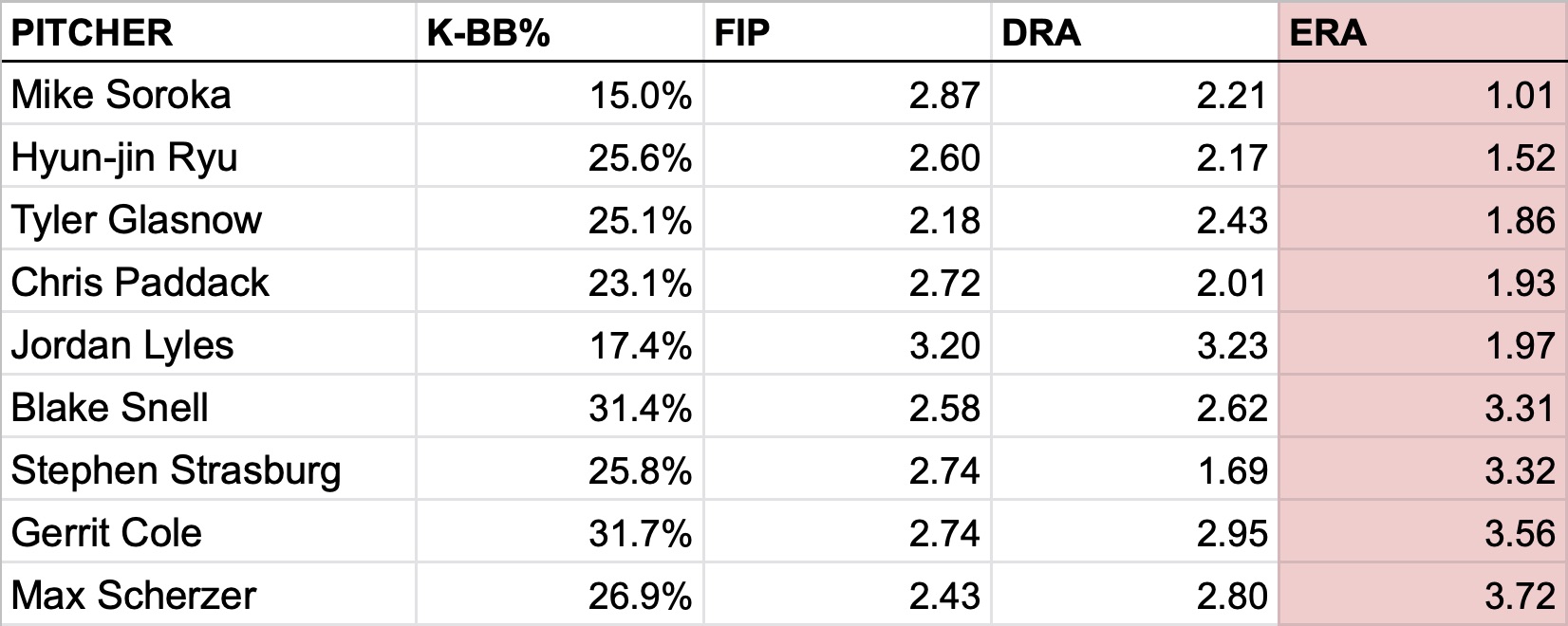

This is neither a test nor a trick, but it admittedly might feel that way. Below, there is a table containing the 2019 statistics for nine pitchers — all of them having quite good years. There are several leading indicators of ability and performance listed, and then there is ERA. The table is sorted by that tippy top totem of top-line stats.

See if you can discern any logical pattern for how the components fit together and spit out a certain level of run-prevention success.

There are a couple of stumpers, aren’t there? It’s not even Memorial Day, so there are understandably some wilder swings of fortune baked in, but Stephen Strasburg has the best DRA on the board — indeed, the best DRA in baseball — and an ERA that appears pedestrian compared to young Braves starter Mike Soroka or Pirates reclamation project Jordan Lyles.

Even if you love Soroka’s pitch-tunneling mastery and super-bendy sinker, his middling strikeout-minus-walk rate looks sketchy as punchouts and free passes comprise a larger and larger share of any given game’s events. And how is Astros star Gerrit Cole‘s elite performance in that category — tops in the majors so far — still managing to leak three or four runs per game?

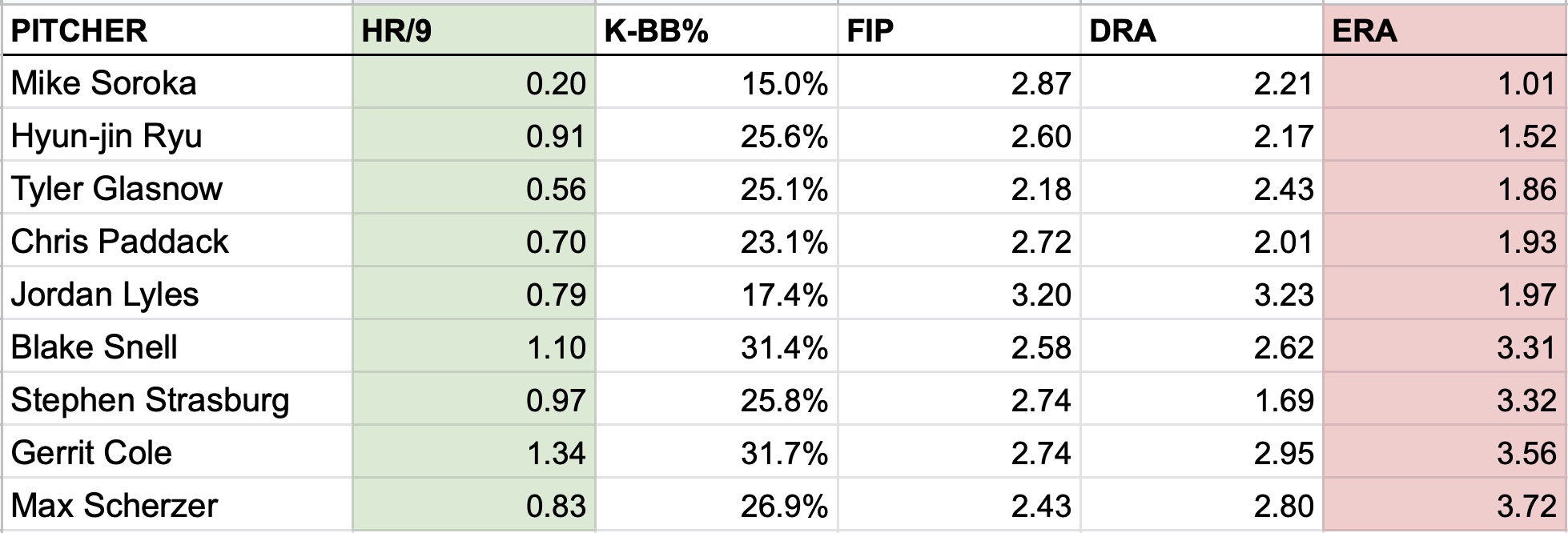

The missing piece of the equation, as you might have guessed, is home runs.

Preventing the long ball has never been a minor part of a pitcher’s path to success. A cyborg that struck out 50 percent of its opponents but allowed 2.5 homers per nine innings would still be, in strictly technical terms, screwed. Strikeout rate has become the bedrock of contemporary evaluations, though, because it has proven to be a more reliable skill. It can be developed and tracked without the universe’s whims throwing things too off kilter.

The same cannot be said for homer prevention. The average pitcher’s year-to-year ability to deter long balls isn’t much more predictable than a feather in a stiff breeze.

However, the current environment — in which more homers than ever are being hit overall and six teams are scoring more than half of their runs via homers — magnifies its significance to an almost absurd degree. The question is not whether outlier-ish launch-limitation artists can sustain their head-turning starts, but whether the basic nature of that number we see in the ERA column has changed.

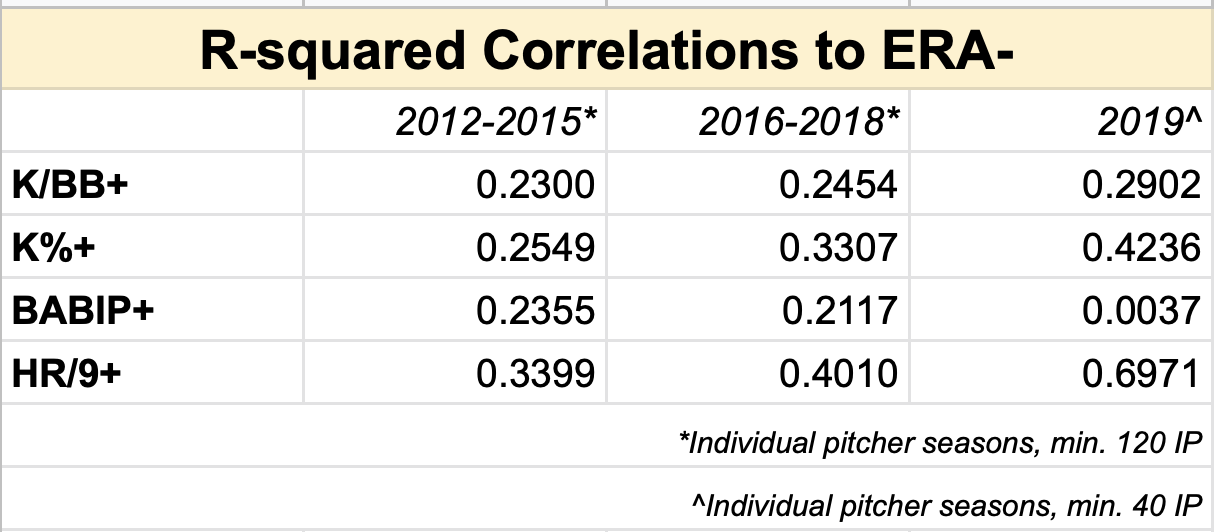

Let’s take a look at how some indexed (and thus era-adjusted) stats correlate to indexed ERA. This tells us, from 30,000 feet, how much variation in “who’s good this year?” appears to be explained by various parts of the performance. Most years, you’ll note, each stat comes with a weak correlation in the 0.3 range or lower (where 1 is a perfect line on a plot and 0 is no correlation, a scattered blob). This makes sense; the whole of a pitcher’s season is complicated.

In 2019, well, things are a bit skewed. Avoiding homers is now a powerful indicator of allowing runs in general. Not a shocking development, but with the caveat that smaller samples lend themselves to more extremes, this conveys a striking message: Do whatever you want on the mound, just don’t let the ball fly over the fence.

The hitting side of this equation has snowballed from a host of strategies and reactions, but the upshot is this: Major-league batters are now trained — hell, designed — to turn around one or two nasty Max Scherzer pitches for homers each game. Facing a less daring arm content to steer clear of the plate, they may well get to first base quite a bit without ever reaching home. They’re finely crafted machines gliding with advanced anti-missile protections, but also easily grounded by turbulence.

Of course, this doesn’t mean guys like Brewers soft-tosser Zach Davies will roll through the season with a sub-2.00 ERA. He entered Wednesday afternoon with a 1.54 ERA, having allowed 0.68 homers per nine innings across his first nine starts. Then the Reds ripped him for two homers and six runs in three innings. Because dinger limitation is just not always in the toolbox.

No, homers being this pivotal doesn’t lend anyone an advantage or set anyone else on a course to ruin, at least not in any logical, merit-based way. It mostly just means chaos. In keeping with the stampede toward the Three True Outcomes, strikeout rate is also becoming a better and better explainer of ERA variations. Over the course of the season, that should help the Scherzers and Coles of the world reach the pinnacles their talents would appear to deserve.

Then again, maybe not. We embrace randomness and chance in many areas of the sport — Wild Card games, leagues and divisions that are sometimes totally unbalanced, short series to determine champions. We are perhaps not used to the universe holding quite this much sway over who’s good and who isn’t.

At least until the ball changes on a dime again, or some other force shifts the state of play, we’ll have to linger even longer over those basic barometers of pitching success (and of course lean more heavily on metrics like DRA). So take your mental pie chart for evaluating arms, find the part devoted to carefully cultivated skill, and chop off a slice. Set it aside for now, and know that something like pure, unadulterated fate might be filling the gap and sorting your leaderboards.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now