“By the time you make it, there will probably be a lot of Indian baseball players.”

This is, word for word, exactly what my sister said to me one night in 1993 as we brushed our teeth at our parents’ bathroom sink while preparing for bed. At that point I was 12 years old and had made three consecutive Pony League all-star teams, the only non-coach’s son to accomplish the feat as far as my family knew. Thus, my making it to the big leagues wasn’t even a question — it was simply a matter of how many of my fellow Indians and Indian-Americans I would eventually be joining there. At that point unfamiliar with the myriad levels of college, semi-pro, and low-level professional baseball leagues and the countless numbers toiling therein, we had no meaningful context or reference point between my own games played just down the street from our suburban cul-de-sac and the ones we watched on WGN every day — and so, the direct path between those two points seemed more a likelihood than some far-flung hope.

The next couple of years did nothing to diminish that hope — there were a couple of junior high no-hitters, a few more all-star teams, the occasional call-up to the JV team as a freshman — as far as I could tell everything seemed to be on track for a Wrigley Field debut sometime around 2003. And I could only assume that any number of other first and second-generation Indian immigrant kids around the country were on that very same trajectory. But then a couple of strange things happened on the way to turning 17 — I stopped growing, and my arm started hurting. My pediatrician — my pediatrician was still my doctor at that time — ever the pragmatist laid the truth out, harsh and bare: “You’re what, 5’8”, 5’9”, you weigh 150 pounds — you’re not going to be a baseball player. So we can do a surgery that won’t make any difference, or you can rest for a few months and you’ll be able to play catch with the kids you’ll have someday.” The matter-of-factness with which he put this stood in direct contrast to the presumption and promise I’d been operating by, and just like that, my dreams of becoming the first Indian professional baseball player were dhishoom’d.

In 2008, an Indian reality show called The Million Dollar Arm led to the Pittsburgh Pirates signing Rinku Singh and Dinesh Patel, cricketers who would go on to become the first Indians to ever play professional baseball. (Their story was later made into a well-recognized but little-seen Disney movie of the same title, staring Jon Hamm.) I followed Rinku and Dinesh’s progress religiously, as they kept a shared blog chronicling the experience of learning a new sport in a new country. With each post I would hope to find news of a stellar outing or perhaps even a promotion, but alas, in fairly short order both Rinku and Dinesh flamed out, neither making it past A-ball. That was the closest anyone of Indian descent has made it to the big leagues thus far, and truly, it wasn’t very close at all.

I’m 37 years old now. If, by some miracle I had made it, my career would most likely be over by now. If I had, I would’ve been the only one. And I would still be the only one. So far. So far.

Photo of Karla Espinoza from Women’s Sports School.

This past week I had the opportunity to attend a scouting school for women in Arizona. We spent our mornings in the classroom, learning scouting terminology, hearing from guest speakers, and sharing stories from our experiences in baseball. In the evenings we went to games and practiced scouting, conspicuous in our purple polo shirts, filling up the scouting section. The men who usually sit in that section didn’t quite know what to do with us; some were solicitous, offering advice, encouragement, their business cards. Others moved seats and sniggered. Most asked who we were with and seemed relieved when we pointed to the male scouting director sitting back a few rows, like we were Victorian ladies in need of a sponsor.

No matter what the response, one thing was unchanging: we were there. We sat in that section I’ve always viewed as bounded with invisible cordons and we took up space. We took up space with our ponytails, our higher-pitched voices, our skirts and our laughs, our purple clipboards. We made that space conform around us. This is what you have to do when spaces aren’t built for you, and there are few if any spaces built for women in baseball; go in there, insist on yourself, and take up space. It was exciting, and empowering, and I left the ballpark every night full of hope and believing there was a space in baseball for me.

School ended on Monday morning, and my flight wasn’t until Tuesday. That night I returned to the ballpark, purple clipboard in hand, and endeavored to take up space again. But without my cohort, I wasn’t part of a wave to be noticed and contextualized, but an annoyance, an anomaly. My questions were answered with terse one-liners, if at all. I was reminded of what one of our guest speakers said to us, baseball’s lone full-time female scout, how her presence was called “fucking embarrassing” by an old-time scout. These scouts weren’t, on average, the old, grizzled type with mussed hair and ill-fitting khakis trailing over scuffed sneakers; they were young, with gelled hair, sharply-dressed in tapered pants and shined shoes, carrying tablets instead of stopwatches and notebooks. They wouldn’t be out of place in a boardroom, a finance conference, Seattle’s South Lake Union district.

As the news about Brandon Taubman’s harassment of a group of female reporters and the Astros’ subsequent denial of the story, broke over Twitter, I looked around at the other scouts in the section, also checking their phones on the inning breaks. None looked perturbed. As my Slack chat filled with links to outraged tweets and my phone dinged with texts from fellow scout school attendees [the timing of this!], theirs remained silent, implacable. As my shoulders sunk, weighted with sadness, they remained confident, upright, as sure of their place in the world as they’ve always been, safe in the spaces they’ve always known as their own.

Dear Colleagues,

I am happy to join the Rays of Tampa as the new “Pitch Tipping Specialist.” I recognize the great risk in hiring an “outsider,” who has never “played baseball,” but these risks will elevate our squad above the Astros of Houston! Over the coming days, I will be applying my unique skills to expose the enemies’ ticks and tells in pursuit of total victory.

The Rays truly are looking into the future. And the future, I am pleased to say, is literary.

I am attaching a copy of my novel and several short stories for you to judge for yourselves the verisimilitude of my work.

Pitch Tip Report: Justin Verlander (Game 1)

Before each fastball, Verlander has a tell. He takes weight onto his shoulders, hunching slightly as if they supported a barrel of barleywine to be trekked across the abbey lawn. His eyes dim, a sort of exasperated emptiness. Then, after gripping the pitch, his face — normally slack and slobish — flickers briefly into a young man of thirteen, prepubescent, cresting into manhood; a bright, eager expression, full of a child’s lust and shame. Then it is gone, and the old barleywine barrel returns.

Fastball, everytime.

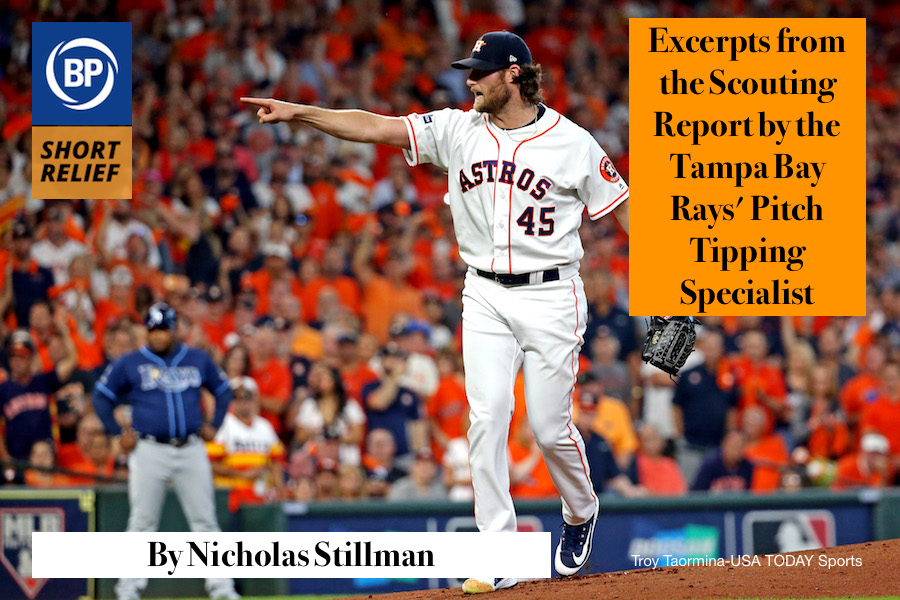

Pitch Tip Report: Gerrit Cole (Game 2)

Thank you all for the constructive criticism. I realize my descriptions, while accurate, were perhaps impractically stated. my wife warned me to speak more plainly to my plain audience. Though of course I reminded her that, plain of not, I deliver only the truth!

Gerrit Cole is a mercurial and enigmatic presence. His face appears at all times serene, like the unbroken surface of just boiling milk.

There is one pattern, however, the trained eye catches. Before the curveball, or, to speak with the precision you have requested, a poorly thrown curveball, Gerrit’s eyes mist over. His legs take in slack and he appears briefly to be in pain. It is the tell-tale sign of doubt and nostalgia. A father, perhaps, hanging on the backstop of his mind — critical of the pitch, critical of the child. You’ll notice an anticipation of his own failure. He will bounce these curves in front of the plate, as his father expected he would.

Do not swing!

Pitch Tip Report: Zack Greinke (Game 3)

Attacking my work is one thing, but the personal insults — I do not watch the games through my rear end, please stop saying this — are unprofessional. It is not my fault the team struck out 15 times.

Maybe it is reading skills that need to be practiced? I could barely understand half of the foul things written about me. My wife read them out loud with difficulty as I sat silent, punishing myself for the mistakes of others.

The game is changing. The Rays of Tampa recognize this shift. The future of baseball will be lead by great thinkers, unique minds. Embrace the future or be left behind.

As I am recovering in a small cabin at an address I will not divulge, I leave you to your own devices against Greinke. Good luck.

Pitch Tip Report: Justin Verlander (Game 4)

Congratulations on muddling through Greinke’s obvious tells.

Not that anyone has asked, but I took another pass at Justin Verlander’s countenance. I have decided to include a short list of possible tells, removing, where possible, the “flowery” language which I am quite weary of having quoted back to me followed by excrement emojis.

What to watch:

Hip twitches

Jaw clenches

Left eyebrow waggles

Glove gyrations

Protective cup shifts

Throwing elbow vein throbs

Nostril flares

Pitch Tip Report: Gerrit Cole (Game 5)

The “experiment” of my employment is not “a failure” just because I “am not expected to return next season.” Despite my uncertain future, I have reevaluated Gerrit Cole free of charge.

Here it is: There is nothing you can do against Gerrit Cole. What can man accomplish against the great forces of nature? What can any of us, of delicate flesh, thin blood, and impotent muscle, do against such unwavering, ceaseless destruction? Take solace in knowing the boat sailed true into the gaping mouth of the ocean. Dignity retained as the ship consumed.

It is apparent that I am, like many geniuses, ahead of my time. Very well.

But please.

Please.

Buy one of my books.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now