Yankees third baseman Brandon Drury left Saturday’s game against the Orioles complaining of vision problems and dizziness. It was later revealed that Drury, obtained from the Diamondbacks in the offseason to prepare the way for New York’s promising infield prospect duo of Gleyber Torres and Miguel Andujar, has been suffering from migraines and blurred vision for years, and had hidden or downplayed the problems to both Arizona and New York’s medical staffs. Finally, mired in a hitless streak, it had grown to be too much.

The New York Post, in their story of the outcome, described Drury’s actions as “coming clean,” and while some fans reacted with sympathy, particularly those who have ever gone through even one migraine headache, others were less charitable. Blame had to be distributed, and so it was: to the Yankees’ training staff, for failing to uncover this invisible malady (the Diamondbacks had run an MRI in 2016 and found nothing); Yankees general manager Brian Cashman, for making a trade that might result poorly; and, of course, on Drury himself for hiding his problems.

Cashman was quoted in the Post as saying:

All I care about is finding out what’s going on. He’s in a great city and we’ll give him the best medical care that New York City has to offer. I can’t say what my level of concern is at this point.

Though I personally love the last line, and am considering ending all my work e-mails accordingly, it’s the sort of sentiment we would hope for in all of our bosses. All of them except baseball, where performance reviews are both public and horribly quantifiable, and where the expectations of winning supercede, in some minds, any possible element of humanity.

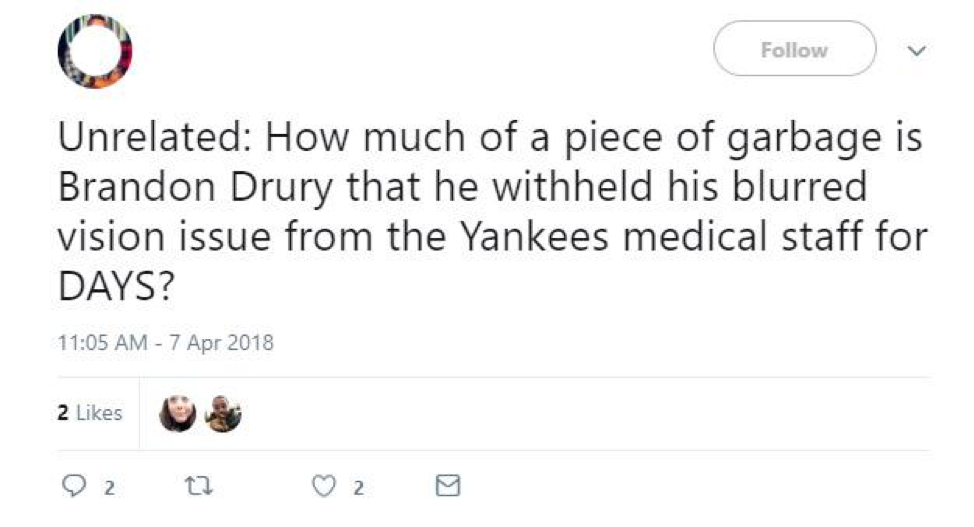

One anonymous tweet:

Yes, this is cherry-picking, but it’s hardly a unique sentiment. We see the same accusations, year after year, each time a player has the temerity to get injured, or participate in a holiday for religious reasons, or have a child. The money is always lobbed up as an excuse, but in the end it’s not the money that matters. It’s that Brandon Drury owes his future performance to his team’s fans, that he is beholden to them to win baseball games no matter what the personal cost.

Which is, in the end, part of the problem.

***

The most recent book by charming and irreverent popular science author Mary Roach is called Grunt. Roach likes to sift through the quiet, weird corners of modern science—her first book, Stiff, was about cadavers—and this one is not about the traditional focus, the blowing up of things, but rather the maintenance of an enormous, ponderous, highly-trained group of men and women. There are chapters devoted to their clothing, the way they protect themselves (and the way they are repaired when the protection fails), the prevention of disease. But perhaps the most resonant of all is the chapter on the military tradition least similar to everyday life: submariners.

Life in a submarine is simultaneously demanding and boring; it’s not an easy life, sharing a single metal tube with too many comrades, but most of the time the work demands readiness rather than action. Submarines are, after all, more preventative than active in peacetime. It is also, as Roach discovered, a very difficult place to sleep. Between the physical logistics of sleeping on hammocks and crammed into impossible corners, the lack of sunlight to guide the circadian rhythm, and the endless, vital drilling, most naval men and women receive ridiculously little sleep in a 24-hour day, generally in the four-hour range.

As any new parent will flatly inform you, lack of sleep is a big deal. It diminishes your mental acumen, your reaction time, your memory. It makes you pretty terrible at everything. (Cramming before the final, as I did far too many times in college, is a good way to worsen your final grade.) And it’s particularly bad for people who will then wake up from this brief slumber to … stare at screens. Folks in the navy admitted to Roach that it’s not uncommon to see a man asleep at his post.

So given how damaging such a situation is for the readiness of a nuclear submarine (also: we’re talking about a submarine with nuclear weapons), why is it allowed? Why doesn’t anyone do anything? Well, changing anything about military practice is a battle against the kudzu of red tape. But also, there’s a cultural issue in the subs themselves: depending on how charitable you feel, either machismo or simply a collective action problem. No one likes to be known as the one guy who likes to sleep too much.

***

This brings us back to Brandon Drury, who is not responsible for preventing or starting World War III, but works under similar clubhouse conditions. He is not alone; the sport has made some progress in evaluating and understanding non-traditional problems with players, but it has a long way to go. The general rule: whatever the problem, gut it out, lie if necessary, and let the coaches decide when you shouldn’t play. Sports are filled with the glory of men who played at 60 percent, as if injuries only caused pain and not limited performance, and that all pain could be ignored by the strong. Complaining is not an option. Phillies manager Gabe Kapler, in one of his many counter-cultural moves, eliminated the pre-existing practice of awarding a “sensitive bus” to anyone who failed to follow the code of silence.

It’s a workplace practice we would find unimaginable in any other setting, where employees were forbidden to communicate about their problems, and employers were assumed to offer zero flexibility. But there’s another element as well, because Drury not only had every reason to deceive his employers for the sake of the team, he also was bound to it for his own sake. Drury, at 25, is still under team control; 2019 will mark his first visit to arbitration. As we stumble into an era of free agency in which players are largely paid for what they promise to produce, rather than what they produced in the past, the economic system remains highly retrograde for the younger class. Particularly in arbitration, when untrained arbiters are provided a list of stats and asked to compare to others, Drury’s financial future is tied directly to getting out on that field, and hoping he can muddle through.

Cashman’s quote—we will do what it takes to make things right—is not only the morally preferable one, it’s also optimal for the long-term interests of both employee and employer. The trouble is that in our modern economic climate for baseball, the Yankees have little incentive to think in the long term. Andujar is, barring disaster, the heir apparent at third base, and Drury is doomed when healthy to become some other, second-division team’s starter. And because of the lopsided nature of how baseball players are paid, Drury is forced to take on all of the risk—and endure, it shouldn’t be forgotten, the constant blinding pain—that his medical issues entail.

Ultimately, it’s natural for baseball fans to react to bad news like this and search for someone to blame. But there’s no one at fault here; everyone is trying to win. What we need, when we have collective action problems like Drury’s and the radar man of the nearest submarine, is to create fair systems to mitigate those problems as much as we can. Instead of blaming Drury for lying, or expecting him to play hurt, we need to change the way the game is run to remove his incentives for doing so. And most of all, we need to be able to give him a break. We’re all better off at our jobs when we’re allowed to be human.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now