In the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment, psychologist Walter Mischel studied delayed gratification in children and how the ability to put off a reward at the promise of even greater reward contributed to better outcomes for the kids later. It’s a lesson we’re supposed to learn with wisdom and maturity, but some never do. For them, the immediate consequences are all that will ever matter.

I think about this a lot as I watch Major League Baseball stumble forward, making short-sighted decision after short-sighted decision to maximize short-term profitability. Whether it’s pissing off the players and daring them to strike, or alienating fan bases by refusing to put a watchable product on the field, or making games far less affordable to average fans while catering to the luxury set, these moves seem universally designed to gather as many rosebuds as possible before an impending collapse when fans move on to something else.

I’m particularly concerned about the owners’ latest effort, to contract the organized minor leagues by 25 percent. I live in Iowa City, and don’t have a major league club within 250 miles of me. The Cedar Rapids Kernels play approximately 30 minutes north of me, and sometimes I go there. Thankfully, they aren’t threatened by this proposal. But communities in eastern Iowa like Burlington, Clinton, and the Quad Cities are. If it goes through, there won’t be live professional baseball within an hour and a half of them. Baseball Prospectus’ Rob Arthur and Fangraphs’ Ben Clemens and Meg Rowley have done excellent work on how this would affect baseball fans in Appalachia and southern California. J.J. Cooper of Baseball America suggested over the weekend that, in addition to a way to cut costs, this could be part of an effort to make the minors even more vertically integrated into the structure of Major League Baseball, by driving down franchise values so big league clubs can buy them. The implication is incredibly troubling.

I’m sure that this proposal, if it’s allowed to go through, will ultimately make the current group of owners a good deal of money. But limiting fans’ access to baseball, and discouraging them from attending a game? That’s sure to shrink the size of the sport in the long run. If they’re willing to build for the long term, owners can have two, three, or even four marshmallows later. Marshmallows by the bushel! (I’m unclear as to how marshmallows are harvested.)

Instead their greedy eyes are focused on the one right in front of them, like it might grow legs and run away if they don’t snatch it up first and swallow it first. And eventually, they’ll drive enough of us away that the collapse they seem to be fearing becomes a self-inflicted inevitability.

Whether out of stubbornness or malaise or whatever November feeling sent a man who says, “Call me Ishmael,” to sea, sometimes a person likes to do a difficult thing. Not the kind of difficult thing that has a proper reward or meaningful end-point, mind you — not like running a marathon because you’ve told yourself you could do it, not like finishing a degree in a field you’ve loved so long, not like making croissants at home. Just a difficult thing to do because it is difficult, unpleasant in most measures, and insignificant. It’s important that it doesn’t particularly matter, that no one will care that you’ve embarked on such a thing.

For those inclined toward video games, playing Dark Souls is a good example of such an undertaking. Created by FromSoftware, this 2011 release is well-known for being oppressively difficult. There are so very many ways to die, and several of them are due to the clumsiness of the game itself: a character and controls not particularly designed to jump and yet a non-zero number of gaps and crevasses that must be traversed by doing something like jumping. The scenery of the game is breathtaking if you like medieval architecture (I do), but the architectural logic of the game is both cruel and nonsensical: here is a perfectly rendered stone wall through which a character cannot pass. Here is the spear of some giant monster just skipping through it and skewering you all the same. But only sometimes.

Let me clarify: I’m not even playing this game. I’m spectating this game while someone else plays it, and I badger for more opportunities to do so. Play the game so I can watch, sixteen times in an hour, that stupid red text saying “YOU DIED” heaving onto the screen. Play the game so I can observe a character I’m not controlling slip off a shoddily designed ledge that has to be crossed again and again and again. I watch so obsessively I screw up the pattern on my knitting and have to undo some of the progress I’ve made. I have already ripped back and restarted this project three times. I don’t know why I’m making a lace shawl. I probably won’t wear it, don’t really know anyone else who would, either.

In Dark Souls, there are a lot of unanswered questions. The in-game world is oppressively bleak and how it got that way is mostly conveyed by minimal hints. Most of the NPCs end their dialogue with unsettling laughter. The NPCs who might seem like friends will eventually betray you and try to kill you or go mad and try to kill everything they encounter (including and especially you). I don’t expect the narrative is going to get any more satisfying, or that there’s going to be some kind of payoff that will make this worthwhile, but I want to keep going.

This weekend, while my Dark Souls player is traveling, I chose to go back to summer, to August, and one of the dumbest games of the Phillies’ season: their August 23 loss (11-19) to the Miami Marlins. It’s a Players’ Weekend game, which means that two-thirds of the Phillies’ batters’ bodies disappear against the umpire’s black garb, and the Marlins’ players are trapped in stark white-on-white horrors. The colorful bats are enjoyable, but they don’t make up for how infuriatingly difficult it is to read numbers and names, how frosty and strange the matte white helmets seem. This is my choice between bouts of grading and freezing rain.

The first three innings are delightful insofar as they feature a variety of extra base hits — including a bases-clearing triple by Scott Kingery, because triples are the most fun of all hits — and a very pleasing accumulation of runs. The Phillies lead 7-0 after two and a half innings. The entire lead disappears by the end of the third. I know it doesn’t get better. I leave the game on, knit a few more rows on this shawl. It’s crushing, and stupid, and I still don’t want it to stop.

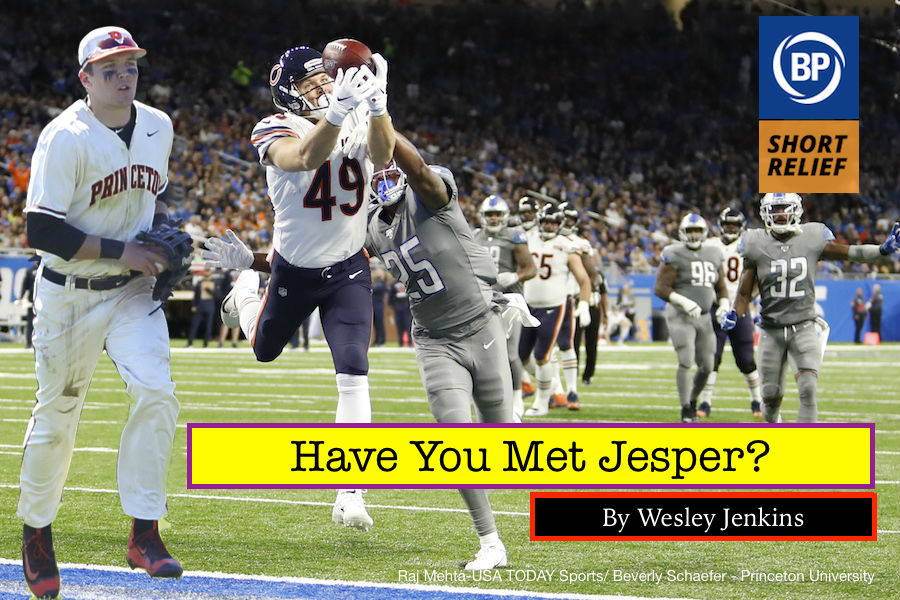

I can’t stop thinking about Jesper Horsted.

For one, his name is Jesper Horsted, a name which naturally lodges itself in the crannies of your imagination and pops up to say “What about…” whenever you need a new name for a new character in a new novel you probably won’t write. “No, no, Jesper Horsted sounds too fake,” you tell your imagination, settling on Rylon Bixby instead.

That aside, I can’t stop thinking about Jesper Horsted because he might just be the most talented person I have ever come across. While Kyler Murray rightfully got all the “best two-way player since Bo Jackson” attention last fall, Jesper Horsted might have deserved a small footnote as well. Some facts about our friend Jesper:

- Attended Princeton University, the number one ranked school in the nation according to U.S. News and World Report.

- Became Princeton’s all-time leader in receiving yards and receiving touchdowns during his four seasons at the school.

- ALSO played three seasons on Princeton’s baseball team, slashing a career .312/.377/.381 at the plate as an outfielder. That’s like Michael Brantley with absolutely zero power!

So Jesper is not only a) extremely smart and b) extremely good at football, he is also c) talented enough at baseball to play at a Division I level. That’s unfathomable to me, a guy who played three years of high school varsity and thought that was cool.

But really, I can’t stop thinking about Jesper Horsted because I wonder if he doubts himself. Here’s a guy who has been good at so much for his whole life, but now sits fourth on the depth chart of tight ends for the truly mediocre Chicago Bears. Will he ever be at the top again? Was this whole sports thing worth it? Should he have just focused on his classes at Princeton or maybe only played one sport? What if he never sees the field again? Was baseball a better option?

Before the NFL draft, Jesper said that he was once in an 0-for-26 slump, so he spent the whole day in the batting cage to reset his swing. Clearly, he believes in himself, but still, I wonder.

Except, on Thanksgiving, Jesper Horsted got to start. All of the other Bears tight ends were hurt, so there went the Princeton kid, at the top of the field once again. And then Jesper Horsted caught the game-tying touchdown, the over-the-head kind of touchdown that so many kids dream of catching one day.

“I don’t really know what happened, to be honest,” Jesper said after the game. He smiled, but you could sense just a hint of doubt. The two-way sports star from the best university in the country had his first big moment. It took longer, but Jesper, like Kyler Murray, probably picked the right sport.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now