At the same time each morning, bright yellow school buses roll down 83rd Avenue in Peoria, carrying Arizona’s teenagers to high schools where they will try out for drama club productions, plan homecoming dances, and study for the SATs, while a group of similarly-aged Seattle Mariners prospects rouse themselves from their beds, get dressed, fix up a little snack to get the energy going, and walk themselves across the six-lane road to the Mariners’ complex, across the street from their apartments.

These are the players from the DSL — the Dominican Summer League — 17 and 18-year-olds who have come to Arizona — many of them setting foot on US soil for the first time — for the Mariners’ high-performance camp, a month-long affair for select prospects to help them gain certain targeted skills. In the case of the DSL crew, this mostly involves time in the weight room and the English classroom, plus nutrition and cooking classes, and the mental skills instruction all Mariners prospects receive. It is, to put it mildly, a lot.

But interview any player, and each one will express gratitude that the organization is willing to invest time, money, and effort in them. (Rent at the apartment complex the players stay in is $1475/month for a two-bedroom). Yes, it is a lot, but they recognize it is for their futures. They talk to their families on the weekends over FaceTime, and keep up with friends back home over WhatsApp. They lean on each other. They play hours of Fortnite. Each one finds their own way to cope.

Yet while the mornings and afternoons are scheduled with meetings and workouts, the coaches and trainers go home to their families when the sun sets, and the international players are left to their own devices in a foreign country, in charge of finding their own dinners, budgeting their meal money for the month against Peoria’s endless march of chain restaurants and SuperTargets. They can’t drive so they rideshare, bike, or walk to the places they want to go. They order off menus in a language that isn’t their native tongue, eat food they’re unaccustomed to, and pay with money that they’re still learning the value of. For entertainment, they walk to the nearby movie theatre or mall. Then they wake up the next day and do it all over again.

This month is the Arizona State Fair, and the players have been sharing the 45-minute ride down to the fairgrounds in Phoenix for an evening of petting animals, roller coasters, and fried foods on a stick. Out of baseball gear, they could be any other teenagers at the fair, just slightly taller and better at the arcade throwing games. But it’s the same wind they feel in their hair as the roller coaster creeps to the top and teeters in that breathless moment of anticipation that needs no language, as they throw their hands up and scream on the downward plunge, their voices joining the chorus of other thrill-seekers; for a moment, just regular kids.

This is for the ones not good enough

The ones who scratched and clawed

But couldn’t change a thing

This is for the ones before victory

Who laid the groundwork down

So that we could rise up

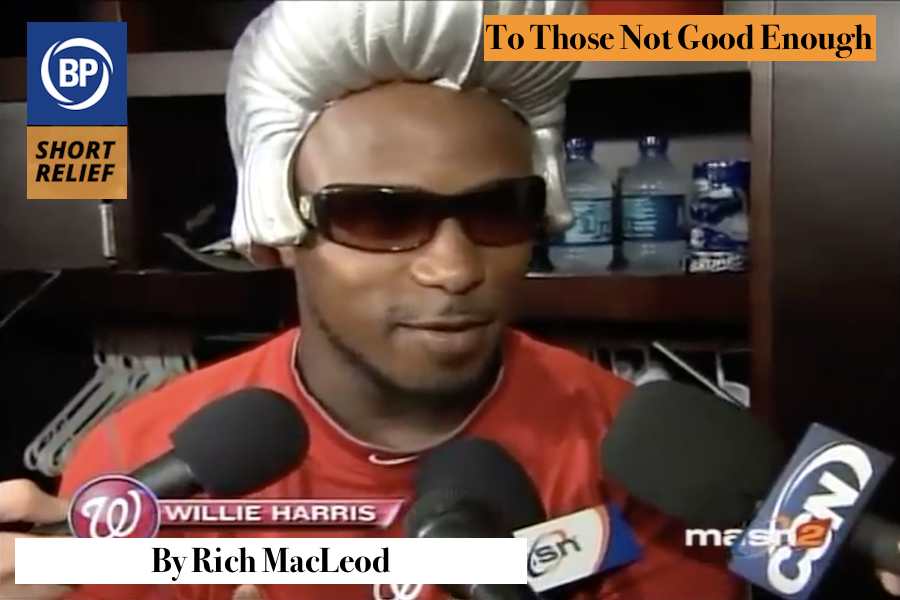

This is for Willie Harris, who flew through the sky

Making other fans talk to themselves

But just couldn’t do much else

This is for Jason Marquis, the one we got

For Cristian Guzmán, the one you forgot

For fill-in starter Garrett Mock

This is for Nick Johnson, who broke his leg

For the set-up man, Sean Burnett

For rockheads and Sharks and Tony Plush

This is for the ones who tried their best

A guy named Nook, Lannan the ace

Adam Dunn hitting dingers to space

This is for the ones who ran and fell

Bergmann and Redding

MacDougal, Justin Maxwell

This is for the ones that made the journey extra sweet

For Acta and Storen, who once had their share of defeats

But today we are league champs, awaiting what team we’ll meet

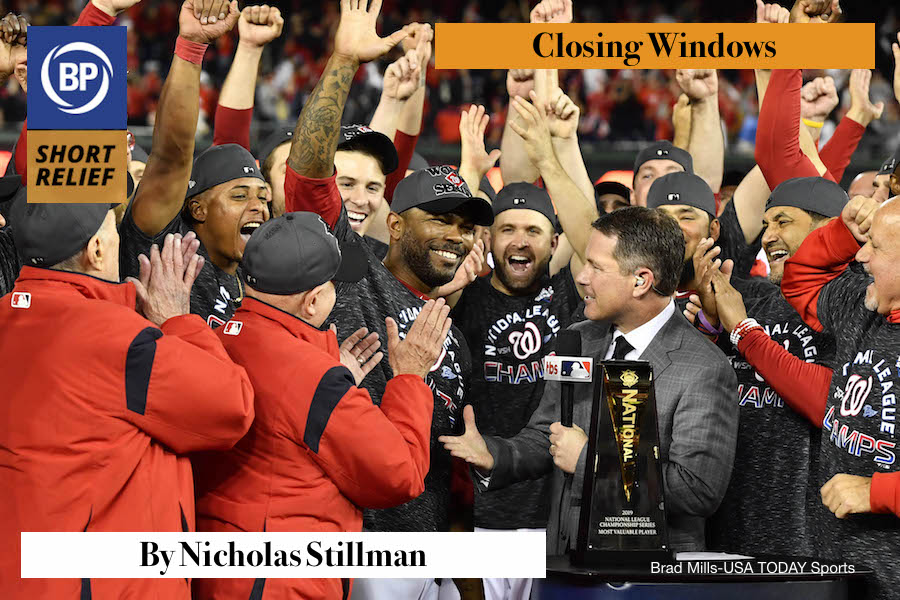

The Washington Nationals are going to the World Series, which makes me happy. Not because of the end of their narrative — “The oldest team to never make a World Series” — but because they are the oldest team — 18 players on their playoff roster are over the age of 30. I notice these things, now. I catch myself scanning bios, counting backwards or forwards from the players ages to mine, and using the resulting math to determine how I feel about myself.

I turned 28 yesterday, still solidly in my playing prime. The day before, I watched Howie Kendrick hit three doubles in one game. The postgame coverage focused on one particular aspect of his achievement: “I mean, you see the man. He’s what, 36 years old, and he’s still doing it,” said Rendon, adding that when he’s 36 he’d be “on my couch hanging out with my kids.” The headlines, too, included Howie’s age, remarking on it as if small miracle had occurred. Baseball players don’t have an expiration date, per se, but they do have a Best By date. Everyone recognizes Howie has surpassed his.

When I was 23, I worked as a barista to save for graduate school. The last drink I made was for a regular customer who knew where I was going. He shook my hand and held it there, meeting my eyes. “This is the last cup of coffee you’ll ever have to make for someone. It’s an honor to be the last one. You’re onto bigger things now.”

I believed him. I said my goodbyes, cried a bit, and the next morning I climbed into my car and drove south, thinking my life was about to unfold in new, promising directions. Two days ago, I cleaned a latte off the floor. My life has not followed the trajectory I anticipated: a steady climb from novice to expert. If it did, I would be at my peak, not leaning in as a customer whispers there’s a “bit of a mess” in the bathroom which “requires attention.”

I’ve internalized the language of primes and declines and I’ve become nervous that I’ve wasted mine, that I missed the window of my peak. I feel a slow knotting of my shoulders, a slight sting of embarrassment when I put on my uniform, an aversion to discussing my age or job. I can’t mention the well-rejected novel “waiting for the right agent,” or my short history of achievements quickly fading into memory. Once you’ve started to think of life in the terms of the MLB playing career, the world begins to seem more hostile, less forgiving, filled with closing windows and quickly shut doors.

But I watch Howie Kendrick, Fernando Rodney (42), Ryan Zimmerman (34), Kurt Suzuki (35), and Max Scherzer (35), and it wears the edges off my anxiety. Between my mornings typing words I’ll likely delete, my job I thought I’d outgrown, and nights when I watch the blades of my ceiling fan and think about the time I have left: the Nationals, a team that should be in their decline, a team that has missed their peak, wins.

When Howie Kendrick won the NLCS MVP award, they asked him about his path to that moment. “I feel like being around this long, I wouldn’t change anything about the past,” Kendrick said. “Because this is just — I mean, it’s unbelievable.” Not everyone gets their moment, not everyone’s story ends with a trophy and reporters around to ask the question. But the Nationals as a franchise and as a group of men remind us that there is still time; the clock won’t run out on you. If we have a window, it only closes when we stop trying to keep it open.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now