of us are a little tired of that equation. Not tired of boys and men playing baseball, but tired of the suggestion that only boys and men play baseball. Tired of the suggestion that there’s only one way to see the sport, only one way to be in it.

Last week also brought the world the delightful highlight reel of Ashlynn, who’s also pretty tired of people thinking this way.

Good Omens does not come back to baseball, but the shorthand of the ambassador’s monologue—a certain kind of rigidity that, when paired with the combined privilege and absenteeism the ambassador’s character exudes, could indeed lead to disaster—is a warning. It’s hyperbolic (the extremity is built into the show’s concept – apocalypse! angels! demons! the M25 on fire!) and I’m definitely turning the screws on the script here, but the question of who is permitted entry into the kingdom of baseball is always on my mind. I wish it wasn’t. I’m thinking so hard of what is an aptly written, actually very funny characterizing moment in a show that has brought me incredible joy because baseball also brings me incredible joy, except for the times when it doesn’t. Except for the times the sport and its ambassadors seem more intent on slamming the gates closed than holding them open.

More Ashlynns. More joy. That would be, as a particularly English angel might say, tickety-boo.

Photo of Karla Espinoza from Women’s Sports School.

This past week I had the opportunity to attend a scouting school for women in Arizona. We spent our mornings in the classroom, learning scouting terminology, hearing from guest speakers, and sharing stories from our experiences in baseball. In the evenings we went to games and practiced scouting, conspicuous in our purple polo shirts, filling up the scouting section. The men who usually sit in that section didn’t quite know what to do with us; some were solicitous, offering advice, encouragement, their business cards. Others moved seats and sniggered. Most asked who we were with and seemed relieved when we pointed to the male scouting director sitting back a few rows, like we were Victorian ladies in need of a sponsor.

No matter what the response, one thing was unchanging: we were there. We sat in that section I’ve always viewed as bounded with invisible cordons and we took up space. We took up space with our ponytails, our higher-pitched voices, our skirts and our laughs, our purple clipboards. We made that space conform around us. This is what you have to do when spaces aren’t built for you, and there are few if any spaces built for women in baseball; go in there, insist on yourself, and take up space. It was exciting, and empowering, and I left the ballpark every night full of hope and believing there was a space in baseball for me.

School ended on Monday morning, and my flight wasn’t until Tuesday. That night I returned to the ballpark, purple clipboard in hand, and endeavored to take up space again. But without my cohort, I wasn’t part of a wave to be noticed and contextualized, but an annoyance, an anomaly. My questions were answered with terse one-liners, if at all. I was reminded of what one of our guest speakers said to us, baseball’s lone full-time female scout, how her presence was called “fucking embarrassing” by an old-time scout. These scouts weren’t, on average, the old, grizzled type with mussed hair and ill-fitting khakis trailing over scuffed sneakers; they were young, with gelled hair, sharply-dressed in tapered pants and shined shoes, carrying tablets instead of stopwatches and notebooks. They wouldn’t be out of place in a boardroom, a finance conference, Seattle’s South Lake Union district.

As the news about Brandon Taubman’s harassment of a group of female reporters and the Astros’ subsequent denial of the story, broke over Twitter, I looked around at the other scouts in the section, also checking their phones on the inning breaks. None looked perturbed. As my Slack chat filled with links to outraged tweets and my phone dinged with texts from fellow scout school attendees [the timing of this!], theirs remained silent, implacable. As my shoulders sunk, weighted with sadness, they remained confident, upright, as sure of their place in the world as they’ve always been, safe in the spaces they’ve always known as their own.

The Martian might be my favorite book. The story is simple and accessible, the prose is formulaic but effective, and the combination of nerd science and dry humor fits my interests perfectly. I can read it or listen to the audiobook or watch the movie an endless number of times without losing enjoyment. It doesn’t hurt that the audiobook and movie are both fantastic. But on my latest reread, I noticed something, and I can’t get it out of my head.

On Sol 11, our protagonist’s log entry is one sentence: “I wonder how the Cubs are doing.” Understandable. When you’re alone on an entire planet, the mind tends to wander, and he’s been out of contact with Earth for about a week. But on Sol 16, the log entry informs us that it’s Thanksgiving on Earth. (NASA’s psychology team deciding the Mars crew should prepare a Thanksgiving meal from scratch, rather than just eat more prepackaged rations, is how Watney has a stock of potatoes that he can plant and grow as crops.)

All of that is well and good, but look at those two numbers. A Martian day is roughly the same as an Earth day, so in the span of five days Mark Watney went from wondering about his baseball team to Thanksgiving. The conclusion is obvious: In the unspecified near future year that The Martian occurs, MLB’s schedule has shifted such that the Cubs are playing in late November. And no, it can’t be that they’re in the playoffs: when Watney gets in contact with Earth three months later they inform him that the Cubs finished in last place in the division.

So, in this world, the major leagues are playing regular-season baseball as late as November. What does that look like? Is there a Detroit Tigers/Texas Rangers Thanksgiving game, a la the NFL, where the winning team cuts into a turkey on the baseline? And what about the postseason? Are there World Series games on Christmas? Unless every team plays in a climate-controlled indoor stadium, there would have to be some games played in super-cold weather. Even a little bit of snow would give pitchers an extra element of deception, but they’d have to work extra-hard to grip the ball properly.

Or Andy Weir just needed a throwaway joke and didn’t think of the inconsistent dates. But I like my idea more.

I almost said it aloud. He’s gonna do it, I thought to myself instead. He’s gonna launch one. And when Fernando Rodney’s first pitch sat belt high and just out over the plate, I really thought I was about to be proven right. Alas, Alex Bregman held his bat, and despite my feeling that still, It’s coming, I held my tongue.

The next pitch, of course, was a shoe-topper that Bregman uppercut into the heavens, a grand slam to put the Astros up 8-1. I was right, he did it, but no one else would ever know.

During the obligatory camera cuts of the dugout and the crowd while Bregman rounded the bases, we were treated to a four-act play. Justin Verlander and Gerrit Cole as idle spectators; Verlander and Cole as anticipatory revelers; Verlander still reveling as Cole puts it together; and then Verlander screaming, presumably, “I TOLD YOU SO” while Cole shrivels and dies inside.

You see, Verlander, like me, must have called Bregman’s shot. But Verlander, unlike me, told someone else. And judging by Cole’s reaction, must’ve put some money on it too.

If there is any greater feeling than calling someone else’s shot, in whatever sport it may be, I have yet to encounter it. Doing so makes that accomplishment, created solely by the athlete at the pinnacle of their ability, yours as well. “I told you so,” you — a couch goblin with chip dust on your shirt and feeling of restless atrophy in your leg muscles — tell your fellow couch goblins. “I helped make this happen,” you imply. “It was me. Me, me, me. Praise me.”

The first time I encountered a second-hand shot calling was the 2015 ALCS between the Royals and the Blue Jays. My college roommate and I drove to Kansas City for a weekend of barbeque but picked up last minute tickets to Game 1 too. He’s not much of a baseball fan or sports fan at all really, but for some momentary hysteria, in the fourth inning, with Salvador Pérez at the plate, he decided to say: “Watch this.” The next pitch Salvy poked over the left-center wall. Dumbstruck, I stared at him as he cackled, jumping and yelling “I told you so.”

Two years later, at an innocuous midseason Cardinals’ game, he did it again. The circumstances of that called shot are lost to memory, but his reputation as the home run whisperer, the tater clairvoyant, the man with a third eye for dingers was cemented. The previous title-holder, Babe Ruth, only called one shot after all.

Because I kept my inclinations of Bregman’s potential to myself, no one can verify that I too called someone else’s shot. I will forever be Gerrit Cole, never feeling Verlander’s boundless joy. I will stay a couch goblin, destined to know of home runs only after they break the outfield wall’s liminal plane.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now