Early last October, I found myself at an intake appointment with a new doctor. At these kinds of appointments, which are supposed to precede long-running doctor-patient relationships, the doctors usually want to get to know you. They make friendly conversation. The new doctor asked me about my hobbies and interests. I like baseball, I told her. She asked me if I was a Blue Jays fan. Yes, I said, sitting there in my Blue Jays hat. She asked me if I had any goals or aspirations in life. I said no, not really, but that I liked writing about baseball, although I wasn’t sure if that qualified as a goal or aspiration if it was something I was already sort of doing.

She seemed excited by this information. She asked about what kind of things I wrote—was I a reporter, or a journalist, or a blogger? I shot down these ideas quickly, but had to pause for a second, trying to figure out how to explain exactly what I did write about. I decided the best illustration was a concrete example. So I gave her a quick summary of a piece I had recently written that I liked, about watching Roy Halladay’s last home start as a Blue Jay. I like writing stories, I explained, about people. Baseball happens to be a good place to find stories about people. I like drawing connections from story to story, person to person, and I thought this Halladay story would draw an implicit connection to the current state of the Jays in September: playing bad baseball, meaningless baseball, while preparing for the likely imminent departure of a franchise icon. In 2009, it was Halladay; in 2017, it was Jose Bautista.

“Bautista?” she said. “I know about him. Everyone says he’s a big mean jerk, and that the Jays are better off with him gone.”

I changed the subject after that.

***

I will admit to not having watched much Mets baseball this year. Not when they were racing out to one of their best starts in franchise history, and not over the past month, when they have skidded all the way down to fourth place in the NL East. And after watching the condensed version of their grueling 14-inning, 7-1 loss to the Cubs on Saturday night, I almost felt like I didn’t even need to watch them for the rest of the season—that there was nothing more I needed to know about the 2018 Mets.

That game, though, brutal as it may have been, reminded me of something that I had somehow managed to forget. It reminded me of the fact that Jose Bautista is a New York Met. That, as a matter of fact, Jose Bautista is still playing baseball. That despite not signing with the Braves on a minor-league deal until April 18, and despite getting cut by the Braves on May 20, he is still out there, starting in a major-league lineup.

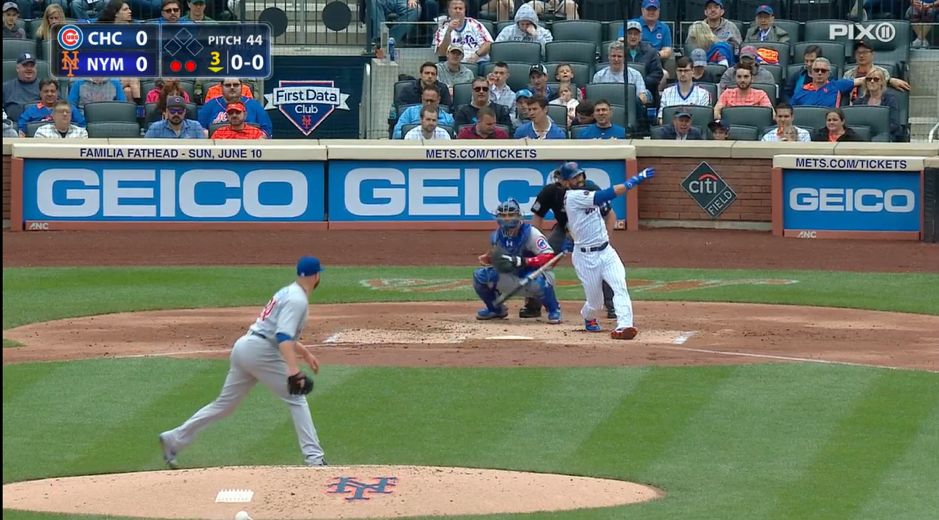

I felt an odd twinge of guilt about how quickly Bautista’s presence had faded from my memory. So I tuned into the final game of the Mets’ series against the Cubs on Sunday. The Mets were on the verge of being swept, and 37-year-old Jose Bautista, with his .209 batting average, was starting at third base, batting second.

***

I am a Jays fan of a fairly recent vintage. I never knew Bautista as a big mean jerk. I never knew him as a struggling utility infielder, either. I jumped onto the Blue Jays bandwagon after my five-season absence in mid-2015, by which point Bautista had always been the Jays’ big hero. He was the central actor in the most incredible baseball moment I’ve ever experienced.

The 2017 incarnation of Bautista, then, was almost shocking. It was a decline both gradual and, somehow, jarringly sudden. The player I was now seeing was so far away from the player that I’d become accustomed to that I had to assume he couldn’t continue much longer. As the season wore on in futility, people talked in increasingly wistful tones about him maybe coming back in 2018, for another year at a discount salary. But that was what people had said before 2017 as well, when Bautista had finally hit the free agent market and found that his services were no longer very highly valued. The 2017 season really seemed like it was the curtain call.

Manager John Gibbons called him off the field in the top of the ninth inning during the Jays’ last home game in September, and as he walked into the dugout, it felt to me like he was walking out of baseball. I couldn’t envision him standing in a batter’s box wearing anything other than a Jays jersey. I resigned myself to never seeing Bautista play baseball again. I said my goodbyes. Bautista didn’t. As the months passed and he continued on, unsigned, he made it very clear that he didn’t just want to continue playing in the major leagues—he was going to play. It was a public commitment to belief in his own skills that I found both enviable and unfathomable.

***

Bautista steps into the box in the first inning with one on and nobody out. He hit .143/.250/.343 in 12 games with the Braves. In 13 games with the Mets, he’s raised that to .209/.346/.388. He wears the no. 11 now, which is bizarre.

What is even more bizarre is how similar everything else feels. The beard, sure, has become slightly less robust. But there are still all the familiar elements—the arms raised, the left foot tilted, ready for that leg kick. He bats second for the Mets; for the Jays in 2015, when I first really watched him, he batted third, sandwiched between Josh Donaldson and Edwin Encarnacion. Now he bats between Brandon Nimmo and Jay Bruce.

Bautista watches two strikes from Jon Lester—one in the heart of the zone, unquestionable, one well-placed on the outside corner. He steps out of the box, grimaces, adjusts his helmet and his pants. I’ve seen it a thousand times. The Bautista whose routine I became accustomed to, though, didn’t strike out in nearly a third of his plate appearances, as this one does. He is behind 0-2. I saw a lot of this last season. I don’t know if I really want to see it anymore.

But he ends up walking. He doesn’t swing at a single one of the six pitches that Lester throws, and he ends up walking. It’s a classic Bautista plate appearance. He trots down to first base.

***

The Citi Field crowd, though reasonably large, isn’t particularly gregarious. The most exciting thing that seems to be happening in the ballpark is the presence of a fursuited mascot, on whom the camera lingers for a weirdly long time. The mascot’s fixed expression is hardly distinguishable from the expressions of the fans who sit around it. The Mets are 2-8 over their last 10 games.

Even this seems familiar: a resigned fan base, a lack of expectation. The Jays, lest we all forget, were a sinking ship in the early 2010s, while Bautista was a perennial All-Star and home run king. True to form, Bautista’s line in his two weeks with the Mets—two weeks during which they have won four games—has been pretty good: .281/.439/.438. His walk rate this season stands at 16 percent; his walk rate in 2015, when he led the league, was 16.5 percent. The plate discipline, the elite eye, one of Bautista’s calling-card skills, is obviously still there, consistent through all of these years. Even last season.

It’s the power that’s not there. Pitches he would have launched two or three seasons ago are swings and misses or desperate foul balls now. He has only two homers through 25 games this season. And that is what’s uncanny about this crowd. In any other year, whether or not there was enthusiasm about the Jays, there were always people cheering for or against Bautista. There were always a handful of Jays fans trying to will him to make something magical happen, celebrating meaningless home runs, yelling at harmless fly balls, trying to get a Jose chant going in extra innings on the road. Not so now.

***

Perhaps confident after having seen six of his pitches, perhaps taking a chance with two outs and nobody on, Bautista takes a huge swing at the first pitch he sees from Lester in the third inning. He is nowhere close to hitting it. He stumbles backwards out of the box, to little reaction. A man with his head resting on his hand doesn’t react to the pitch whatsoever.

He takes another huge swing at a pitch in the dirt for strike three. The inning is over. The crowd at Citi Field hardly seems disappointed. They are all looking, but the faces seem almost uniformly impassive.

***

I didn’t ask, because I didn’t want to derail a legitimate medical appointment that I actually needed, but I wanted to ask the doctor who the “everyone” was who said Jose Bautista was a big mean jerk whom the Jays were better off without. As fans, they probably didn’t have much different information than I did. I wanted to know where the “mean” thing came from—who had Bautista been mean to? Was this because of the bat flip, or the fight with Rougned Odor, which was also because of the bat flip? Maybe it was the arguing with the umpires, or the somehow still-present curl of the lip, the sneer of confidence. The fact that he said he’d been giving the Jays a hometown discount. Or something I didn’t know about—something only true fans would know.

I want to know if they still feel so strongly now that he is no. 11, not no. 19, and now that he is the Mets’ third baseman, not the Jays’ right fielder. If, as he lined out unceremoniously for the second out of the eighth inning on Sunday afternoon, they still jeered. After all, if he was a villain even after his terrible 2017 season, it would stand to reason that he still would be now.

And he is, really, still so much the same: slower feet, and a slower bat, but obviously the same player, with the same long-held mannerisms, down to his routine waiting in the on-deck circle. It seems strange that, given a simple change of context, someone who was such a big mean jerk—so much so that even non-baseball fans knew of his reputation—barely registers to the fans of the team he now plays for. It strikes me as strange, profoundly strange, that deep-rooted villainy could be so mutable in the same person. That everyone cared and, just like that, they didn’t. It’s only been six months. It’s only been three years since 2015.

Bautista finished the day 0-for-2, and the Mets lost 2-0. I don’t know when I’ll watch them again.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now