Copley’s mind was on his dinner as he watched the couple shepherd their two children down the tree-lined path away from his building. He’d been marinating a steak all day and was planning to grill it in the shared picnic area behind his apartment building, in the last of the good weather before the chill of the fall set in for good. And after that it would be snow, and it would snow, and snow, and snow, and the crowds would thin, and then disappear.

Not that the crowds at his section of the Hall were ever overlarge. “It’s an easy job,” said Shepard, whom Copley had replaced. Shepard was old and stooped and had been working at the Hall since it was all contained in one building. He had many stories to tell about baseball back in his day, and he managed to tell Copley most of them during an interminable, boring training period, during which Copley spent a lot of time thinking about various meats and how to grill them on his new communal grill, and if his cute neighbor from 3B might come out, and he could say, “Hey, I made too much,” and that was usually the point where Shepard sighed and abruptly cut off whatever story he was telling about Mike Trout, who had an entire wing to himself — it wasn’t like Copley didn’t know all about the National Weatherman. “Don’t worry, you won’t see many people,” was the last thing Shepard said before he walked out the door on his silver cane, as close to a benediction as he could offer.

And Copley hadn’t. Building 7, Annex 12 was located towards the back of the HOF campus, up a hill that was difficult to ford when it snowed, which was often. Besides the plaques — a full day of viewing on its own if you did it right, which no one did, according to Shepard — people wanted to see the extremes: the Golden Era, housed over in Building One, or the Current Era, on the other side of the horseshoe of the grand entrance, where players sometimes showed up unexpectedly. The docents over in One and Current were all bright-eyed and shiny-haired, or wizened and venerable like Shepard, the coots and the CITs, Copley called them. Their idea of a good time was hanging out at the museum after hours and taking special guests on VIP tours.

People were not as interested in Building 7, the 2010s: the strike era, tanking, shifts, the juiced ball, although they weren’t supposed to call it that. It was the pre-modern ball. Shepard had called it the juiced ball, and so that’s what Copley called it, unless his supervisors were around. Mostly the visitors were nerds interested in the Age of Analytics display; they’d crowd around and laugh at the technology that had seemed so advanced. Sometimes Copley felt a little bad for the Rapsodo machines, lying there inert like etherized patients on a table, but he quit feeling sorry for them when it was time to dust all the bulky, fiddly instruments.

The other people who came to visit were the completists, like the family he’d just shown out, who needed to see every nook and cranny of the museum. The father was the worst type, grimly insistent that everyone learn and enjoy, and Copley felt a deep kinship with the daughter who flopped down on a brown leather bench and refused to move because it was all too boring. The father murmured an apology on the way out, but Copley just shrugged; it was boring. History is peaks and valleys, and sometimes just a big boring plateau.

Copley locked up Annex 12 after the family left. He was unlikely to see anyone else, and plus, he reasoned, he had such a longer walk than any other employee. And he shouldn’t let the steak marinate too long, after all; it would pass the point of tender and become mealy and unpleasant. “All things in moderation”, Shepard was fond of saying, gesturing around with an ironic flick of the wrist.

There was a group playing a game on the fields below the hill Copley walked down, one of those historical re-enactor or re-creationist or whatever groups. It looked like the pitcher was taking a turn to hit, and everyone was laughing, hands on their knees kind of laughing, the kind that hurt your belly. Copley remembered what it was like to laugh like that. He paused by the field briefly, then remembered his steak, and the neighbor in 3B, and hurried on to his car.

The following was made possible through the graphical contributions of Tee Miller

As an English major twice over, my brain struggles to reduce tables of numbers into clear concepts. It craves pictures, words, graphical representations. Which is why my love for Baseball Prospectus’ Pitch Tunneling Data, is hampered slightly by my inability to process the information quickly.

My colleague Tee Miller and I have taken on the challenge of creating — free of charge mind you — a way to add graphics to the numbers to assist the numbers impaired. It’s called the Visual Tunneling Metric, or V-Tic.

For the V-Tic data we are using BP’s PreMax, which measures the distance, in inches, that two pitches appear separated at the batter’s decision point.

Here’s a sample.

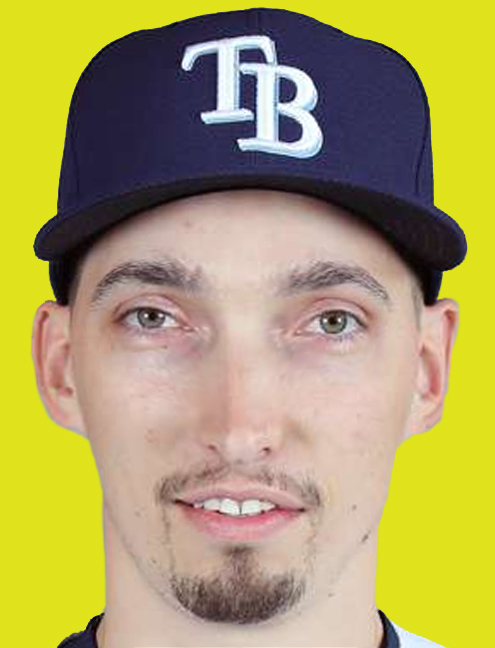

Reliever Nick Anderson is one of the best pitch tunnelers in the game. He’ll be our benchmark. He throws two pitches: a fastball and a slider. When Nick Anderson throws his fastball, according to our graphic, it looks like this.

A perfectly normal Nick Anderson fastball begets a perfectly normal Nick Anderson face.

Now, as a right handed hitter, you better believe Nick Anderson will throw you a slider after his fastball–it’s his entire strategy.

To your trained and competent eye, the slider would look like this.

Is that the same photo?

Look again.

Notice the slight drift of the eyes, the tug of the lips, the bulge of the skull. The image has been warped 1.09 inches. This is it. This is the metric: the V-Tic. Quite simply, the more attractive the second face, the less pixels of distortion, and therefore the more deceiving the pitch.

This is what a hitter would see if Nick Anderson’s head was approaching at 87 miles an hour. Could you spot the difference? Would you swing? At Nick Anderson’s face?

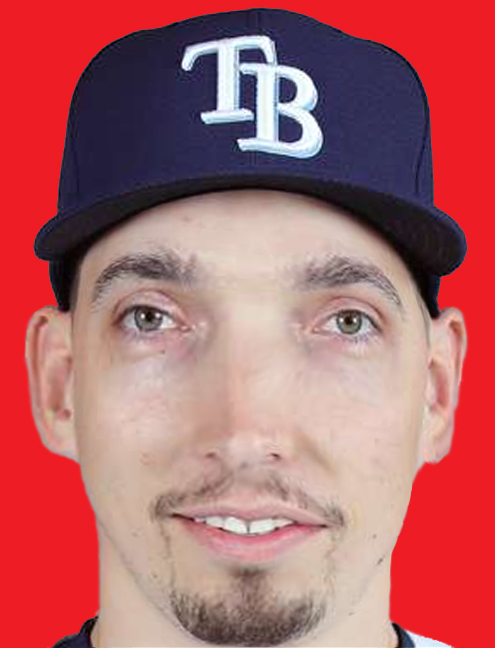

Now for someone a bit more familiar. Blake Snell has the distinction of having the most closely paired fastball/curveball combination in baseball.

The fastball, free of other pitches:

A handsome pitch, to be sure. Gorgeous, evaluators might be overhead mentioning.

Now, a curveball. What does a curve look like at the decision point following the fastball?

Uncanny, barely noticeable. An attractive pitch that is easily deceiving. Only 1.1 inches of separation means only 1.1 inches worth of distortion.

What about, in this imaginary sequence, if Blake Snell throws you a changeup after dazzling you with a curveball?

Now we are starting to see some separation.

Ew! A hitter might say. Gross! Disgusting! What is that, they scream, 1.65 inches? Yes.

Still, Blake Snell is one of the best. We haven’t even gotten to average. What’s average look like? Who is the most average tunneler in all of baseball?

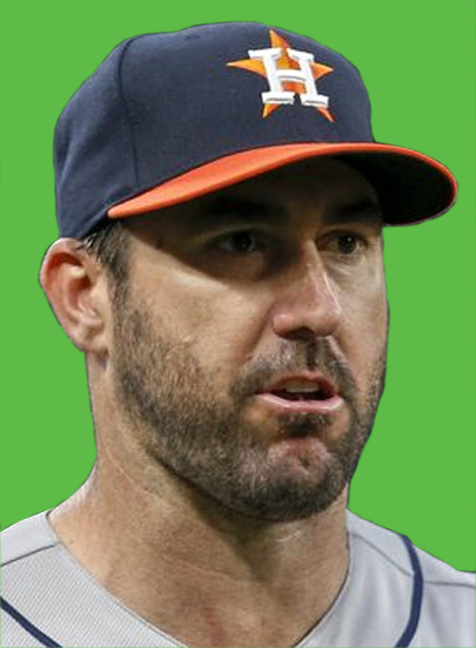

A curveball from the Ageless Wonder at 79 MPH:

Then, a slider at 87 MPH:

That’s 2.65 inches of Verlander Face.

We are reaching it: the outer limits of the V-Tic usability. Verlander has pushed it, but it is not broken. There is still some semblance of the original left, still some gas left in the tank.

Oh, no, you may be thinking. Not Clayton. Kershaw, you say, is untouchable.

Let us see.

Clayton Kershaw decides to throw you a slider.

The most handsome slider you’ve ever seen. Intimidatingly handsome, actually. You hate it though you have no reason to.

Kershaw lobs you a curveball on the next pitch.

It’s 2.88 inches of pure horror. You drop the bat. You run. You run and don’t look back. Don’t ever look back at Clayton Kershaw. You leave town, join a friendly cult, the cult dissolves, you get locked away, you close your eyes, you see it still. You will never truly be free. Not of this.

Conclusion

That brings us to the end of the example. We chose extreme samples from recognizable pitchers in order to demonstrate the V-Tic’s range. Many of these will be touched up, the kinks ironed out, etc.,before implementation. Soon, every pitch pairing on BP will come standard with a V-Tic for increased readability.

Assuming, that is, that the BP Brass has received the 200 manilla envelopes we mailed to their private addresses.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now