Between now and Opening Day, we’ll be previewing each team by eavesdropping on an extended conversation about them. For the full archive of each 2018 team preview, click here.

San Francisco Giants PECOTA Projections:

Record: 82-80

Runs Scored: 695

Runs Allowed: 681

AVG/OBP/SLG (TAv): .253/.318/.391 (.257)

Total WARP: 27.5 (8.9 pitching, 18.6 non-pitching)

Daniel Rathman: A lot of things have to go wrong for a team widely projected to contend for a Wild Card berth to finish a walk-off home run away from the worst record in baseball. A lot of things did go wrong for the 2017 Giants, prompting a lot of offseason changes, from the roster to the coaching staff to the front office. So as we look at the 2018 Giants, the overarching question is how many of the myriad factors that felled them last year will reverse themselves this year?

PECOTA is generously projecting an 18-game improvement, which would take them from 64-98 to 82-80, but still leave San Francisco a few games shy of a playoff spot. How do you feel about that?

David Brown: One thing about the Giants that seemed to be true, when they were good in 2010, 2012 and 2014, was that the whole turned out to be greater than the sum of the parts. Whether that’s something about how Bruce Bochy manages them (although his style hasn’t always jibed with what analytics would do), I don’t know. But I, too, am feeling an optimism for the Giants in 2018. Is it Bochy? Unrealistic expectations based on past results? The acquisitions the team has made? Putting Brian Sabean back in charge of player personnel and knocking back Bobby Evans? It just seemed like they had one of those seasons in 2017 where everything went wrong and, for as lucky as they were in some ways in ‘10, ‘12, and ‘14, the Giants were just too unlucky in ‘17.

As for PECOTA, you could say that 82 victories for the Giants might be conservative. Just a year ago, when the Giants were coming off an 87-win season in 2016, PECOTA pegged them to go 88-74. Few, if any, saw San Francisco’s collapse to 64-98 coming. I feel like 85-86 wins is closer to where projections should be, and if the Giants have a lot of things go right, 90 wins is possible. Am I drinking the Kool-Aid? Maybe. But Kool-Aid can be good!

Rathman: There’s no question that 2017 was an everything-went-wrong type of season, but it’s worth noting that the Giants also stumbled into the playoffs in 2016, going 30-42 after the All-Star break. There were cracks in the armor going into last year, cracks that suggest the 88-win projection was overly bullish. On the other hand, some of what went wrong was certainly flukish. Brandon Crawford’s series of personal tragedies. Madison Bumgarner’s dirt-bike accident. Brandon Belt’s latest unfortunate concussion. Perhaps the Giants’ luck will even out.

The other source of optimism is the rebounds some of their returning players enjoyed down the stretch. Crawford hit .283/.348/.441 in the second half. Hunter Pence batted .291/.360/.467 after his legs healed up in late July. Bumgarner seemed to recover fully from what could easily have been a career-ending wreck. As bad as last year was, the Giants shouldn’t be any worse for their 2017 wear when they take the field on Opening Day. And while many of their rivals have stood pat this winter, they’ve brought in some reinforcements.

Brown: Let’s look at some of the new guys. Andrew McCutchen, from his rookie season in 2009 through 2015, was one of the top players in the league. Only three hitters over that span with at least 4,000 plate appearances produced better wRC+. Injuries led to a big drop-off in 2016, but he was a beast again for most of 2017. Sure, he’s 31 and most of his best years are behind him, but for this season, heading into a free-agent offseason, there aren’t many other players I’d rather have. He’s a huge add.

Evan Longoria no doubt dropped off in 2017, after flattening out in 2014-2015 as well. He was great in 2016, though, and if he reverts to career averages again in 2018, the Giants will have one of the better third basemen in the league. He’s been top notch defensively, too. Cutch and Longo are ifs, but they’re not huge ifs.

Assuming, just generally, that some of the other Giants who had off seasons in 2017 return somewhat to form—notably Belt, Pence, Johnny Cueto, and Mark Melancon—McCutchen and Longoria are huge, huge catalysts to big-time improvement. What do you say, Daniel? Are you with me? Let’s jump head-first into McCovey Cove, c’mon!

Rathman: The age that we consider “old” for baseball players certainly seems to be inching downward. A few years ago, we were wary of teams investing in 36-year-olds—for good reason. Then, it was 34. Now, a lot of us are worried about what Longoria, who just turned 32 in October, and McCutchen, who turned 31 three days later, have left in the tank. The Giants don’t need and didn’t pay for peak Longoria or prime McCutchen. I think you’re right to point out that while there are question marks attached to both, each also brings a lot to the table, and assuming the Giants’ returning stars bounce back, they would simply be asked to complement an already productive core.

Brown: Uh, oh, tangent alert. You bring up a point here about aging that strikes me funny. Elephant in the room, if you will. (Wait—wrong side of the Bay.) Are these fears about players declining in their early 30s because we’re afraid of a waning influence of career-extending PEDs due to drug testing? That could be a thing, right? Aside from the drugs, it strikes me that (in part because of the money available) players in their early 30s still must be in better shape than at any point in the past. And it’s because of legit weight training, better diets, legal supplements, better overall playing conditions, and travel factors.

There’s also this separate fear out there about how players of this and coming generations won’t want to stay in the game and coach since they don’t need to because they don’t need the income. At the same time, the players still playing the game should be able to keep doing it at a high level for longer. It would require more research obviously, but are players really declining earlier, and if so, why? Hey, I guess we should get back to the Giants specifically, but I thought you raised a fun point there.

Rathman: The Giants also have a few peripheral players who might be on the cusp of becoming significant contributors. I want to highlight two, in particular, who could turn the corner just by better deploying measurable skills they already have.

On the pitching side, Chris Stratton is a candidate to break out, and the front office’s diversion of resources to the lineup and bullpen might indicate internal confidence in their 2012 first-round pick. Stratton was essentially a league-average pitcher (101 cFIP) in 58 2/3 innings last year, but he flashed the potential for a good deal more. The 27-year-old’s weak link is a mediocre fastball, down a few ticks from his collegiate days, yet he threw the heater 62 percent of the time last year. His best pitch is a curveball that led all major leaguers in spin rate.

At 3,105 RPMs, Stratton’s hook far outpaced those of curve-loving pitchers like Rich Hill (2,798) and Charlie Morton (2,875). Spin rate isn’t the only determinant of an offering’s effectiveness, but opponents booked only one extra-base hit on Stratton’s bender in the 206 times he spun it, and it was the kill pitch on 23 of his 51 strikeouts. Seems safe to say that he’ll be more effective if he finds a way to utilize the breaking ball on more than 16 percent of his deliveries, and he was already on his way to being a viable back-end starter.

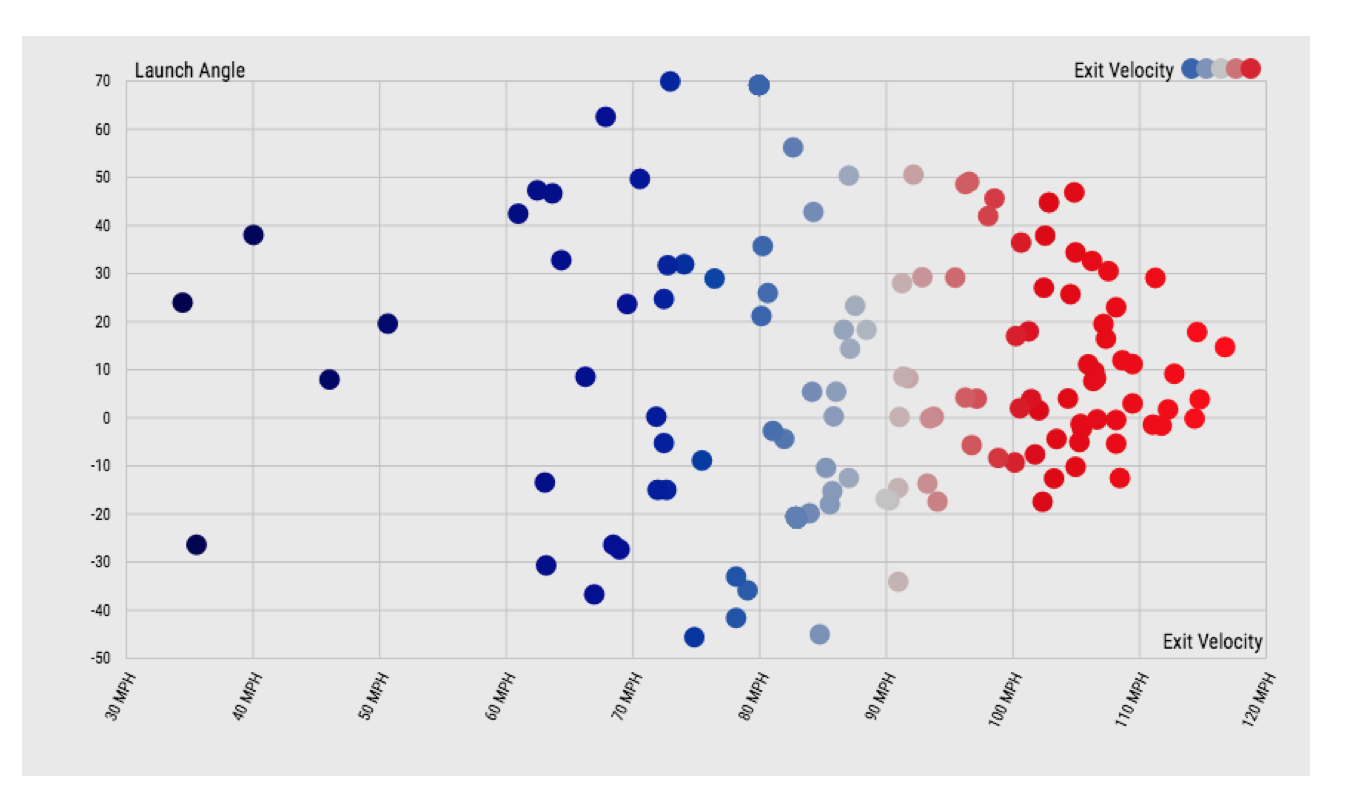

On the hitting side, Mac Williamson was buried by the offseason additions of the right-handed-batting McCutchen and Austin Jackson, but he might force his way into a big-league role. Williamson worked over the offseason with Doug Latta, a private hitting instructor best known for helping to transform Justin Turner from utility man to star. What was Williamson after?

At 6-foot-4, 240 pounds, the former Wake Forest star can put a 110 mph charge into the ball, but that doesn’t do you much good if your hardest hits are on the ground. All those bright red dots in the above chart were what you might call “wasted barrels”—balls that Williamson squared up but pounded into the dirt because of a sub-optimal swing plane. Enter Latta:

Mac Williamson 2b! pic.twitter.com/zS3km8Udnv

— Craig Hyatt (@HyattCraig) March 4, 2018

No two players are exactly alike, but Williamson came to Scottsdale with a retooled swing that clearly evokes Turner’s. The controlled leg-kick gather, the low hand-set, the intent to stay behind and work up through the ball—all of it looks like a sound plan to help Williamson elevate and celebrate more often. He’s been doing plenty of that in the Cactus League and would be at least a quality bat off the bench if he can maintain those gains when the games begin to count.

Brown: The Giants having Stratton turn into an effective starter for 30 games would be huge, perhaps the one single biggest key we’ve mentioned so far. It struck me as funny that when the Giants went and added Longoria and McCutchen, they didn’t keep going and add, like, Lorenzo Cain to play center field. They also didn’t add another starting pitcher, either, and it seems like relying on Stratton and Ty Blach for the rotation is kind of a stretch. The front office (obviously?) didn’t want to bring in any free agents tied to draft-pick compensation. Fair enough, that thought process seems to be going around the majors.

The Giants also have some decent minor-league depth we should expect them to call on; Tyler Beede and Andrew Suarez should be ready to promote soon. I just feel like they could be short here, especially if, say, Cueto or another of the Big Three starters encounter any trouble. Not a lot of margin for injury or error.

Rathman: And the thing about having question marks at the rear of the rotation is that, even though there are three potential workhorses up front, it means lots of innings for the bullpen. So, let’s talk about that.

Brown: The Giants do have a couple of backup plans on the roster in case Mark Melancon doesn’t return to form (immediately or at all) as closer. The problem there is, setup men Sam Dyson and Tony Watson are both coming off somewhat troubling 2017 seasons. These relief pitchers, they tend to flip it on and off without notice. There’s a chance Dyson and Watson could be mediocre at best, so will the Giants even be able to get to Melancon? And will he be healthy regardless? Melancon had been one of the steadier relievers in the league—until 2017—and he’s also trying to come back from surgery on his right forearm in September. Melancon is 32 as well (the dreaded early 30s!), so once you start talking about guys who get cut by a surgeon and they’re over 30, it doesn’t help their chances of bouncing back. I don’t know, the more you talk about the Giants, the more warts you see, the more pitfalls appear. They might need a lot of luck to get to 85 or 86 wins.

Rathman: While Watson may no longer be the dominant late-inning man he was earlier in his career, he can’t possibly be wobblier than Steven Okert and Josh Osich were, so the Giants should see some degree of improvement in their left-handed relief corps. Will Smith is sort of the forgotten man in this bullpen, but both his return timetable—early May?—and immediate effectiveness are wait-and-see propositions. If he comes back strong, that could be an impactful duo. Derek Holland has opened some eyes in camp as a non-roster invitee; if he makes the team, either he or Blach could figure into the bullpen mix, with the other rounding out the starting five.

On the right side, beyond Melancon and Dyson, keep an eye on Hunter Strickland. His control regressed in 2017, and he was extremely vulnerable against left-handed batters last year, but the 29-year-old has looked awfully good this spring after refining his slider with the help of John Smoltz. If Strickland has a reliable breaker to get hitters off his mid-90s fastball, he could emerge as the righty setup man the Giants need.

Brown: Last but not least, we should talk a little Buster Posey. Two years straight, he leads SABR’s defensive index among National League catchers, plus he wins his first Gold Glove in 2016. But in 2017, he hits 30 years old and we see a bit of a drop-off. His framing numbers in 2017 were a tad above neutral. Now, I still get a little uneasy talking about defensive ratings, because I’m not quite sure of how accurate they are. But he’s turning 31, and the Giants can’t really afford another huge drop-off from their best player. (His hitting bounced back in 2017, by the way, after being merely “good, especially for a catcher” in 2016.)

He’s had a bit of an ankle tweak in spring training, but is otherwise healthy. He’s just … aging, like the rest of humanity. How much longer can he be Buster Posey, as we know him?

Rathman: I’m not sure if we have enough years of framing data to truly map out an aging curve for that skill, but that’s the one defensive area in which Posey most obviously regressed last year. We may need another year before we can conclusively say that his value in the squat has dipped.

Offensively, Posey seems to be trading off some of his raw power to sustain his outstanding contact rates. He’s begun toying with no-strides, toe-taps, and other load-stride mechanisms besides his customary leg-kick, all presumably in an effort to maintain his balance at the plate. I think he has a few more years of being at least a good-for-a-catcher hitter, which probably means he has at least a few more years of catching. By the end of his contract—he’ll be 34 on Opening Day, 2021, the final year of his existing deal—the Giants may face a slew of tough decisions concerning the face of the franchise, assuming the National League has not yet adopted the DH.

Brown: Hey, one season at a time, man.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now