Farhan Zaidi closed the door behind him. He slowly, carefully checked the sole of each shoe in turn before walking away. The Giants were going to the wild card game.

***

Mike Rizzo still couldn’t quite believe that San Francisco had made it. The Phillies had been oddly subdued in the final week as they capitulated to his Nationals. The Diamondbacks had failed to score a run in their series with San Diego. The Cubs had given up both the division and the wild card spot with a series of bizarre decisions. No-one in Chicago seemed to be available for comment.

Rizzo hung up the phone. Still no answer from Theo.

Mike? Farhan wants to talk to you, his secretary said.

Fine, fine, put him through.

No…he’s here. Right now.

He’s what?

Zaidi walked into the office. He stared at Rizzo until he shifted uncomfortably and looked away. Zaidi carried on staring.

Can I help you, Farhan? Rizzo said. The game isn’t until tomorrow.

What’s the most you ever saw lost on a coin toss?

Coin toss?

Coin toss.

Rizzo paused. He looked back at Zaidi and then away again. Zaidi produced a quarter from his pocket and flipped it deftly between his knuckles.

Am I missing something? Rizzo said.

Zaidi said nothing. He placed the coin between his thumb and forefinger and flipped it spinning high into the air. He let it land on Rizzo’s desk and then slapped his hand down firmly over it, just missing his Max Scherzer bobblehead.

Call it, he said.

Call what? What are we even doing here?

The game. Everything. Call it.

The game? Tomorrow’s game? Are you kidding me?

Of course not. The coin got here the same way I did. The same way the team did. Call it.

What happened to Theo?

It was always going to happen. I had no say in the matter.

Rizzo moved over to his desk to pick up the phone. Zaidi immediately stepped into his path to block his way, still holding his hand over the coin.

Call it.

Rizzo stared back into Zaidi’s unblinking eyes. Zaidi reached up and took off his glasses and tightened his grip over the phone. Rizzo felt a drop of cold sweat slide down his temple, trickling down onto the line of his jaw.

This is insane.

No. This is how it always had to be. Every choice. Every pitch. Every bounce. No play can be erased. Call it.

Rizzo swallowed and looked down at the hand covering the coin and then back up at Zaidi.

Heads, he said through gritted teeth.

Zaidi finally broke his gaze and looked down at the coin as he lifted his hand.

Heads, he said. Well done.

Zaidi picked up the coin and handed it to Rizzo.

This is yours now, he said. Good luck against the Dodgers.

He turned and walked away without another word. Rizzo watched Zaidi through the open door and waited until his footsteps had faded away down the hall before he tottered and grabbed the desk for support. He wiped the sweat from his brow and looked at the coin and then collapsed back into his chair with his head in his hands.

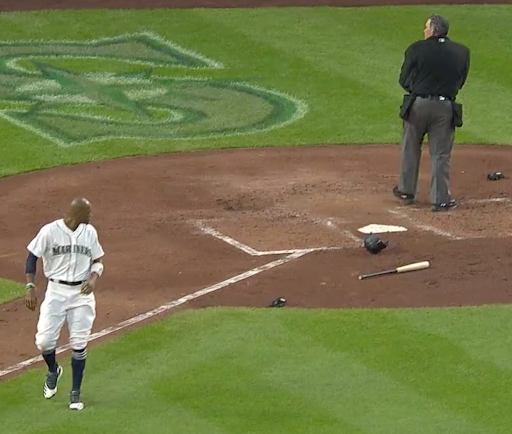

If you grew up a Mariners fan in the 80s or early 90s, you probably knew Lenny Randle’s name, not so much for his play, but for the famous incident where he got down on his hands and knees a blew a ball foul, which was later ruled to be illegal because players “can’t interfere with the path of the ball” or something that definitely doesn’t sound like it was made up on the spot after a player did something out of the lines. Out of the lines kind of defines Lenny Randle’s career, though. If you didn’t know him for FoulBallBlowgate as a Mariners fan in the 80s, you might have known him for this star turn in one of the Mariners’ famous commercials:

If you haven’t watched the Jacket Night promo and don’t click on videos in stories you read on the internet, one, that’s probably smart, and two, please suspend this rule momentarily and watch the video, which is one of the most perfect pieces of 80s cinema ever. The soft focus! The ruffles on the tux! Those 80s Mariners uniforms with stirrups! The relievers as backup singers (who I don’t recognize but they look like relievers, don’t they?)! I would sell a kidney for one of those jackets.

And yesterday on Twitter, Lenny Randle had another moment in the sun when a tweet of him going out of his way to truck a pitcher who had thrown at him went viral (caution: NSFW language in the tweet, and probably in the video, although there’s no sound):

Again, this is Lenny Randle going outside of the lines, in this case literally. The tweet attracted mostly positive reactions on Twitter, with people praising Randle for being a “savage,” or bemoaning a lost era of baseball (the era where people routinely got their faces beaten in, I suppose). “Now that’s baseball,” sighs someone with the display name “Not Your Average Savage.”

Perhaps the narrative around Randle — a random player from the 80s who most people on Twitter, which skews young, hadn’t heard of outside his “taking matters into his own hands” — would feel a little different if people knew that when Randle lost his starting job in Texas he confronted his manager at batting practice; the confrontation turned physical and Randle beat his manager, Frank Lucchesi, so badly that the older man was hospitalized for a week and required plastic surgery to repair his cheekbone, broken in three places.

Going outside the lines can be exciting, thrilling even. The greatest lives are lived outside the lines, those who do what supposedly cannot be done, who walk in places other people can’t see. But there’s a dark and destructive side to it, as well, when someone decides to write the rules for themselves, and it’s important to remember that a tweet isolating one moment of “savagery”, a viral video, a light-hearted joke, can hide an angry, idiosyncratic darkness.

The practice of dueling can be traced back to the 5th century, when King Gundabald of Burgandy declared armed combat between two parties a legal form of settling disputes. That was a judicial process, sanctioned by a government, which was further popularized in Medieval Europe (the knighting ritual of striking the kneeling knight twice with a sword followed by a blow to the face symbolized the last time a knight would let himself be struck without chivalrous retaliation). Most modern understandings of dueling, however, takes place outside of the courts—The Duel of Honor. During the Italian Renaissance illegal dueling became popularized as a way for aristocrats to obtain or maintain rank. The medieval gauntlet replaced by a glove, the sword replaced with pistol.

We find a description of this in The Book of the Courtier (1528), which describes the necessary components for a duel as when one “finds himself so far engaged that he cannot withdraw without reproach….” It is a matter of honor and of ego, not necessarily the slight itself that brings on the duel. An insult can be easily brushed aside, a slight forgotten, but when one feels they will lose face? Such as the case of two Italians who dueled over poets that one of them had never read but would not stand to hear them insulted? The glove is dropped. The glove is lifted. The duel commences. Blood is shed.

The rules for such a duel were laid out in detail in The Code Duello: The Twenty-Six Commandments (1777), an Irish penned compendium of codes for the “government of duellists.”

By following the twenty-six codes two parties who found themselves unable to “withdraw without reproach” were able to handle their disputes as gentlemen on a field of battle.

I. The first offence requires the first apology though the retort may have been more offensive than the insult.

III. If a doubt exists who gave the first offence, the decision rests with the seconds.

Code IV. When the lie direct is the first offence, the aggressor must either beg pardon in express terms…or fire on till a severe hit be received by one party or the other.

VII. But no apology can be received in any case after the parties have actually taken their ground without exchange of shots.

IX. All imputations of cheating at play, races, etc….may be reconciled after one shot, on admitting their falsehood and begging pardon publicly.

XIV. Challenges are never to be delivered at night, unless the party to be challenged intends leaving the place of offence before morning; for it is desirable to avoid all hot- headed proceedings.

XV. The challenged has the right to choose his own weapons unless the challenger gives his honour

XVI. The challenged chooses his ground, the challenger chooses his distance, the seconds fix the time and terms of firing.

XVIII. Firing may be regulated, first, by signal; secondly by word of command; or, thirdly at pleasure, as may be agreeable to the parties.

XX. Seconds are bound to attempt a reconciliation before the meeting takes place or after sufficient firing or hits as specified.

XXI. Any wound sufficient to agitate the nerves and necessarily make the handshake must end the business for that day.

Thankfully, the days of dueling have all but disappeared—civility, due process, and two game suspensions are the standard recompense for disputes. Though on occasion, and in secret, duels are still practiced, are still carried out according to ancient laws. The flames of honor still stoked by the blood of the courageous. In some places, the Art of the Duel still lives.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now