Over in the world of hockey, the unthinkable has occurred: The Vegas Golden Knights are in the Stanley Cup Final in their first year of existence as an expansion team. This is interesting for the obvious reason: Holy crap, what are the odds?! And for some less sensational reasons: How did this historically insurmountable disadvantage get flipped on its head?

That underlying bit of intrigue cuts right to the heart of our own game’s obsession with turning incompetence or irrelevance (or nonexistence) into a burst of gleaming, ring-winning dominance. Given what we know of the Rays’ and A’s economically driven aversions to bottoming out, it may even be that the Golden Knights’ triumph could inspire a future expansion owner to quietly envision a similar path in baseball, hoping to set the franchise’s course on a better trajectory by starting out with an amplified boom of enthusiasm.

MLB commissioner Rob Manfred has hinted at a desire to field 32 teams, though we’re not nearly close enough to say how the process would work. We simply have a reference point in the rules from 1997, and a provocation from the universe. So we ask: How would an expansion baseball team be built if its first-year goal was the World Series?

There are some prerequisite questions to answer. Such as …

What types of players would be available?

When the Rays and Diamondbacks entered the league in 1997, existing teams could protect 15 players in their organizations. They were required to use spots on players with no-trade clauses, while young players who had neither debuted in the majors, nor spent more than three or four years in the minors (depending on the age at which they were signed) were exempt from the whole process, as were players in the final year of their contracts.

Long story short, if expansion happened right now, some top prospects (Eloy Jimenez and Michael Kopech, for example) would require shielding. A great many (like Sixto Sanchez and Keston Hiura) would not.

The two expansion teams, per the 1997 model, would select 15 players each in a first round, one from each club. Then each existing club would get to protect three more players, and a similar second round would occur. Then three additional protections. Then a shortened round in which the expansion teams add seven more players. The new franchises wind up with 35 players.

At least in the NHL, the rules—when combined with salary cap situations—made a huge difference. Vegas’ draft came with fewer protection slots than previous iterations, and the unknowns seemed to intimidate existing clubs. The resulting crunch didn’t just make a higher quality of player available. Some teams were willing to pay Vegas to raid their cupboards in a certain way.

Rules will matter in baseball, as well. International spending is no longer a free-for-all. It is, in fact, restricted to the point where it’s difficult to see how anyone gains an advantage. Towering even over that: If front offices continue to treat the Competitive Balance Tax as a convincing salary cap imitation, some version of the dynamic seen in hockey could well be present in baseball’s hypothetical expansion.

What recent strategies would influence the expansion club’s thinking?

There’s a prevailing idea that the demolition of a major-league roster is the most likely way to reach that highest of peaks. The best talent is acquired in its infancy, the logic goes, and you’re best off stocking up. That’s what the Astros and Cubs did on purpose. It’s what the Rays and Nationals did before them in, uh, less purposeful ways. Then there’s the fire-sale approach most recently undertaken by the White Sox and Padres, who flooded their farm systems by lopping off and selling the shiny parts of badly misshapen rosters.

An expansion franchise could theoretically work with this model. Unabashedly seek the best available prospect talent, perhaps take on bad contracts that come with prospect compensation, bask in some automatic New Team Glow, and hope it all pops within a couple years. Or, or … they could do that but then flip talent for win-now players. That might, unfortunately, show their hand and tip the odds against them in a sort of early A.J. Preller way.

We have also seen teams—including those that chose to bottom out—accelerate or supplement their charge with prescient project acquisitions. Where winners in the 1990s and 2000s operated with variations on the mantra “get the best players,” the championship teams of the present and near-ish future will likely be constructed with a different mission in mind, something like “get guys you can mold into the best players.”

That’s not a new thought. There will be a book about it this time next year. It is almost as responsible for the Astros’ present dominance as the losing, it’s one of many reasons the Yankees remain a powerhouse, and it could be the vital factor in the resurgence of the Brewers. It’s not as clean to explain to someone as “tanking,” but it might be more relevant to the future of putting a baseball team together.

***

So how do you build an immediate winner? Well, sadly, you probably don’t start by nakedly proclaiming that intention to the world.

This quote is from August. I’ve thought about it pretty much every day the Golden Knights win. pic.twitter.com/meceYST9yR

— Emily Kaplan (@emilymkaplan) May 20, 2018

In a word, openness is the move. There would be a temptation to craft a master plan, to assume that one type of player will be available, or one inefficiency will be exploitable. And that’s probably a trap.

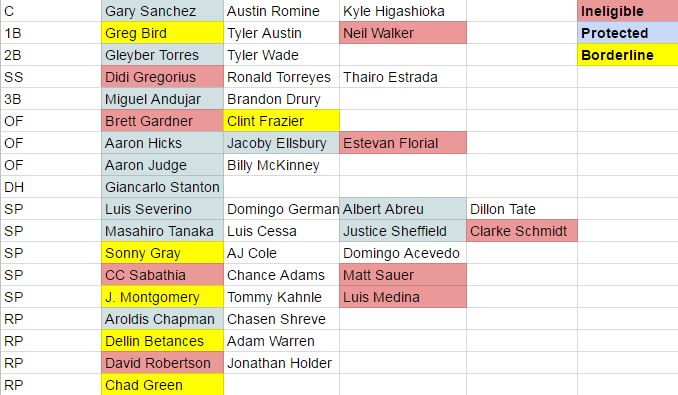

Let’s look at how the Yankees—one of the most loaded rosters—would shape up if an expansion draft materialized this winter. In the chart below, I’ve filled in 12 obvious and required protection slots (Jacoby Ellsbury has a no-trade clause and must be protected). There are also six players in yellow who would be up for three remaining protection slots. Assuming one is chosen, the remaining two would likely be shielded before the second round.

Uh, do you know which three they would protect? There are approximately 500 articles from the past month lambasting various hockey teams for the players they left vulnerable, the ones who became stars for the Golden Knights. With one exception (the Florida Panthers’ willingness to give up a proven scorer on a bargain contract was widely criticized at the time), most of the decisions that went bust came with valid reasoning in the moment. Some of the surprise team’s stars had posted good seasons before experiencing decline or becoming expensive blockages at their position. Others, like a 25-year-old named William Karlsson, came plum out of nowhere.

Everyone is going to have issues and problems to solve, and a blank slate affords this expansion team to “help out” in nearly every situation that could prove beneficial. These lessons from hockey could be taken literally, but they are best left tinged with some imagination. I’m going to try to distill them into a couple of bullet points.

Cast a wide net for decision-makers, so that the net for players can be more informed.

Despite rampant video and data scouting improvements, it still seems safe to assume a member of the Cardinals’ front office would have greater insight into Michael Wacha’s potential, or that a Yankees evaluator might know more about Greg Bird’s injury history.

More detailed knowledge could tilt the tables just slightly toward the expansion team. Aiming for an immediate postseason run means finding undervalued players you could get for a song. It means snapping someone up who could be overvalued by a different front office willing to deal. Lastly, it means trying to spot Charlie Morton-style diamonds in the rough. The more information, the better.

Look for players lacking in opportunity.

In addition to that information gap, there are a bunch of other gaps to consider. Gaps of immediacy, gaps of coaching philosophy, gaps of role and playing time. We know what the philosophy gaps can look like. Gerrit Cole’s move to the Astros. Jake Arrieta’s move to the Cubs. And they don’t have to be that seismic. It could be Bud Norris becoming a good reliever by ramping up his cutter with the Angels last season.

We also know that sometimes guys aren’t missing a third pitch or an eye for sliders as much as they’re lacking playing time. Accounts of the Golden Knights’ expansion draft judo reminded me, oddly, of the Tyler Thornburg trade. You may know it now as the Travis Shaw trade. Desperate for bullpen help, the Red Sox dealt away a supposedly marginal third baseman stuck behind the expensive Pablo Sandoval for a Brewers bullpen arm. Turns out, it was pretty much a charity giveaway that the Brewers happily received by virtue of understanding scarcity and being willing to get on the phone.

There is, of course, a swath of known star-level talent you simply won’t get as an expansion team. Then there are pieces in or around the Travis Shaw class that seem to pop loose every year without anyone noticing. Could you snap up older, uncertain talents like Mitch Haniger (.341/.428/.670 in Triple-A before a brief debut with Diamondbacks in 2016) or Justin Bour (.306/.372/.517 in Triple-A) before they establish themselves? Yes? Possibly? Yes.

Capitalize on lessened commitment.

Like the Golden Knights, this hypothetical expansion baseball team wouldn’t have anything on the books. That opens up all sorts of routes forward. Take on a big contract to see if a fading star has one last run. Take on a big contract to eat 75 percent of the money and trade the star. Take on a big contract to receive compensation in the form of a useful young player. You get the idea.

The lack of commitments provides other advantages, too. We saw the Phillies exercise one in outbidding everyone for free agent first baseman Carlos Santana this past offseason. There’s that obvious option.

Miles Mikolas is the latest player to arrive from Japan having figured something out, providing more evidence that dominance in Nippon Professional Baseball should not be taken lightly. Are there over-25 players who can be had from Japan using pure financial might?

There’s also the nonexistent playing time hierarchy. When everyone is stepping into a void, there is an opportunity to make “the way things are done” more effective from the jump. Get that guy with the crazy slider and try him in the bullpen (we’re going for one year, remember?). Attempt a fatigue-busting rotation at some positions without the awkwardness and weird pressure that comes with personal and financial history.

Lastly, it would be interesting to see how many players could be gathered with options remaining. Or, relatedly, could you compensate more of them to remain in the minors if they didn’t make the original roster in the spring? Avoiding the loss of talent in that time of uncertainty could prove to be a boon. Call it the J.D. Martinez Corollary.

***

All of these are small things, little (possibly prudent) bets here and there. Any team that’s going to do what the Golden Knights have done would need at least a couple of those little bets to hit the jackpot. With tighter restraints (yes, some self-imposed) on spending and a flatter distribution of knowledge, that feels increasingly true of any team. I don’t know if or when we’ll see expansion. I don’t know when we’ll see the next true teardown. I’m more convinced than ever, though, that there are plenty of novel ways out there to win big.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

We can't figure out the best possible team, since the protected lists were confidential. But, if you just take the players who were actually picked and put together a team with the highest 1998 BBR WAR, it's:

C Kelly Stinnett (1.6)

1B Aaron Ledesma (1.9)

2B Miguel Cairo (3.2)

3B Bob Smith (2.2)

SS Tony Batista (2.6)

OF Bobby Abreu (6.4)

OF Quinton McCracken (2.1)

OF Dmitri Yount (1.7)

Bench Joe Randa (1.8)

Bench Bubba Trammell (1.1)

Bench Damian Miller (0.6)

Bench Randy Winn (0.6)

Bench Andy Sheets (0.3)

Bench Jorge Fabregas (0.1)

SP Omar Daal (4.2)

SP Tony Saunders (3.1)

SP Brian Anderson (1.5)

SP Albie Lopez (1.5)

SP Esteban Yan (0.9)

RP Chuck McElroy (3)

RP Jim Mecir (1.9)

RP Hector Carrasco (1.5)

RP Jose Paniagua (0.9)

RP Brian Boehringer (0.4)

RP Rick Gorecki (0.2)

That looks like a playoff team. And one would have to assume that a team with perfect hindsight trying to maximize year 1 playoff chances would have done more than just pick the best year one performers, like draft prospects and trade them for better year 1 performers. So, there could be a baseball Golden Knights.