It would make sense to extend the netting completely across the ballpark, and maybe just have the ballpark covered in plexiglass with holes for the athletes to breathe. Because in the end we really treat athletes as zoo animals: creatures to observe, admire, and fervently believe that they are not us. Getting money to play sports? Try navigating a companywide reply-all email chain, muscleheads.

And we know this in the back of our heads, but it helps to be reminded that the vast majority of athletes retire before they reach their goals and have to re-enter our workforce, leaving their statistics frozen in perpetuity across a number of databases. Their life story continues very much away from the spotlight. There are exceptions, such as when I just wonder what Deik Scram is up to.

Deik Scram played in the Tigers system a few years ago. He topped out with a couple of seasons in Triple-A. He once hit 20 home runs in Double-A. He was mentioned in two different Annuals, mostly because his name, you may have noticed, is Deik Scram. He was, as they say in the business, an org guy.

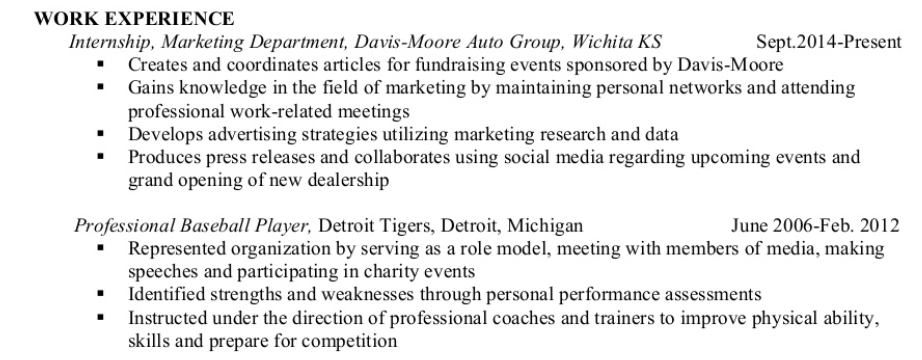

Maybe at some point B-R will get the funds to start publishing rows highlighting their non-baseball occupation in each season, but for now we’ll use the next best resource — and that’s not saying much — LinkedIn. After Scram was released in 2012, he got his college degree and today works in commercial auto sales. I was curious to see if his resume included his baseball career, because why would you not mention it?

I have never seen the job description of a baseball player described thusly. I suppose it would be redundant to mention that it was his job to spearhead initiatives to move batted balls into creative spaces unoccupied by other baseball players wearing different jerseys. Or to collaborate with team members on catching baseballs that opponents hit. And to maximize body velocity across four different baselines.

There is a skills page. It did not mention bat speed or glovework. There was a awards section, and it did mention his Player of the Month honors alongside making the dean’s list. Now that I think about it, I’m definitely updating my resume to include my World Curling Ranking (currently: 367). It will definitely be relevant in my next interview.

July 15, 2019 – OAKLAND (CA)

The baseball world is buzzing as it appears for the second-straight year, the Oakland A’s first round pick will not become a member of their farm system. 29th-overall pick Jurgis Rudkus informed the club he will decline a contract offer to pursue opportunities in the meatpacking industry.

The Lithuanian-born Rudkus was considered raw by scouts but seen as toolsy enough to potentially be a steal for the roughly $2.4 million in slot value if he hit his ceiling. But the immediate opportunity for a full-time role on an industrial killing floor proved too tempting to pass up for him. Brown’s Slaughterhouse is the favorite to secure Rudkus’ services, though Durham’s Fertilizer Plant was also previously in the mix. At least one mystery meatpacking plant is believed to have also made an offer.

Despite a cool market for free agents the past few years and teams’ increasing tendency to non-tender players in an attempt to avoid raises on the scale dictated by the arbitration process, life as a major league regular is still viewed favorably compared to the meatpacking industry. But despite likely needing to exhaust his resources to afford the down payment on a slum battered with fumes from the nearby Brown’s slaughterhouse, sources say Rudkus is believed to prefer this path over the prospect of the minor league grind, which would have likely begin with a stint as a Vermont Lake Monster in the short-season New York Penn-League.

“Centennial Field is like, really old,” the source conceded. “And next to a creepy woods. I wouldn’t be signing up to die in an industrial accident either, but I get the hesitance to not sign up for showers that don’t always work and per diems only large enough to buy Wal-Mart rotisserie chickens.”

Rudkus has been a regular and increasingly vocal presence at socialist labor organizing meetings in recent weeks and many believe that sentiment would be more welcome on the factory floor than with the MLBPA. But with the decline in union participation still a general trend across the American workforce, baseball is still likely to win over candidates who would otherwise be tempted by the amateur circus industry, bowling alley custodian work and toenail clipping disposal services.

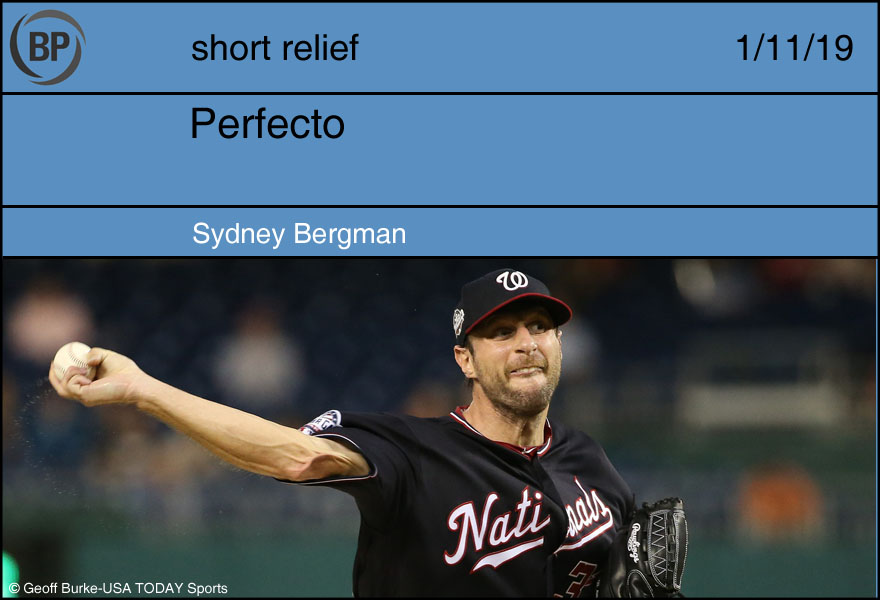

I watched Max Scherzer’s second 2015 no-hitter, which I’d never seen before, on New Year’s Eve day. Though the game sat on my DVR long enough to metaphorically gather dust, I couldn’t immediately remember why I hadn’t ever watched it.

What had I been doing that night in October 2015 in the lackluster last days of the Matt Williams era, when Max Scherzer pitched perhaps the most dominant game of his career, even as the Mets were going to the postseason and the Nationals were going to the long, dry offseason? Watching Matt Damon scratch potatoes from Martian dirt, and turning my phone back on after the movie to a string of texts proclaiming that something was happening.

But the no-hitter wasn’t a perfect game because of a throwing error by Yunel Escobar that allowed a baserunner, a routine toss across the diamond that Escobar managed to bobble. The second perfect game in an imperfect season interrupted by something beyond Scherzer’s immediate control, the first being a perfecto diminished to a no-no by José Tábata’s elbow-first HBP. Watching the game, even in hindsight, felt initially deflating. How close had Scherzer come to perfection, only to be denied by a throwing error from a player who had 145 errors over 11 seasons?

It felt right to be reminded of the impossibility of perfection just before New Year’s, when people resolve to become our more perfect selves. I’m not a huge New Year’s resolutions person, in part because I’ve spent long enough on an academic calendar that August, and not January, still feels like the beginning of the year. And in part because I know the exponential decay curve of my own resolutions, to be done with great and then rapidly waning enthusiasm. That my resolve usually lasts three days at most, and then I go back to whatever habit I’m trying to break. It’s a cliche that perfect is the enemy of good, that perfectionists are prone to indecision, a constant thrumming what-if that freezes action.

And that’s what kills resolutions or really any big substantive change – that feeling that anything short of perfection is, in essence, failure. If I pledge to go to the gym, or read more, or clean the garage, or call my mother, and don’t do so with the regularity and enthusiasm I’ve promised myself, then I’ve failed.

But here’s the thing about excellence: It often comes dressed as marred perfection. A slightly imperfect game can still earn a game score of 97. The world can elbow its way into your plans to be better than your past self, but that doesn’t make those resolutions not worth making or doing, so long so you can learn to live with, if not perfect, at least pretty damn good. Maybe that should be my resolution after all.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now