“Is this it?”

Your friend walks up and stands beside you. “Yup.”

You look, aghast, at the immense pit of mud and fencing in front of you. Though the fencing separates you and the pit, as you continue to stare at it, you feel like it’s expanding, like it might swallow you up at any moment.

You shake your head violently. “No way. No.”

Your friend sighs. “Unfortunately, yes.” They frown at the darkening sky. “Now can we please go back? I don’t want to get stuck out here in the dark.”

You barely hear them. You are staring into the pit, trying to visualize in its ugliness the place that it used to be. The little swing set and the patch of hard sand. The see-saw that had been broken as long as you could remember. The brick wall that you used to throw baseballs against. Your dad always hated that, because you scuffed all your baseballs to hell as soon as you got them. He kept having to buy new ones. You just kept throwing them against that brick wall. There was no more reliable companion to play catch with.

Your friend taps you on the shoulder. “Hello? You still there?”

“Yeah.” You turn to them. “Do you know—what are they going to build here? Are they building another park?”

They laugh. “Nah, dude, there’re barely any kids left in this neighborhood. This is gonna be, like, condos.” They take a few steps down the path, as if to lead you along. “Or maybe some kind of shopping complex? I have no idea. It’s gonna be something big, though.”

You once got a special glove for Christmas, the only time you actually got what you asked for. You had to have been around six or seven. It had some player’s autograph on it, some player who you idolized at the time and who ended up not being all that great. The best thing about it was that it was blue. It had white trim. You thought it was the coolest, most beautiful thing you’d ever seen. You refused to take it off, carrying it with you constantly, and your dad scoffed and said you would lose it, and you swore on your life you wouldn’t.

You lost it by the end of January. You kept looking for it until next Christmas. You combed every inch of the park fifty times over—you must have left it at the park, there was no other place you would have taken it. You made missing posters. You never saw it again.

“When did this happen?” you ask your friend.

“At least a year ago. Or maybe more? Who knows, honestly. I think the development got stalled for some reason.” They start heading back down the path. “Come on, I don’t have an umbrella.”

“They just left it like this?”

Your friend, without turning around, raises their hands in a gesture of futility.

“You’ve been gone for a long time,” they say. “I honestly don’t know why you came back. There’s nothing here.”

They disappear into the trees. You turn back and stare into the pit again one last time. In the dying light, you could almost swear you see a flash of something blue, down at the bottom of the pit, far beyond your reach.

When the sun came up on Puerto Rico on New Year’s Day, 1972, it rose on the citizens of the island already awake, lining the island beaches. They carried transistor radios and lights and babies, and they carried something much heavier, heavy the way impossible things are heavy: their disbelief. Clemente was a god, and what god could fell Clemente? They studied the blue expanse before them, calling out to one another, and patiently waited for their hero to walk out of the sea.

In the book of Matthew, Jesus sends his disciples out on a boat. The waters are turbulent and the disciples become afraid but then Jesus appears, walking on the water, and tells them to be not afraid; tells them, in fact, to be of good cheer. The disciples struggle, a little, to let go of their fear; they have to be shown that in the midst of the storm Jesus can still deliver them to safety. That’s how things are, in the storm–it’s hard to see out of. It’s hard to imagine, in the middle of a storm, that there will ever be another time, a not-storming time, even if you know from previous experience that the storm will pass eventually. But what if. What if this is the time it doesn’t? What if this is the time everything is pulled away? A measure of faith is necessary.

So the citizens of Puerto Rico, devout as many of them are, stood on Piñones Beach and tried not to be afraid, to have faith. The waters were dark, storm-tossed and shark-infested, and still, still they believed he would walk out of the sea.

My uncle Carl was built like Clemente, with the same movie-star good looks, all barrel chest and broad shoulders tapering to a narrow waist, with biceps the size of the fenders he tossed over the side of his boat. He looked like a 19th century stevedore but was a man of great faith and greater tenderness. He also spoke in a soft voice, in the way that certain men, men of great power and confidence, do; men who know they don’t need to shout. It took an especially aggressive form of cancer to fell him, and yet we all sat with him, day after day, expecting the disease to change course, for the cancer to realize what it was dealing with; we expected him to walk out of the sea. At his memorial service the choir sung Be Not Afraid, but I was, and still am, terrifically afraid of the forces that can cut down the men we know as gods, and in mourning for the loss of people like Clemente, and my uncle, and the others like them lost in a storm where we are still, over 100 days later, struggling to calculate the toll of loss. There are so many of us standing on those darkened beaches, hoping to see a sign, taking whatever comfort we can in the fact that at least the sun will rise, trying our best to look through the storm to find a measure of faith.

This June, like every other June, a group of people will stand on the beaches in Puerto Rico and walk backwards into the sea. They will dunk their heads beneath the water and ask for forgiveness for their past sins, to walk forward with a pure, clean heart. They will ask for change, and some of them will be granted this wish. They will walk out of the water, intent on living their lives a little better, a little more like the man who worked for the betterment of all people regardless of who they were, a man who called Puerto Rico home, who was called home there again.

On Wednesday, September 5, 2018 A.D., 23 year-old Ryan John “Rowdy” Tellez made his major league debut in the eighth inning of a Tampa Bay Rays-Toronto Blue Jays showdown at the Rogers Centre.

John Gibbons, Blue Jays manager (2004-2008, 2013-2018): What you have to remember is most names are boring. Wait a minute: why does this say “2013-2018“? I haven’t been told this is my last season. Do you know something I don’t?

Curtis Granderson, former Blue Jay, current Milwaukee Brewer: When I heard Rowdy got into a game, I was immediately furious that the Blue Jays traded me. Rowdy was literally the only reason why I signed with Toronto in the first place. I’m ashamed to admit I think I frowned at a teenager that night.

Vladimir Guerrero Jr., top Blue Jays and MLB prospect: Rowdy doubled in his first at-bat, off of the first pitch. I’m sure it was cool. I didn’t watch. I was too busy still not promoted to the big leagues for poppycock reasons.

In Rowdy’s starting debut the next evening against the Cleveland Indians, Tellez went 3 for 4. All three of his hits were doubles. He became the first player in the live-ball era to record extra-base hits in each of his first three career plate appearances, and the first with four or more XBHs in his first five.

Randal Grichuk, Blue Jays right fielder: They should have sent a poet.

T.S. Eliot, deceased poet: It is always neat to see a young man start his baseball career with a whizbang like that.

His Eminence Ferdinand “Rowdy” Ferguson, the first guy to accidentally have sex in the Skydome hotel with Blue Jays fans watching: Please stop calling me for quotes.

The next night, Tellez went 2 for 5. Yes, both of those hits were doubles.

Carlos Carrasco, Cleveland starting pitcher: I served up both of those doubles. No shame in that. The guy ended racism.

T.S. Eliot: #Actually, I think Cleveland didn’t wear Chief Yahoo on their sleeve during that series for some Canadian reason.

Carlos Carrasco: Ended. Racism.

Bean Stringfellow, actual former baseball player and agent: Rowdy Tellez is a silly name.

On Saturday night, Tellez did not double: he homered. Rowdy also hit his first major league single. It made him the first player since at least 1908 to hit for extra bases seven times or more in his first four major league games.

Mike Trout, Angels outfielder: It turns out I’m a walking pile of hot garbage. Good to know.

Bob Woodward, author: A person familiar with his thinking says Binghamton Rumble Ponies mascot Rowdy the Pony is very proud of his namesake. Same goes for Rowdy, the dog from Scrubs.

Rowderick Rembrandt, Blue Jays season ticket holder since 1985: I wish we didn’t have to wait so long for Rowdy. This dumb wasteland of a franchise. Indeed, April is the crullest month.

T.S. Eliot: Very funny.

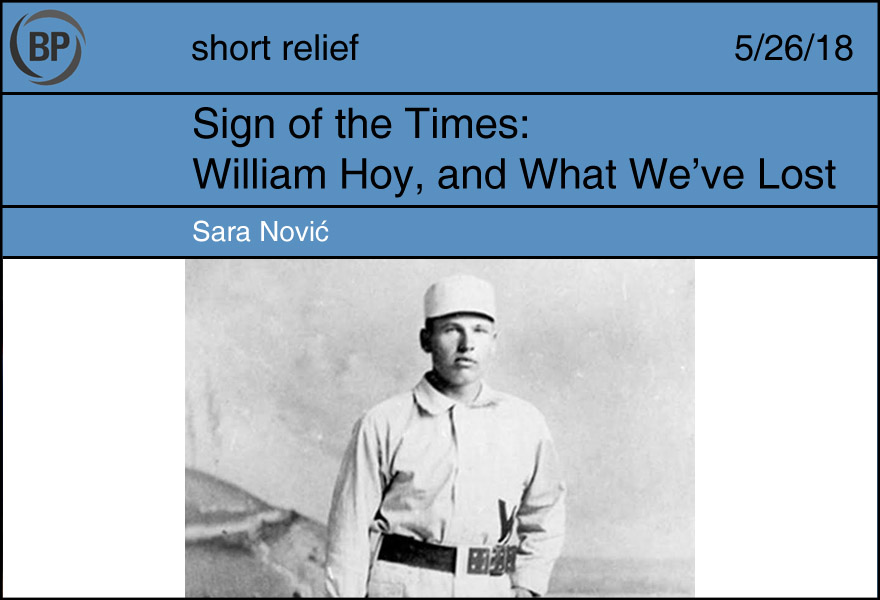

This Wednesday the 23rd was the 156th anniversary of William Ellsworth Hoy’s birth. Hoy is widely recognized as the best Deaf baseball player in MLB history.

Born in Ohio in 1862, Hoy lost his hearing via meningitis at age 3. Bright and motivated, he enrolled at the Ohio School for the Deaf at age 10 and graduated at 16 as the valedictorian. In the 19th century, most deaf people were trained vocationally, and Hoy learned shoe repair and had his own shop within a few years. He played neighborhood baseball on the weekends or the slow summer season, and was spotted by a scout, Natural-style, who invited him to join the Kenton, Ohio team. From there, he left home and joined the Northwest League.

Hoy, thin and 5’6” at best, had little power behind his bat. Worse, he was distracted at the plate, where he struggled to discern whether the umpire had called a ball or strike. Legend has it that Hoy requested of his Northwest League manager that the third base coach signal balls and strikes so he could follow along. The manager obliged, and Hoy hit over .300 the next two seasons. It’s still debated whether Hoy’s request was the impetus for the signals umpires used today.

“Dummy” (ugh) Hoy made his major league debut in 1888 and played for seven teams across his 14 years. His best seasons were with the Reds, 1894-97 and 1902, where he slashed an average .293/.392/.402 with 176 stolen bases (he’d steal 594 across his career). As the steals suggest, Hoy was fast and played centerfield shallow, which, combined with his good arm, meant he racked up putouts and assists, once throwing three runners out at home plate in a single game. Since he couldn’t hear calls from the other fielders, they deferred to him—he’d yell out if he had it and say nothing if he didn’t. Tommy Leach, Hoy’s roommate and fellow outfielder in Louisville, said many of his teammates also learned basic sign to communicate with Hoy.

But perhaps the most intriguing part of Hoy’s story is that, at the time of his debut, he wasn’t the only Deaf player in the Major leagues—there were two others playing at the time, and several more on the books. Hoy even went up against Deaf Giants pitcher Luther Haden Taylor, the only such matchup in MLB history, in 1902. Hoy and Taylor are said to have chatted briefly in sign before retaking their positions.

People often think progress means life is automatically better for d/Deaf and disabled people. And in some sense, it’s true—I mean no one’s walking around calling me “Dummy.” But with progress, especially in technological developments, comes a change in cultural attitudes—if the deaf person can be “fixed” it follows that they should be, and it’s no longer the majority’s responsibility to make an effort to communicate in a way that’s mutually accessible. It’s difficult to imagine my coworkers changing their everyday habits to make things easier for me, or taking time out to learn ASL. Our education system glorifies “mainstreaming” as integration, but in reality, the goals set for deaf children are more about blending in, endlessly practicing to speak and listen when that energy might be put toward other skills.

I think often of the talented people that are lost this way. It doesn’t seem a coincidence that we haven’t seen a culturally Deaf, ASL-using player on the major league field since Hoy, age 99, threw out the first pitch at Game 6 of the 1961 World Series.

I hope I’m wrong, and that the next great Deaf player is just around the corner, ready to be a role model for those kids seeking validation in their own language, culture, existence. Until then, I’ll keep rooting for Hoy—Cooperstown or bust.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now