With another season in front of us it’s time to discuss baseball’s most penetrating current problem, which is of course the feral, mouth-breathing cats invading the diamond.

Oh sure, it’s a moment that’s always good for a larf between broadcasters as we admire in slow motion the physics of the feline form. But under that matted fur is a swarm of disease and trickery that you will never convince to love you. It doesn’t matter if I, I mean, a grounds crew member, has a perfect track record of pet care; convincing one of these wild ballpark cats to come home and be domesticated is a fruitless task that ends in bite marks and infection.

This, naturally, does not apply to Tony La Russa, who as the manager of the A’s in 1990 managed to successfully cajole a stray into the Oakland dugout after it had a full-on meltdown while a Coliseum’s worth of fans howled at it. Somehow, in a moment that almost certainly shattered that animal’s mind, La Russa was able to make a deep, personal connection with it using what we can only assume was telepathy. So formative was the experience that La Russa went on to found a no-kill shelter in the East Bay while the cat went on to ask the arresting officers at his DUI if they “knew who he was.”

But those of us without the ability to soothe panicked creatures by tapping into their tiny brains need physical barriers between us and their bodies that are made up of about 40% knives.

In any case, it vexes and infuriates me how no grounds crew has ever had a pair of thick work gloves on hand to protect them from the evil mouths, malformed teeth, and yellowed claws of the cats that invade our outfields. This is a deeply preventable moment for any grounds crew, and yet we watch it happen time after time after time.

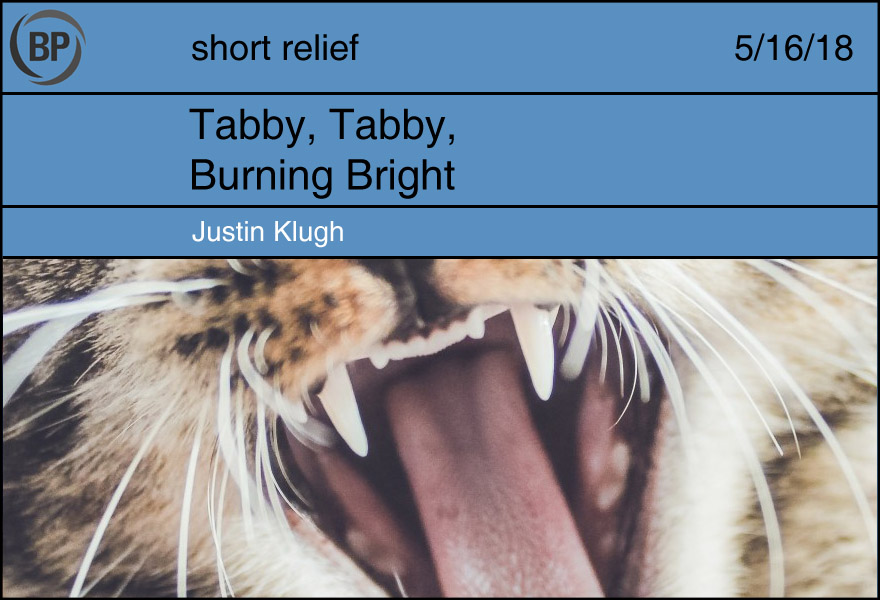

Does this look like an animal inviting you to touch it with your bare hands?

No. It looks like the midpoint of an ‘80s horror movie transition from “normal cat” to “house cat impregnated by slithering parasite blob that has been leaving toxic mucus trails all around the cul-de-sac which no one—not local misunderstood teen Brenda, who thought she heard something bumping into the patio furniture last night, nor gruff, divorced Sheriff Hughes who just wants a nice quiet summer for once—has been able to figure out the source of for the movie’s first half hour.”

Some cats just weren’t born to be touched. They were born inside of a rolled-up tarp, believing the universe in its entirety to be a long, hard cylinder that unravels every time it rains. For the good of your blood streams, grounds crew members, invest in a pair of hockey gloves to handle these animals. Or next time it could be your mucus trail we’re investigating outside the Millers’ house after they’ve mysteriously disappeared. Which is weird because, huh… their wood paneled station wagon is still in the driveway. Better call the sheriff. And what’s Brenda doing here?! It’s past curfew!

We are, as a species, hardwired for purposes of self preservation to be tribal. I think that wiring is a big part of why sports fandom works so well. Whether spoken or unspoken, cognisant or subconscious, we desire a way to feel connected to those around us. If you have ever been in a space with more than a few dozen people who all share a same desired goal, you know the appeal. There is power there, and safety. Our tribe. Our people. Our team.

I have identified with that conception, of “my tribe” for the entirety of my baseball life, until now. You see, I am a Mariners fan, and I’d maybe even go so far as to say I’ve until very recently I have been a Mariners obsessive. I have had season tickets, I have a not unembarrassing number of bobbleheads, shirts, funky giveaways, and framed moments adorning home’s walls, drawers and storage space. The day that the Mariners re-signed Ken Griffey Jr. in 2009 I gleefully left work and drove an hour and a half to Safeco Field to pay an extremely foolish amount of money on a jersey.

This background serves to mark today, where I find myself considering, if not leaving the only baseball home I’ve ever known, at least allowing myself considering my first real trip outside the village. “It’s not you” I’ll say, “it’s Ohtani.”

For Mariner fans, Shohei represents some combination of the forbidden fruit, and the holy of holies. He is to be neither viewed nor indulged, and if he must be either it should be done with the utmost contempt and disdain. He was, we tell ourselves, ours. He should be ours. Mariner fans self-identify as the fan equivalent of whatever plant it was that first grew back in WALL-E, but even we were not prepared to see the culmination of Jerry Dipoto’s years long plan go to our most hated rival.

And yet, there he is, striking out eleven in Minnesota, blasting home runs off Cy Young winners, running with the elegant grace of Eric Davis. Mariner fans are welcome to and understandable in their need to relentlessly boo him, as they did earlier this month on his first visit to Seattle as an Angel, but I cannot. Like Salieri in Amadeus, I would publicly will the Angels to lose a hundred twenty games but make arrangements to secretly watch each and every time Shohei Ohtani played, at worship as a faithful parishioner to his godlike abilities.

We have come along way since the days when our mere survival depended on us sharing life together. We are still tribal, and to a certain extent we will probably always be. But tribes draw lines, they are meant to keep certain things in, and other things out. For me, Shohei Ohtani represents the first time I’ve allowed myself to step outside the bounds of my baseball tribe. On glancing back, it looks rather small.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now