I sometimes like to see the flag

flapping at the top of a construction

crane. The loneliness of the flap,

the anthem’s punch line, consoles

me like the moon or a good cloud.

When a vulnerable person sings

the anthem, the crowd sweeps

me up in the swell. I can resist

strong performances; a wavering

breath and my disarmament is total.

Ceremony is sentimental and its

mechanism functions and it functions

on me and my tear ducts and simple

imagination. Tell the story of a leader

and every listener will imagine herself.

Some pomp belongs in stadiums.

I prefer arriving fashionably late

and missing it entirely, but you keep

catching me crying at a montage

or confessing that Astronomy 101

made me want to grow up to be the

director of a government agency.

When I cry at a ceremony, I hate it

a little, but I wish I hated it more.

Sunday’s Braves-Tigers game had an unfamiliar voice in the booth on the Tigers’ side. It wasn’t Kirk Gibson or Jack Morris, and he was spitting a glut of minutiae on pitching. It was refreshingly interesting. It turned out to be Todd Jones, that Todd Jones, the closer you watched through your fingers. He did surprisingly well for several innings. Out of habit I turned it off for the ninth.

Then Emma did a thing yesterday on the most memorable closer by team, and selected Jones, so now with two sightings within a fortnight I am forced to create paragraphs on Todd Jones and his anachronistic arc as a ninth inning guy, a type of closer that will probably not exist again.

Starting with the Astros, he eventually became the de facto closer for The Bad Tigers (and a one-time All-Star/top-five Cy Young finisher with platinum blond facial hair, why did he do that). Then he was passed around from team to team as middle relief empty calories, only to land in Florida, as one does, saving 40 games and reviving his career, but parlaying it into a hair-pulling experience. You are always a little uncomfortable when your closer is pitching, even when it was Rivera. Now imagine that it was Todd freaking Jones. Imagine your closer literally having the nickname “Roller Coaster.” In some ways I felt more comfortable when the bases were loaded in a one-run game because muscle memory told me that Todd Jones had the other team right where he wanted them.

He was the closer when the Tigers won the AL pennant, and he’s only one of three pitchers to save over 30 games with a K/9 under four, the others being Danny Kolb’s weird All-Star year in 2004 and Dan Quisenberry five times. The difference is both of those pitchers were groundball specialists, and Todd Jones was not a groundball pitcher or a strikeout pitcher, but more of a mustache pitcher.

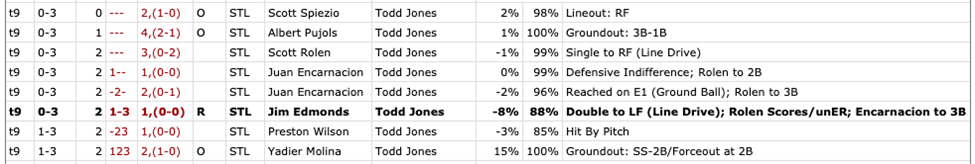

Why was he on a spot TV appearance over the weekend? It’s kind of like saying why did he have 93 saves and 75 strikeouts in his final three seasons? These are simply not questions for us to ask, but rather to try to admire that they did happen, and be happy for the anomalies, because strikeouts are way the hell up and the booth is no place for a pitcher who retired batters mostly through diplomacy. But it is very important to share the play-by-play of his exactly one career World Series save. Had it all the way.

Many writers suffer from imposter syndrome. They worry that their obvious deficiencies, obvious compared to the unknowable facade of their successful colleagues, will be exposed. That their work will be torn apart or, worse, disregarded. I don’t have this problem. Not because I think my writing is particularly strong or important, but because I’ve never been good at comparing myself to others anyway. I write like me, and most people, I’ve found, aren’t as good at writing like me, strangely.

I do suffer from imposter syndrome, but it’s because I feel like a fraud of a baseball fan. I’ve never quite found myself able to buy into the usual momentum of fandom. My default baseball memory has no baseball at all: it’s of sitting in the sunlight outside the Triangle Pub on Occidental Avenue, a two-dollar plastic cup of beer in one hand and a Russian novel in the other, walking empty concourses with a friend ignoring a hundred-loss team below, like angels disinterested in the work of mortals. The game stresses me out when my team plays too well; I get bothered by the concept of winning, the need to win, the demand to win at all costs. It’s a necessary element of sport, and it feels inhuman and it ruins everything.

There are times when I consider that maybe baseball isn’t for me anymore, that I need some other subject against which to cast my shadow: movies, books, the idiocy of the public. Something that isn’t so efficient, so easily calculated. And then I think about Dick Williams.

Dick Williams was a Hall of Fame manager, a beloved crank, and an absolute disaster for the 1980s Seattle Mariners. He arrived in tandem with an amazing corps of homegrown talent: Alvin Davis, Mark Langston, Mike Moore, Harold Reynolds, Jim Presley, Phil Bradley, Ivan Calderon, Danny Tartabull, Dave Valle, Bill Swift, Dave Henderson. There’s a reason you might not recognize many of those names — they’re Mariners, after all — but they were all twenty-win players, or could have been. It was fertile ground and Williams laid waste to it. He hired sycophants and identified/created enemies, blaming them for the team’s cold streaks before trading them off for pennies on the dollar. He shipped off Calderon, Tartabull and Bradley for nothing, played them out of position (Tartabull at 2B!) or forced them to grind through injuries and complain about their stunts. By the time Williams was forced to retire, the team was back in the cellar.

Williams’ politicking extended beyond his own career; he published a memoir in 1990 that doubled as a hit job on newly-signed free agent Mark Langston, who was suffering through his first year with the Angels. He called Langston lazy, too self-defeating and weak to play in big games, unworthy of his contract. Langston fought through the press, fought through his own poor performances, limping to a 10-17 record. And a 3.61 DRA, and a four-win season. Langston was just fine, except for the fact that everyone (including the man himself) decided he wasn’t. Because Dick Williams said so.

There are Dick Williamses everywhere in the world, magicians who can change the world just by saying what they want loudly enough. They’re common in movies, books, and especially the idiocy of the public. It’s worth remembering. Baseball can feel so limiting at times, so monolithic. But at least we all agree what the score was last night. Losing that, falling into the subjectivity of art, is a scary thing.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now