When Christian Stephen Yelich, his oak tree strength forged in, fittingly enough, Thousand Oaks, California, hit another towering home run, or dinger, or tater, first coined as another word for home run by Phernum Terance “Sleepy” Rosewater in a Somerville, Tennessee Taco Bell in 1971, despite the fast food establishment never serving tater tots, according to two people familiar with the situation, Bernard “Bernie” Brewer, the longtime mascot of the Milwaukee Brewers, originally known as the Seattle Pilots for just one season before they moved closer within America to be closer to its heart, at least geographically speaking, Bernie Brewer, himself a caricature of a real human being with hopes and dreams named Milt Mason, slid down his plastic yellow slide in glee, a slide with a decidedly convoluted and arbitrary path towards its destination, not unlike the Northern State Parkway, a grand achievement unquestionably, but all the same not originally intended to so abruptly and conveniently bend away from rich man Otto Kahn’s private golf course, yet Robert Moses, who tried to hide it from me, Robert Freaking Caro, acquiesced to the “robber barons” of old New York, lying to you and me and all of the vape clowns out there in the city today, lying, like Cody James Bellinger, son of Clayton Daniel Bellinger, a liar after swatting majestic home runs himself, an implicit promise to the Milwaukee faithful he was simply a young man on a mission to smack a baseball, defense only extracurricular, as if he were Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the baseball, made of cork, gray wool, cowhide, and lord knows what anymore, not even I know, like it was Robert Francis “Bobby” Kennedy, a violent collision course meant to be, Bellinger the Younger’s hatred of the baseball so complete, the jealousy understandably fully ignored of Christian Yelich’s popularity, yet immediately understood on Sunday when he robbed Yelich of a home run, flat out stole it like it was the 1948 Texas Senatorial election and he was Lyndon Johnson, and there stood Yelich, a stand-in not for a Saturday Night Live star but poor Coke Robert Stevenson, determined to not become Coke Stevenson, but the Pepsi, the LBJ, who had a button in the Oval Office he would press for Fresca, a Coca-Cola product actually, but that’s neither here nor there, Yelich is determined to be LBJ, not the LBJ in my fifth book where he royally mucks up Vietnam and makes weirdass calls to Haggar pants, which I will finish, please stop asking me when I will die, but the LBJ in my fourth book, the good LBJ, the good CSY, the good MVP.

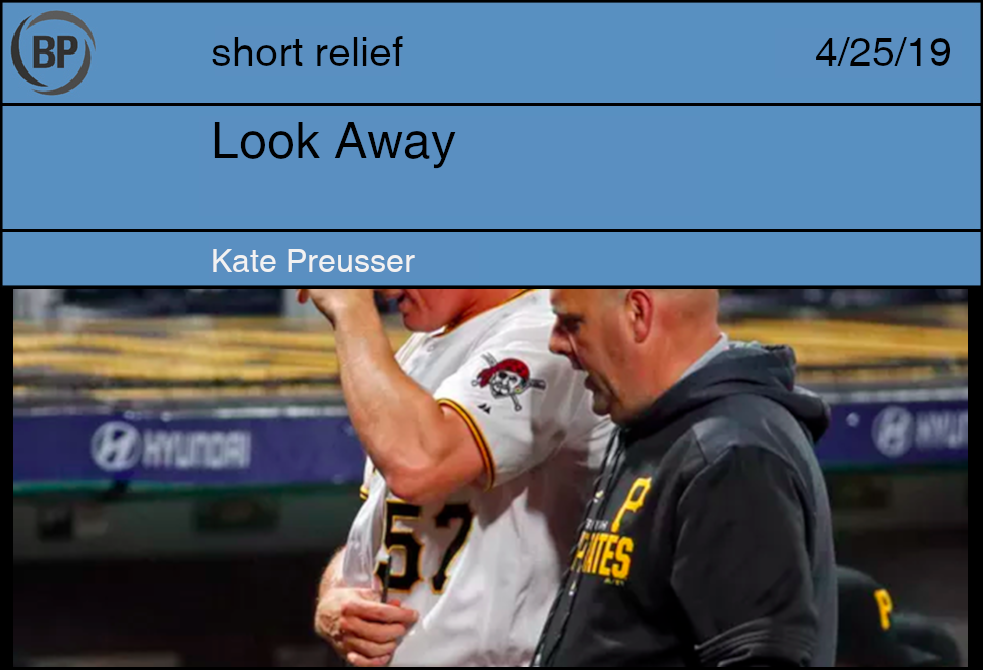

I was leaving a restaurant with friends when I saw Nick Burdi crumple to the ground. The two of them are baseball people, too, but even if they hadn’t been, I feel we all would have been arrested by the moment of watching Burdi grab his arm and writhe in agony, tears streaming down his face. “Stop showing his face,” I pleaded with no one, but the camera remained fixed on Burdi, heaped on the mound, his shoulders heaving with silent sobs. The three of us stood there for a moment, half-into our coats, amid the thundering background music and chatter and fork-clank of the taco joint. We couldn’t look away.

Burdi has the kind of story you can’t help but root for: a second-round draft choice in 2014 who was an elite college closer, he ascended through the Twins’ system before running into some injury trouble in 2016, missing time with an elbow bruise and then the dreaded Tommy John. The Phillies took him in 2017’s Rule 5 draft, while he was still recovering from TJ, and then flipped him to the Pirates. Finally, after two and a half years of rehab, Burdi made his major league debut last September. He pitched in two games to an ERA of over 20, but he was so delighted to finally get a shot at the big leagues, he didn’t care. Besides, he knew he wasn’t those 1.1 innings of work.

This spring, Burdi showed the overpowering stuff that made him a third-round draft pick, striking out 13 batters in 10 innings. His fastball flirts with triple digits; his slider dives off the plate at the last minute like a bird of prey. He continued that hot start into the season, posting elite strikeout numbers: 17 in just 8.2 innings. After years of struggle, Nick Burdi’s moment had arrived.

And then, agony.

When you search Nick Burdi’s name, what comes up isn’t this video of his running fastball or the time he got the Pitching Ninja treatment; it’s the terrible moment of his injury, of course, because moments like that call to us on a cellular level. Reflected in Burdi’s face is an anguish most of us have felt at some point in our lives, physically or emotionally. It feels grotesque, invasive to look at, and yet it’s impossible to look away. The camera cannot stop showing his face.

In moments of agony, most of us do not have hundreds of cameras trained on our faces; our experience of the face of pain is mostly through a mirror, watching others undergo pain. Sports injuries are different, as well; unlike the movies, there’s part of us that knows sports injuries are real. The pain isn’t being interpreted or translated but directly experienced. In our brains, empathetic pain is processed along the same pathways engaged during the first-hand experience of pain. It’s physically painful to watch.

But most of us do watch; one video of the injury has 65 thousand views. The curiosity, or appetite for knowledge, is that great. It’s also a reminder that this pain may one day be yours, but it’s not, now; for now, you can watch from a safe distance.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now