When Charlie Montoyo was the manager of the Durham Bulls, the Tampa Bay Rays’ Triple-A affiliate, he liked to respond to questions about injured players’ timetables for returning to action with this quip: “He’s day-to-day, and today is not the day.”

It really is true that you gotta play ‘em one day at a time, as another Durham baseball sage put it. During Montoyo’s eight-season managerial tenure with the Bulls (2007-2014), he professed never to know his team’s record or exact place in the standings until around the final week or two of the season. He would put his palms over his ears if someone tried to tell him.

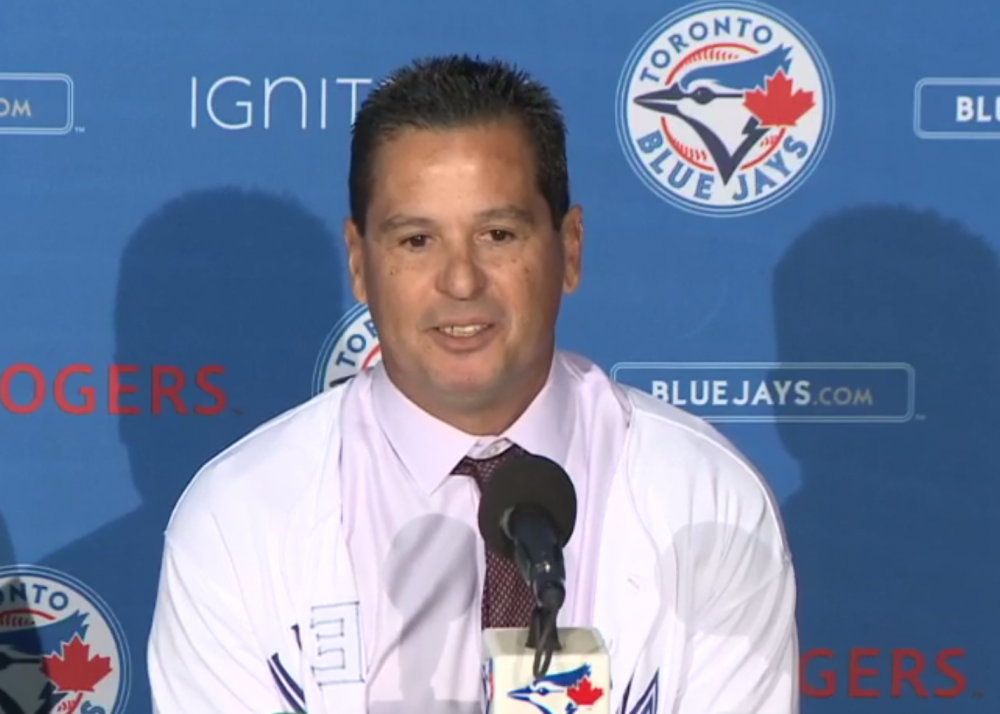

That isn’t to say he didn’t care about winning. He did and does, strongly and deeply. The evidence of that was clear at Montoyo’s introductory press conference with the Toronto Blue Jays, who hired him to be their new major-league manager last month, when he responded to a reporter’s suggestion that he was taking over the helm of a losing team in 2019. “Really?” he snapped back. “I don’t think that way. We’re going to play to win from the beginning.” He always did in Durham. His Bulls made the playoffs in all but one of his eight seasons, won two championships, and came within a strike of winning a third. (His last Double-A team, the year before he took over in Durham, also won its league championship.)

The measure of his commitment to winning: the only time I ever saw Montoyo genuinely rattled in his office was when his 2011 team verged on a final-week squandering of a division title they’d already all but clinched. An important thing to know about that team (which ended up securing its lead and its title): its talent wasn’t the best in the division, and it was even more subject to daily upheaval than most Triple-A rosters, its personnel even more motley. Perhaps the most remarkable accomplishment in Montoyo’s consistent success with the Bulls is that he did it in Triple-A, baseball’s most wildly inconsistent milieu.

Montoyo was often asked in Durham about the methods behind his success. He had a line ready for that question, too: “Everybody plays.” He meant it. If a big-league talent had to sit so that an anonymous A-baller keeping a Triple-A locker warm for four days could get onto the field, well, that guy was on the roster today, and by Montoyo’s lights he had as much right to play as anyone else. His democracy was no major innovation, but it was a firm act of inclusion and appreciation in a realm where so many decisions were forced on him (and on all Triple-A managers) by front offices operating a system necessarily stripped of nearly all human considerations.

One sometimes wonders why baseball skippers are called “managers” instead of coaches. Not in Triple-A. It really is managing: managing those radically unstable clubhouses that (barely) contain players from almost every walk of baseball life, from prospects to rejects, scrubs to superstars, outliers to outrages, rehabbers to replacements; managing the long bus trips and bad food and middling money; managing the parent club’s interference (we’re taking tonight’s starter away in case we need him in the bigs, so you’ll have to make do with a bullpen-slop game … never let this new stud reliever pitch two games in a row … your roster will have four catchers for a while … oh and now it has Hideki Matsui). It’s easy to make the case that Triple-A is harder to manage than any other level, including the majors.

Well, the majors may not be harder, but they’re entirely different, and the stakes are higher, of course. Demand not supply. Results not tests. Holding leads, not forts. Montoyo will no longer be able to ignore his team’s record or place in the standings. The big deception of Triple-A is that it only looks like a stepping-stone to the big leagues. In fact, it offers little practical preparation at all, for players or managers or anyone else. Montoyo’s four seasons on the Rays’ big-league coaching staff have surely been better training than his previous eight managing Durham. But he won’t be challenged by the verb associated with his job. He can manage.

You’re probably reading this because you’d like to know how he’s going to do it. We don’t know; he’s never done it before. Here are a few more knowns, though:

- He’s not a sabermetrician. He’s old-school, traditional, risk-averse by disposition. This is not the same as saying he rejects analytics or taking chances. On the contrary. He’s a Rays guy, after all, a manager in that organization from its inception in 1997 (and ipso facto a longtime third-base coach, too, both in the minors and in the big leagues: he’s comfortable making critical decisions on the fly). He is steeped in Tampa Bay’s deeply unorthodox culture. He is not resistant to change, because Triple-A is nothing but change. He listens to the people around him (he’ll definitely rely on his pitching coach), he will likely try anything presented to him as a potentially viable way to win, and he’ll implement it if it works. Anyway, an “opener” is no different from all those bullpen-slop games he had to manage in Triple-A (which is secretly, even unintentionally, the most avant-garde and audacious level of baseball).

- Twenty-two seasons in the same organization: loyal. He’s going to devote himself as a Blue Jay and get with the franchise’s program. Montoyo is a company man, a devout Catholic, and the father of a child who has spent much of his life in hospitals and could have easily not survived. (He has said that the perspective he’s gained from fathering an imperiled child leaves him feeling no pressure in even the most fraught game situations.) Montoyo is someone who respects institutions and authority, and his ego is not a prominent structure in his comportment. After the Rays hired Kevin Cash to be their manager—a younger, less qualified candidate, and with only a scant connection to the Tampa Bay organization—Montoyo quickly and graciously accepted the big-league third base coaching job, and later became Cash’s respectful consiglieri as bench coach.

- Loyal, but he will not be an order-taker. Montoyo has his opinions. He is consistent in his demeanor, sets his own example. Most players will like him. He can accommodate big egos and talents, and encourage role players and aspirers (he was the latter when he played, after all). Handling Triple-A clubhouse diversity and its tendency toward diffusion was part of his job. He admires talent, but he loves hard workers. I’ve seen him get as tightly wound as any manager, but his demeanor isn’t aggressive, and he isn’t a yeller. Maybe he’ll learn to be, if he must, but that’s not his style. He trusts his players.

- Not blindly. I’ve heard him speak candidly and pitilessly on the record about his own players’ bad performances. I’ve heard him say, “If you’re hitting .200 in August, you had a bad year.” If you came to Durham and stunk, he didn’t pretend not to smell it. In the bigs, he knows that guys who don’t produce are in line for benching or demotion, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s because they’re injured or unhappy or misused—although he’ll exploit all the data he has at his disposal to use them well. Still, “no excuses,” as he often said in Durham. Off the record, I’ve heard him speak just as candidly about players whose attitudes or characters he didn’t like. He was never wrong about the ones with whom I’d interacted. He is not naïve and he sizes people up quickly—which means, for one thing, that getting an immediate sense of their character and potential is important to him.

He did that with me. Although I was a baseball adept from early youth and followed the game closely, I had seldom written about it and never intended to do anything like cover a team full time. I originally took the assignment as a mere diversion, frankly, from another writing project, and expected to drop it quickly. But Montoyo made me feel welcome in his office for five or eight minutes after every game in the spring of 2009. His constructive, sanguine attitude in postgame interviews conferred inherent value on the act of simply talking over the ballgame that had just ended: nothing very deep, just good-natured but frank assessment, gently wringing the matter of its usable substance before proceeding. So I kept going to games: a fortnight, then a month.

For a week in mid-May, I was the only reporter in the press box. Another paper had laid theirs off, and a third only sporadically sent one. Montoyo could have justifiably not bothered with postgame interviews: one measly writer, and a greenhorn at that? Better things to do with his time at that hour of the night. But he gamely answered questions and shared additional thoughts unprompted. Everybody plays.

Toward the end of the home stand, David Price pitched his best game of the season to date; he’d be called up to the majors for good soon after. I suggested to Montoyo that Price’s slider had looked especially sharp. (To younger readers: Price used to throw a lot of sliders when he was your age). Montoyo nodded. “And you could tell it was a slider.”

A few minutes later, I thanked Montoyo for his time, as usual, and turned to go. The Bulls were soon to leave for a longish road trip. It seemed like a good time to bring my little baseball diversion to a close and get on with my life. Montoyo said: “I like talking to you. You know your baseball.”

I didn’t really know baseball. I took Montoyo to be telling me that the opportunity to learn was here, and that it would be worth it. I covered his Bulls for the next five years. I never sat him down for a long interview or profiled him at length. I talked with him about a just-ended ballgame for five or 10 minutes a few dozen times a season. There was some off-the-record chitchat that became less guarded and finally very warm over the years; there was having a couple of beers with him in a Buffalo hotel during a Bulls road trip; there was having beers with him again, along with our spouses, when my wife and I passed through Tucson (where the Montoyos live) after his first season as the Rays’ bench coach in 2015. In both cases, he insisted on buying—or I should say, he simply got up and paid without any announcement, no fanfare.

As I said, Montoyo isn’t the demonstrative type, so when in parting he strongly encouraged us to visit the historic Mission San Xavier del Bac, south of Tucson, we made sure to do it. It’s a memorable place. But my happiness for Montoyo rests on the assembled foundation of all those short postgame interviews: taking ‘em one day at a time, their modest but inalienable value unquestioned, their contents uncovered and then trustingly forgotten. That is how you know your baseball.

I didn’t think he’d ever be a major-league manager. Not because he wasn’t qualified—or rather, because the qualifications are so nebulous and mutable that Montoyo’s apparently strong credentials didn’t necessarily mean anything out of context. The qualifications are whatever the front office explains after any given hiring, in order to suit it. And not because he wouldn’t be good at it, either (what exactly constitutes “good at it” anyway?). There simply aren’t many positions open from year to year. The odds are against anyone ever getting the call, especially his first one.

But the main reason I didn’t think Montoyo would land a big-league job was that he didn’t appear to want one. Just two weeks before the Blue Jays hired him, he said: “After everything that’s happened with my son, being a big-league manager isn’t the thing I think about the most in my life. It’s not my dream to be a big-league manager. If it happens, and if it’s right for me and my family, then okay. But it’s not my dream.”

Perhaps there’s a little dissembling there, possibly a gesture related to his instinct to cover his ears against knowing his own team’s record. Maybe a little superstition, too, like talking about a no-hitter. There’s certainly Montoyo’s modesty, which is genuine, and the abiding perspective of a man who knows there are more important things than baseball. But he wouldn’t have taken the Blue Jays’ offer had he not wanted the job, and it’s impossible for me to resist saying how deeply happy his getting it makes me. Day to day, and today is not the day. How satisfying to say of Charlie that today, finally, is.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now