The Women’s Baseball World Cup was held in August 2018 in Viera, Florida, with all the games broadcast on YouTube. The tournament was, simply, fun as hell to watch: A mix of blow-outs and tight games, lots of contact, a few devastating strikeouts, and some long ball for those of us that dig it.

I’ve tried to distill it into a few key players and images – ones that hopefully tell a larger story about both the tournament and women’s baseball game style. If you’re looking for players or teams to watch – or games to check out – I’ve tried to make a few suggestions of where to begin.

Ayami Sato

It’s hard to pick just one image or stat that tells you how good, exactly, Ayami Sato’s curveball is. One of my first, and most enduring, memories of baseball’s return to DC was watching Liván Hernández pitch. He was a junkballer generally and would occasionally breakout an eephus so slow and meandering and occasionally devastating, that it was a joy to watch hitters boggle at it at a time when being a Nationals fan was not really that much of a joy about anything.

Sato’s curveball doesn’t feel like it has quite the same meander, but it has the same devastation. It’s a sliderish curve that both drops and moves, with a spin rate of 2150 rpm (per Pitching Ninja) and velo in the low-60s, about 10 mph below her fastball. It is knee-buckling; it is gross; it is wonderful.

Ayami Sato, Filthy Curveball. 😷 pic.twitter.com/rINrLEVwvi

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) September 1, 2018

Ayami Sato, Beautiful Curveball. 🌈 pic.twitter.com/Vt38gYyTc8

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) August 28, 2018

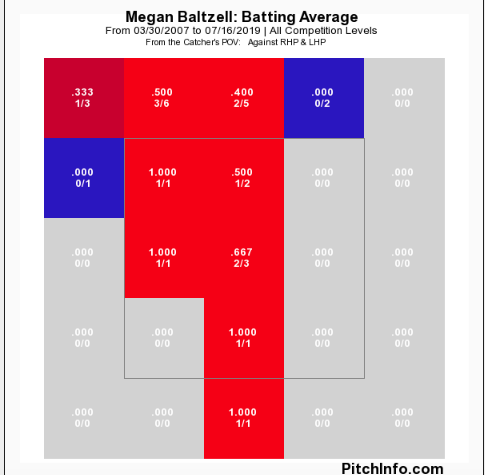

Like many of the best pitches, batters know it’s coming – she throws a four-seamer and a slider, though the data available here generally incorporates the latter into her curveball metrics – but are generally powerless to actually do anything about it. There’s no real question of what it is coming out of her hands – the velo and drop aren’t exactly a surprise – and yet she uses it to lethal effect. For the 2018 WBWC, her BAA versus right-handers using that curve was literally zero. The best batters could hope for was getting hit as a way to get on base, and even against lefties she gave up only two paltry singles off that curve the entire tournament.

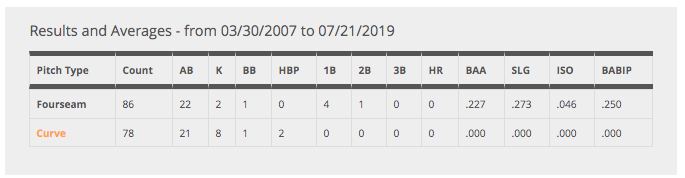

Sato against right-handers:

Sato against left-handers:

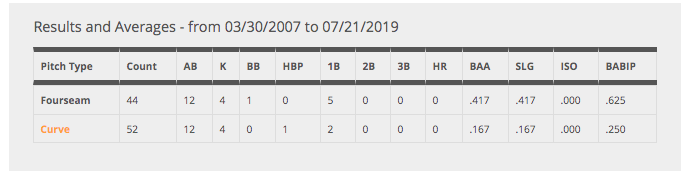

Sato against all batters:

She threw a complete game shut-out against Team USA during the WBWC super-round (highlights available here) surrendering only one hit to Megan Baltzell, the women’s baseball equivalent of watching Max Scherzer pitch to Mike Trout in the World Series. (Look, I can dream.)

Megan Baltzell

Megan Baltzell is a lefty power-hitting catcher with numbers so good they defy comparison. She had 13 hits in 26 at-bats – plus seven free passes – with two of those hits for homeruns over the course of the 2018 WBWC tournament, putting up an OBP of an absurd .606, and a Yelichian (Troutian, Bellingerian) OPS of 1.491. She is very very fun to watch hit, and she hits the ball a lot.

GOING GOING GONE (again) 💪🏼

Our second home run of the night and Megan Baltzell’s second of the #WomensBaseball World Cup puts us ahead 4-1! #OurGame pic.twitter.com/SPWKrN7X32

— USA Baseball WNT (@USABaseballWNT) August 29, 2018

HOOOOOOOOOOOOOME RUN 💪💪💪 Megan Baltzell 🇺🇸🇺🇸🇺🇸 !!!!!!!!!!!!! #WomensBaseball #WorldCup @usabaseballwnt pic.twitter.com/RolDzMEbYt

— WBSC ⚾🥎 (@WBSC) August 25, 2018

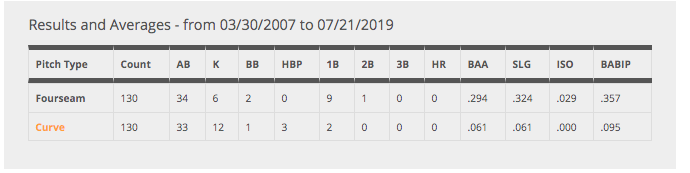

Perhaps most devastating is that, in addition to hitting the ball far enough to take a catcher-fast jog around the bases, she utilized all parts of the zone. No surprise that her batting average zone profile looks like a dagger.

I wrote this piece with the idea that I wouldn’t address the question that I feel is too-often addressed in pieces about women’s baseball and women’s sports in general: Can they play against male athletes or in the majors, etc.? I’m not particularly interested in that question, because comparison is, in many ways, the death of enjoyment. I want to enjoy Baltzell’s hitting on its own terms, in a way that says, to paraphrase Vonnegut: If this isn’t good, I don’t know what is. It’s a privilege to watch someone who’s that good do their thing, much like Sato’s curveball or some of the fielding I’ll talk about later. So, I’m not interested in the question of if and how she could hit major-league pitching, even if I think the answer is ‘yes’ and ‘far.’

But I would give at least a tooth to see Baltzell compete in a Home Run Derby. The NHL did something similar earlier this year by having women’s league players compete in the All-Star Skills Competition, though initially didn’t offer them compensation for their time. The NHL All-Star Game is always something of a snoozefest, for both the players and viewers – the League even suspends players who come down with I-don’t-really-want-to-do-this-itis – but, like the Home Run Derby, the Skills Competition is much more fun than the game itself. It would be amazing to see the MLB put its money and time where its lip service about women’s baseball is and invite players like Baltzell to compete in a Derby or compete in a skills-style competition or in a game showcase similar to what the NHL does.

I watched the 2017 Home Run Derby in a fit of giggling disbelief from my living room floor, as Aaron Judge hit home run after home run all over Marlins Park. Watching Baltzell crush the competition yielded the same feeling of effervescent devastation – one that shouldn’t be confined to a bi-yearly tournament.

Leonela Reyes, Migreily Angulo, and Sor Brito

The best game, in my mind, of the tournament was a 3-1 U.S.-Venezuela game that featured a Baltzell home run and some amazing pitching and fielding by Team Venezuela. (The link below starts a few hours in because of a weather delay for the game.) I would rank it on par with the Dominican Republic-Puerto Rico game from the 2017 World Baseball Classic in terms of rewatch-ability and sheer fun.

I’m not a big fan of defensive metrics – their inter-site reliability tends to over- or under-value players (see: Rendon, Anthony, whose differences in WARP and fWAR are largely driven by defensive metrics), and many fielding metrics fall apart when you look at their components. That doesn’t mean I’m not a big fan of fielding, in particular the fielding during this game. As of right now, there aren’t fielding metrics for the WBWC available on the Baseball Prospectus site. The WBWC site does offer fielding metrics, though with the caveat that they aren’t filterable by position. The metrics offered (putouts, assists, and errors, and fielding percentage, which incorporates all three, as well as double-plays turned) tend to put first basemen at the top of the leaderboards.

In my mind, the best defensive plays of the tournament came at three points during this game: One, a bases-loaded two-out catch by Leonela Reyes at the fence to end the top of the first inning, leaving the U.S. scoreless in the first for the first time in the tournament. It’s not in-itself a spectacular catch – Reyes runs a clean route to the wall and makes the grab – but like many of the best defensive plays, it looks right in its execution, particularly in a high-stress situation with the U.S. waiting to bust the game open.

Leonela Reyes makes an inning-ending catch at the wall.

The next catch came in the sixth inning, a beautiful on-the-move grab by Migreily Angulo that turned an extra-base hit into an out. It’s an athletic move, a catch made facing away from the field and hustling toward the outfield wall. It’s one of those plays that doesn’t translate well into the provided fielding metrics – a less mobile player wouldn’t go to make the grab, and therefore wouldn’t necessarily be charged with a ‘chance’ if she’d missed it on an error.

Angulo’s listed fielding metrics are fairly unspectacular, but that’s more a shortcoming of how her fielding was being measured than her actual play. She gets a good bead on the ball, running to snag it, and then immediately puts the brakes on before a collision with the fence; in other words, a set of decisions and actions that are recorded as a simple ‘putout’ but show off the kind of skill that make something spectacular look routine.

Angulo robs the US of an extra-base hit at the top of the 6th.

The third great defensive move also occurred in the sixth inning, a diving catch by Sor Brito, Venezuela’s shortstop, who lost her footing in denying Amanda Gianelloni a hit.

Brito hustles to rob the US of a hit in a one-run game.

This catch is, perhaps, the opposite of Reyes’ – rather than showcasing the simplicity of a clean route and good placement, Brito hustles out of position, making a grab at the edge of left field, a hustle-and-heart kind of move that asks for speed, positional and situational awareness, and the willingness to go to the dirt to make a great catch, in a 2-1 game where pitcher Kisbel Vizcaya had already thrown more than 100 pitches. (Vizcaya was 17 at the time of the tournament, and able to hold the good-hitting US team to three runs over seven innings, though fared less well against Japan in a later game.)

It’s one of those plays that’s beautiful in its ugliness, the kind of thing that’d make for a blooper reel if it didn’t work, but somehow does, Brito emerging from her fall holding the ball up before jogging toward the dugout. A baseball move, the kind that feels particularly diminished in a box score, something beyond what a leaderboard – at least these leaderboards – can really tell you. Something you gotta see to believe.

This isn’t an exhaustive – or attempting to be exhaustive – look at the Women’s Baseball World Cup or women’s baseball in general. I didn’t talk about Janiliz Rivera, a catcher from Puerto Rico, who slugged 1.40 against breaking balls. Or Jade Gortarez, shortstop and pitcher for the U.S. who didn’t strike out the entire tournament and who swung, and made contact, on almost all of the pitches she saw. (It was good contact too – she put up an OBP above .500 and an OPS of 1.212, in addition to pitching five innings of two-earned-run ball.) There’s a lot to see in the data that BP and its partners has exhaustively compiled, and a lot good to see beyond that. The World Baseball Softball Confederation hasn’t yet announced where the 2020 WBWC will be; wherever it is, I plan on watching and cheering, and I hope that you’ll join me.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now