1.

The crows complaining from the maple tree outside the window sound enough like that one row of fans in Philadelphia in 2006, Mike Lieberthal at the plate in the second game of the September 3 double-header against Atlanta, the one that isn’t the one where Ryan Howard hit three home runs. Lieberthal stands in for what will be his only plate appearance of the day, nearing the end of a season in which he plays just 67 games, the penultimate season of his career.

“Ah!” one of the murder jeers as Lieberthal takes a warm-up cut. “My back, my back!”

Lieberthal sends the ball skimming safely through the infield, one of just five Phillies hits in the nightcap. It’s morning where I am. Something falls from the tree—a twig, a knot of maple keys—and in my memory, two of the men stand up, clap loudly.

“Good job, Mike!” one caws.

2.

The belted kingfisher is a bird crested and caped in slate blue and banded in white across the breast. An adult belted kingfisher weighs between four and six ounces. It is not inaccurate to say a belted kingfisher weighs about as much as a baseball.

They fish from rocks and branches and posts overlooking the water, heads craned down, and when they spy their prey—minnows, crayfish—they plunge, headlong, into the water. For an instant, bird and its object disappear, only to emerge, ungainly, flapping to a sturdy perch, triumphant. The flecks of water shed from its wings turn as white as popcorn in sunlight.

The belted kingfisher, were it a creature with hands and bigger than the baseball itself, would make an excellent third baseman.

3.

From the row of Adirondack chairs, this is what’s visible: the river’s liquid fence, the gallery’s trim infield, the bridge’s concrete gray like stadiums I’ve known. Red paint flakes from the wood and sticks to the back of the thigh with midsummer humidity; ants patrol the fine-grained earth the same way they do the crabgrassed outfields of a thousand sandlot parks. Behind a shed, something cracks, a solid, wooden sound—maybe one of the sculptors making adjustments, maybe someone local, readying for fall. Sometimes a logging truck rolls by. At a distance, it might sound like applause.

My son, age 10, looked up from his video game. “Wait, they aren’t letting King Felix start anymore?”

***

Once we reach a certain age, society allows us to ponder our mortality out loud. Too young, and we draw the concern and chastisement of our elders. Too old, and we’re perceived as giving up. Around life’s middle bits, however, we can settle in, and publicly consider what it means that we all invariably end.

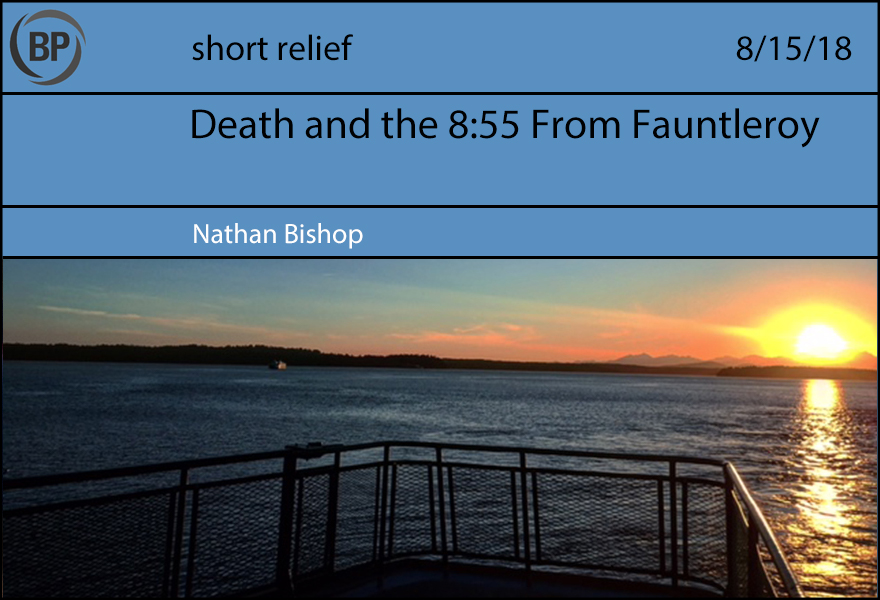

I was on the ferry, at dusk, alone. The day’s heat was actively breaking, and a cool marine breeze was gently cleaning everything it touched. I stood outside, watching the light slowly fade, and thought about death.

Natural beauty, the passing of seasons, years, millenia, and eons have always brought comfort to me when considering death. Observing a day’s passing on the Puget Sound, the rust peeking through caked on paint on the salt-worn ferry, the crystal blue sky’s descent into the fiery horizon, I let my mind wander.

I thought of the first man to push out a skiff into this water, and seeing what I was seeing. I thought of the time before man, when the sounds of the gloaming would have been pure, raw wildness. I thought of the future, far past my time, and felt a deep longing. In our Age of Disruption, when everything and everyone is seeking a new hack to skip, bypass, enhance, and upgrade life, I felt a resonant, primal need to allow the shorelines, hills, and waters I was viewing to develop how they would undisturbed, by their own means, and terms.

I felt small, and pointless, while also an inescapable, comforting sense that that was ok, because it was true. I felt the lure of death, and the promise of new life with it.

In that moment, briefly, somewhere between Vashon Island and home, I accepted where I was and, though I was in no hurry, where I was going. I was, for a small time, at peace.

***

“Well yeah, buddy. Baseball players get old, even the best ones. At some point you just aren’t good enough anymore.”

“How old is Felix?”

“Thirty-two.”

“Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“How old are you?”

With the end of the Major League Baseball regular season coming on Sunday, this may be my last chance to write about Joe Mauer as an active player (and get paid to do it). As a lifelong Twins fan (who appreciates monetary compensation), I would be a fool not to.

But what is there to say about baseball’s least interesting player? He was a really great catcher for a long time, until head injuries made him a pretty decent first baseman. Now, he’s just acceptable. If he retires, he’ll go out with something like a .306 batting average, more than 125 homers, and more than 2100 hits. He’ll have an MVP award, three Gold Gloves, and five silver sluggers on the wall of his rec room.

But, I mean, that’s it. He didn’t cause controversies. He didn’t make waves. There are fleets of buses under which he never threw a single teammate. He tipped generously and said “please” and “thank you,” and hustled on every ground ball. And he took an eight year, $184 million deal after winning his MVP and couldn’t hit 29 homers every year. For that crime, and for that crime only, some Minnesotans came to hate him.

I don’t pretend to understand those people. Mauer was one of the most valuable players in baseball for six years and was underpaid to do it. Such is the system under which baseball is played. When his time came, he reaped the rewards for his serfdom, again, as is customary. Complaining about that seems like complaining that Winter follows Fall. Dude, we know it does. Every year. Settle down.

Maybe the best way I can think of to describe Joe Mauer, as we look back on his career is to talk about what kind of ballplayer he was not:

He was not a ballplayer like Addison Russell or Jose Reyes, or Roberto Osuna or Aroldis Chapman or Kirby Puckett or any of the other ballplayers who have had domestic violence allegations made against them. Joe Mauer’s personal life was boring. He has a wife and twin daughters. He seems to like them a lot.

He was not a player like Jayson Werth or Matt Bush or Mark Grace or Tony LaRussa. He never got a DUI. I mean, for one thing that would mean that he would have had to drink something stronger than 2% milk, which I refuse to believe he’s ever done. For another, even if he were, I bet Joe was an early adopter of Uber, and then switched to Lyft when supporting Uber became ethically problematic.

He was not a player like Torii Hunter, who started a fight in his own clubhouse. Or a brawl on the field. Joe just seemed to want everybody to be friends.

He was not a player like Barry Bonds or Mark McGwire or Rafael Palmeiro. Not that I’d condemn a player for using PEDs, especially in the climate of the late 1990s and early 2000s, but there has never been any concern that Joe’s accomplishments weren’t his own.

He is a nice man who likes baseball and was very good at it for 15 years.

Other fanbases should be so lucky.

Our house came with rose bushes. We have not done the greatest job caring for them in the years since, which we rationalize away by saying that we prefer a wilder look in our roses, that we don’t want them kempt and orderly. We don’t want roses suitable for grandmother’s tea; we want roses akin to the brambles that try to keep Prince Philip from waking Sleeping Beauty. One result of this benign neglect is that one of the bushes, at the front of the house, began shooting off a horizontal branch or two, making it difficult for us to walk what amounts to a path from our front door into the yard. (It’s not really a path, and the slope makes it even less so. I once took a tumble trying to bring my cat home. I kept possession of the cat all the way to the ground.) Nothing had ever bloomed on that branch until a few days ago, and only then did we realize that the color of the bloom (dark red) did not match the bush (pink) we had believed was the source of this branch. Instead, this was a volunteer offshoot of a nearby climbing rose. Having no trellis or other structure to cling to, it sprays off wildly toward the sidewalk.

In the end, we’re going to have to do something about this branch because at the moment it is a thorny gate preventing me from weedwhacking. But for now, it’s a weird, ungoverned offshoot of something that was once constructed, by human hands, to be the epitome of classical beauty, in the human eyes of a city-dweller. Its resistance to those norms verges on revolution. You simultaneously do and do not want to mess with it. You regret and enjoy its excesses. You wonder “what if I’d spent the last few years taking better care of it?” but do not wonder this in a negative manner, exactly; it is a genuine question in your mind.

And in the end you shrug your shoulders. The past isn’t the point; the future barely is. The present, in its unpredictability and joy and pain, is the point.

In surely unrelated news, Bartolo Colon got awfully close to a perfect game on Sunday night.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now