If you know only one thing about Astros right-hander Lance McCullers, it may well be that he set the baseball world ablaze by throwing 24 consecutive curveballs to stifle the Yankees in Game 7 of the ALCS. Or, more simply, that he’s one of them newfangled starting pitchers who throws his breaking stuff as much as his fastball.

Newfangled isn’t the same as young, though. The touchstones of this phenomenon have been middle-aged, at best: Established splitter wizards (Masahiro Tanaka, et al), old dogs trying new tricks (CC Sabathia, et al), and, uh, Rich Hill. All fascinating and important, they are nonetheless limiting as precedents for those they might inspire. This frontier is still relatively untrodden by starters in the formative years of their careers.

That’s where McCullers piqued my interest. He and Rays right-hander Chris Archer are the most prominent early-career hurlers to adopt this “upside-down” approach, but the young Astros starter has acknowledged the need for something more. He’s looking beyond the best-pitch-first insight at the heart of McCullersing or Archering or Corbining–intriguing paths that have not blasted true believers into the stratosphere on their own. And, if you’ll permit me to prognosticate wildly for a moment, I’d say his attempt to evolve from a breaking-ball-centric starting point could be widely relevant and hugely important in a matter of a few short years.

What, I wondered, is that next insight?

To get my bearings, I rephrased that broad question into this smaller one: Knowing the curveball is square one, how would McCullers and the Astros design the rest of his repertoire? I came up with an answer–a damned good one, I thought–before realizing it was all too easy.

***

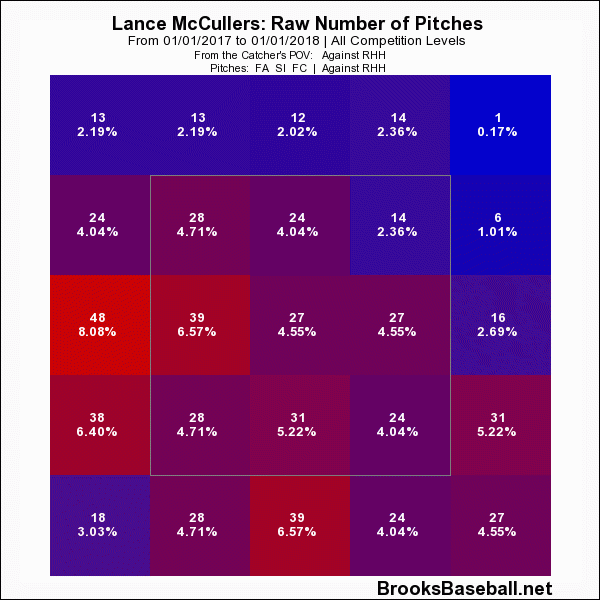

My original course of action was to study how his signature pitch sequences with other offerings. Lacking the rising fastball that many curveball specialists employ, McCullers has always fashioned himself as a worm-burner. His methods–namely, throwing everything low–can lead to some difficulties in the deception department.

Now, plenty of those curve-heavy pitchers use variations of shape and speed to keep hitters off balance–as opposed to the more common practice that our tunneling metrics gauge where every pitch is meant to look as similar as possible right up until the breaking point. Our numbers show that McCullers is not eschewing this form of deception. In fact, he uses it pretty well against left-handed hitters. He’s just got a platoon-split problem. A reverse one.

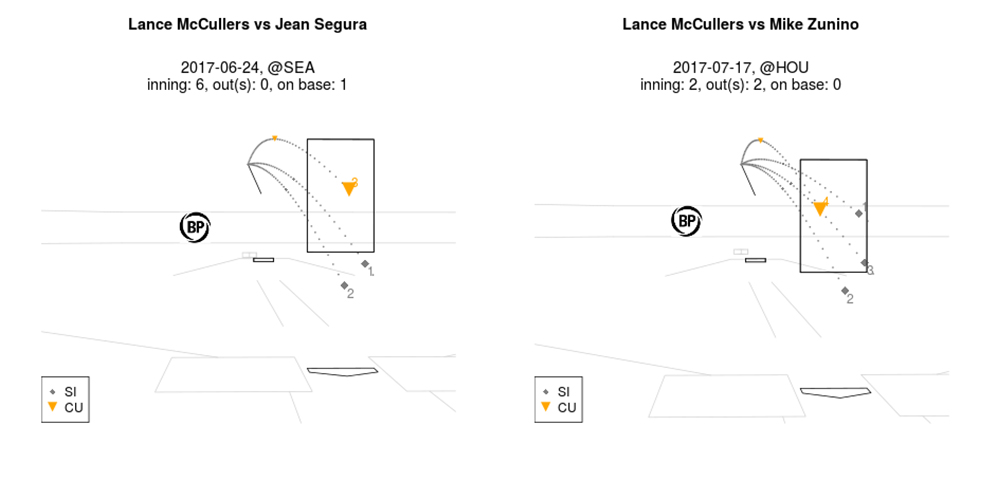

Righties see him more clearly, posting a .257/.344/.412 line over his career compared to .232/.305/.340 for lefties. Within his individual sequences, I spotted one major tightrope he’s trying to walk. The two-seamer and curve reveal their planes quickly. If McCullers throws a knee-high heater, the curveball will have to be in the dirt away to achieve deception. That particular sequence? He can do that.

What happens, though, when a hitter sits curve and easily lays off the low stuff? Often, they end up with his sort of visual.

If McCullers doesn’t give in, they work a walk. If he does give in, they get their shot to try and drive an elevated curve. My big eureka moment went something like this: Whoa, McCullers could just throw his two-seam high and outside to righties more often, above where he lives with the breaker. He never does that!

Maybe he could diversify his curveball’s shape a little–throwing a dropping version and a more slider-y version with different speeds. A beat later: That … sounds a lot like Corey Kluber?

Another beat later: That is Kluber.

***

It’s tempting to think of an unconventional pitch mix or approach as something conjured out of thin air, a burst of pure creativity. But creative leaps, in all sorts of fields, are more often born of constraints. Kluber’s four-seam fastball wasn’t great. Then he didn’t get the grounders you’d expect from a sinkerballer. Eventually, he played his nebulous but incredible breaking pitch off his cutter’s sped-up swerve and the fastball’s opposing horizontal movement, and voila.

McCullers, unfortunately, might not have glove-side command of his fastball. We’re going to watch a ho-hum sequence from last season to get a glimpse at that possible limitation. Before we start, look at where his catcher, Brian McCann, sets up.

It’s a 1-1 count, and he wants McCullers to get ahead by running his two-seam back over the outside part of the plate. No one chases his two-seam. No one chases Kluber’s, either. This particular offering’s power comes from how it can sneak into the zone after appearing to set a course well wide of the imaginary barrier.

Kluber has totally mastered this. As he peppers the high, outside corner, hitters swing at the rare up and in heat. His sweeping breaker appears there like a mirage in the desert–a mistake fastball, sent from the heavens just for them–and then vanishes.

If McCullers sets the bait as McCann asks, it could get the batter, C.J. Cron, to two strikes and put him on the defensive against anything in that vicinity–making a subsequent curve even more deadly.

The ball ends up more on the inside part of the plate, though, which doesn’t add anything new into Cron’s calculus. So when that two-strike curve breaks off–as pretty as it is–it doesn’t convince him to commit.

That might just be a limitation. What can McCullers do on the other side of the plate, where he often does locate the fastball (intentionally or not)? One sequence will do for showing the potential here. Against Aaron Judge in Game 4 of the ALCS, before he went all-curve-all-the-time, McCullers broke off this tandem.

High, inside two-seam with much better horizontal movement than usual:

Followed by a curve that appears to burst from his hand in a similar way, only to dive toward the plate:

Boom, strikeout.

This spring, McCullers amped up the movement on his two-seam, as helpfully documented by Rob Friedman’s essential @PitchingNinja Twitter account. It looks better to the naked eye, a notion confirmed by early movement numbers. Having thrown it 80 times so far in regular season action, it has averaged almost three inches more horizontal, arm-side movement than it did last season. He’s also throwing it for more strikes, but I’d be lying if I said the sample is meaningful for that last bit.

No, the renovated fastball provides McCullers the opportunity to change the circumstances under which he’s working. Yes, there’s a lot of evidence to suggest he may struggle to use this great-looking blitz-ball in the traditional way. It may not matter, though. While it was always naive of me to think he could follow a Kluber roadmap, he’s demonstrated he can blaze a trail all his own. Perhaps he will bust righties in on their hands with it and then see how his curve can play off it. Maybe he does find a way to use it as a chase pitch.

I truly don’t know where he will go with it. I don’t think anyone does. We like comps and patterns and role models. We like to understand what a guy should be doing, so we can watch and say whether he is doing it. Some people (raises hand) like it so much that we can fall into the super-duper-obvious trap of funneling someone on to one of these tracks when there simply isn’t a preexisting track for him.

I’m going to stop here and wait. These are the constraints with which McCullers appears to be working. He may soon reveal to us a totally novel way of getting around them. Let’s watch closely.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now