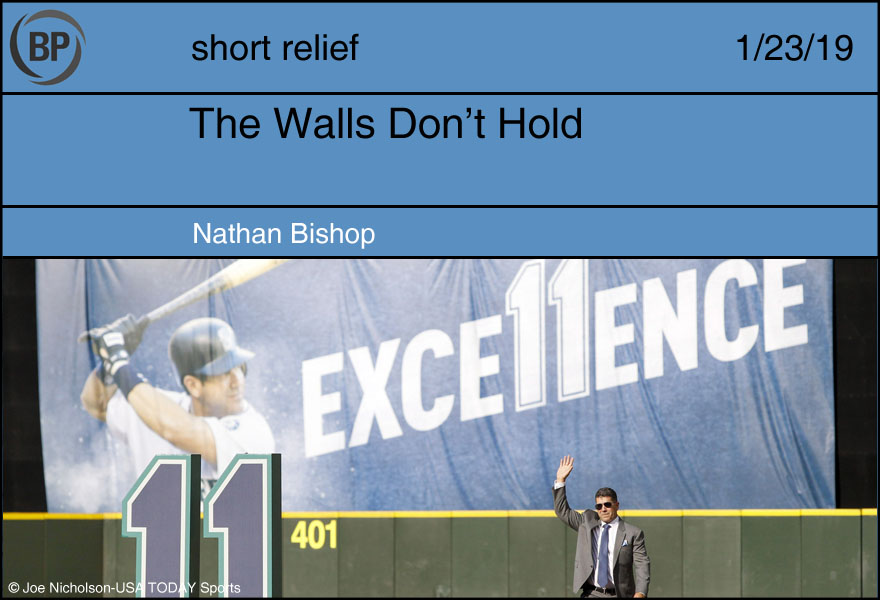

Walls are in the news, and walls are on my mind. Today, as I write this, or yesterday, as you read this, Edgar Martinez was elected to the baseball hall of fame. Edgar had many walls placed in front of him throughout his career, and one was named Jim Presley, who stood tall and solid at third base in Seattle in the late 80’s. Despite Edgar hitting .329, .363, and .345 in Triple-A from 1987-1989 (as an amusingly on-the-nose-for-purposes-of-this-metaphor Calgary Cannon), Presley and his mid-600’s OPS were seemingly unbreachable. It wasn’t until 1990, when Edgar was 27, that he was finally allowed to play everyday in the major leagues. He hit .302/.397/.433. It would be his worst full offensive season until his very last, 15 seasons later.

Edgar’s own body built walls against him, too. He suffers from an eyesight disorder called strabismus, which prevents his eyes from working together. Martinez dedicated himself to eye exercises, avoided screens like the devil they are, and played at a Hall of Fame level through the age of 40. For Edgar, walls were nothing but double-catchers, the collectors and organizers of his many line drives.

After his playing days the stigma of Edgar’s position, his quiet nature, and lifetime membership in baseball’s witness protection program–The Seattle Mariners–combined to brick and mortar a seemingly insurmountable obstacle between Martinez and the Hall of Fame, and it is here that I, like Edgar, found myself stuck. Walls do many things, but first and foremost they separate things, space, and people from each other. Edgar’s separation from Cooperstown, where he belongs, ate at me in that dumb, fickle, poisonous way that unimportant injustices do. I became embittered, my mind closed upon that injustice, and in so closing became a sort of wall of its own. No other players were good enough. Every inductee, every great career was a new target for me to mentally pepper with holes through which I hoped Edgar could climb through to his rightful place.

I’m grateful that, as Edgar’s vote totals climbed along with my age, I was able to grasp some perspective. I’d taken a cause for a good man with a worthwhile case, and turned it into something negative, something hurtful, something that became more about me than what was right. I’d encased myself in a fortress of facts, and in so doing made myself all kinds of miserable. Fortunately for me, and for Edgar, no walls last. Eventually, they always crumble. The crumbling is the best part, I think. That and the speech, in a sunny field in upstate New York, with friends and family all around, without a single wall in sight.

I am the mystery team.

Am I the Marlins? The Phillies? The Mariners? Yes. I am the cloaked stranger in the night, arriving at your door. My motives are unknown; my actions are undetectable; my identity has flummoxed authorities. A player believes he has all the offers on the table, until a knock arrives during a stormy winter’s eve, and my hand extends to him a contract so realistic, so considerable, that he has no choice but to contemplate it. And before he can ask who I am, I morph into a murder of crows and take flight into the darkening skies.

Free agency has come to be a gentle pursuit of talent; a gentleman’s contest between suit-and-ties on other ends of a phone. They chortle about the weather before volleying millions back and forth between themselves and a desired player, then go out for martinis on the town. Little do they know, as they slurp their cocktails, that pure anarchy has found its way into their painstakingly constructed deals, by way of me.

My offers are relentless and clandestine, typically the ideal numbers for which my targets are looking. Barely detectable by those whose job is to know things, I can be referred to only as a “mystery team,” their desperate pleas for greater knowledge met only by my sinister laugh from the shadows and the swirling of my cape from the fire escape. Only after the ink is dry does a player’s disappointment register, as they see the bills handed to them feature not the images of actual American currency, but rather the mysterious question marks that serve as my calling card. My high-pitched cackle echoes off the walls as I disappear into the night before they can even confusingly ask: “What the **** is this?”

I am the bane of free agency; I am the chaos of three-team trades. The front office of your favorite team has almost certainly worked agonizingly on a deal, only to learn of my involvement and grown truly exasperated. Was I the union electrician in Philadelphia? Was I inside the ATM Machado walked past in Chicago? Was I the chauffeur that drove him 85 blocks in New York? Who knows? It will have to remain… a mystery.

“The ‘mystery team?’” MLB GMs ask. “That guy who shows up wearing a crude recreation of Heath Ledger’s makeup in The Dark Knight and screws up all our deals by being weird? He’s like Marlins Man, but like a millions time worse worse.” They may roll their eyes and sigh audibly, but both they and I know the truth: That I am a master saboteur, I am everywhere at once, and, as my haunting high school yearbook quote read, “Some men just want to watch the world burn.”

A-HAHAHAHAHAHA

The best part about this summer’s Hall of Fame ceremonies is going to be watching Mariano Rivera and Jim Thome start a brawl over who’s hugged more sick kids. While Mariano’s unanimous election is getting justifiable nationwide publicity, it’s just as rare that the two nicest players in the last three decades are being inducted in back to back years. Rivera and Thome sound less like a pitcher/hitter confrontation and more like the final battle to become Highlander of Kindness. Two all-time legends whose shared existence seems to say “Get bent, Leo Durocher.” Except there’s a 100 percent chance both of them would make sure to say “Please.”

If you were to break the Hall of Fame roster down, it’s filled with plenty of decent people. But if you were to only look at the personality extremes, the good guys are way outnumbered by the combination of taciturn grumps, alpha male jagbags, and borderline sociopaths (Hi, Ty!). It probably has something to do with a profession based entirely on attempting to defeat your co-workers 162 days a year.

To be sure, the nicest guys in Cooperstown are justifiably celebrated. Stan Musial’s recent biography makes a compelling case that they picked the wrong guy to be Dalai Lama. Ernie Banks could find the bright side of even the most depressing predicament of all: playing on the 1950s Cubs. And Harmon Killebrew once tried to explain his “Killer” nickname by saying “I didn’t have evil intentions but I guess I did have power.” Killebrew was nice to the point where his own nickname worried him so much that he had to tell the media he wasn’t actually homicidal. This just doesn’t happen in baseball. Chipper Jones never had to call a press conference to announce, “Contrary to what you might be thinking, nobody ever fed Steve Buscemi’s lifeless body through me.”

So as you might expect, it’s rarer still to find Hall of Famers with the Rivera/Thome level of kindness inducted so closely together. There’s only one comparable pairing that I can think of and it took place in the Hall of Fame’s first ballot when Christy Mathewson and Walter Johnson were elected in 1936.

The Big Train was so beloved in his time that one of his World Series losses produced the headline: “McGraw Sorry for Johnson, Wishes Veteran Hurler Could Have Won Game” after that loss put McGraw’s Giants one win away from a world championship. Mathewson, meanwhile, was considered such a role model that he was nicknamed “The Christian Gentleman.” Which should make everyone glad he played before the days of John Sterling (“Judge tells The Christian Gentleman’s fastball, ‘Give us Barabbas!’”).

It’s pretty impressive that you have to go all the way back to the Hall’s first class to find two players as nice as Rivera and Thome. And the only way the Hall could exceed that combined level of kindness would be a year where Buck O’Neil was elected by himself.

Sigh.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now