The acknowledgement of the relationship between Aristotle and baseball first occurred in the 1912 Broadway play “Elevating a Husband,” wherein one character asks another, “what do you know of Aristotle?” Surmising this to be a test of his baseball knowledge, the second character responds in kind, “who was the first fellow to lay down a bunt?”

Whether due specifically to this play or following the general trend of the times, baseball writers latched onto the relationship, dubbing a succession of men over the decades “the Aristotle of baseball.” The esteemed title was first granted to Connie Mack in 1913 after he managed the Philadelphia Athletics to a World Series victory. The title then passed in 1924 to William G. Bramham, then-president of the South Atlantic League, the Piedmont League, and the Virginia League, in addition to being a high-ranking member of the Republican party. Following him was Leo Durocher, who received the honor in the early 1940s, after leading the Brooklyn Dodgers to the team’s first winning season in seven years. Finally, the title rested with the radical Branch Rickey in the 1960s.

Among the careers of these four men weaved those of the only two Americans named “Aristotle” to play professional baseball. The first, Aristotle Lazarou, pitched two years of minor league ball in 1943 and 1946, and the second, Aristotle “Harry” Agganis, played one season for the Red Sox before dying of a pulmonary embolism in 1955 at the age of 26. Though these two were, in the literal sense, the Aristotles of baseball, they joined a community of others who never quite achieved the title.

Intent on matching the philosopher’s distinction between the particular and the universal, after the death of the physical baseball Aristotles, the relationship between the philosopher and the game assumed a more metaphorical form. Writers like Don Whitehead comforted distraught fans by evoking the philosopher’s notion of tragic catharsis, outlined in the Poetics and drawn from his observing theatre goers. In 1992, Aristotle’s Politics was re-written as a shorter treatise titled “On Baseball.”

Even for a country which had largely ceased teaching the classics, the philosophic nature of baseball was impossible to ignore, and the thinker who focused on community and friendship became the link between the Ancient and contemporary worlds. As the conversation on the relationship between Aristotle and baseball expanded, it left behind the simplistic and imprecise terms under which it entered the sport in 1913, instead centering the question posed in 1971 by frustrated manager Charlie Fox, “What do you want me to be, an Aristotle?”

“You know how Einstein got bad grades as a kid? Well, mine are even worse!” — Calvin and Hobbes

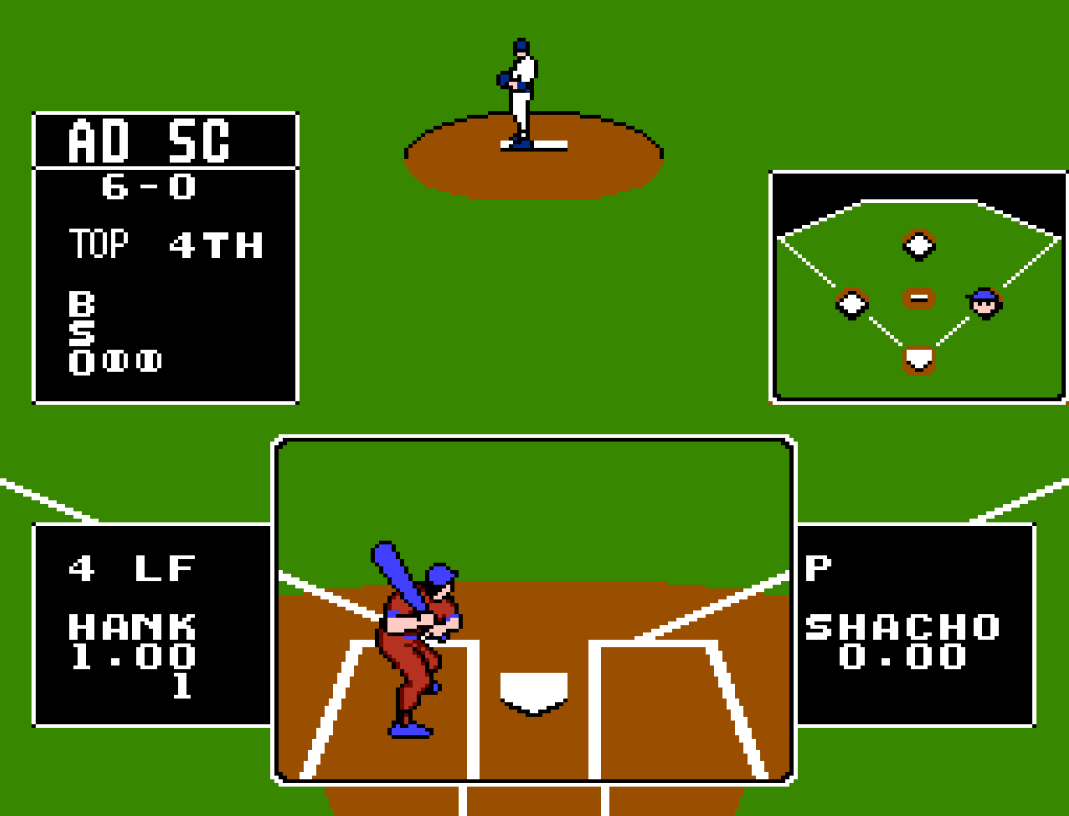

Baseball Stars was a simpler, more progressive time in sports. There were only eight teams and no replay, unless you had an emulator. Many of the teams were top notch, including an all women’s team. The notable exception of the last-place SNK Crushers, who just didn’t try. They traded away basically anyone of worth, not getting much in return except for some hangers-on and mostly-in-shape baseball connoisseurs who had no professional experience but did bring their own baseball bats. They kept getting worse. They kept losing. They had Shacho.

Meanwhile, the team you made (yes, you were there in this story, I didn’t need to tell you that) started poorly and had trouble beating the Crushers. But once you got the hang of stealing second with a man on third and let the starting pitcher tire himself out by the fifth inning, you started poking some singles through the infield and posted some crooked numbers. The money started pouring in and your players trained to get better. The SNK Crushers were once again the worst team — a perpetual benchmark challenge for the next create-a-team to pass by. Eventually the American League Central asked them to leave.

The logic that SNK’s general manager used had a fatal flaw of assuming a draft existed after the league. And maybe it did, but the whole point was to improve in season. The only way to get better was to win games and sign more free agents. Besides, if you need more proof: fire up Baseball Stars today. SNK hasn’t figured out how to improve its team in almost thirty years.

cc: Major League Baseball general managers

On three separate occasions you have attempted to engage Mr. Bruce Sutter. The reason is not important now. Perhaps you are complimenting his beard on its courage. Perhaps you are insisting that he is not a human deterioration of the standards of the Hall of Fame. Perhaps you are hinting that the powder blue of his uniform is not only timeless, but that it brings out his colorless, vacant eyes.

None of this matters, because Bruce Sutter’s murmur of assent, voiced half a beat too quickly to allow for comprehension, has betrayed his disinclination. He is looking up and to the right, not the cliched calculating flick of the eyes so common to the television sociopath. Instead he is looking beyond you at a bird, or perhaps even beyond the bird, beyond the sky and the space behind that, to a place that cannot exist and, therefore, neither can you.

Bruce Sutter is too polite to tell you this, too cordial to inform you that he would happily murder you without moving a stooped shoulder, excise you from his life and never allow the idea of you to revisit him. I just want to be a baseball card, he thinks to himself as you prattle on about his role in the rise of the save statistic. I want to be a face tacked to the numbers that represent my life’s work, encoded to the point of incomprehensibility. Bruce Sutter feels no ill will toward you; it is hardly your fault. You are simply a bird placed in front of a marble statue. You cannot understand what it is to be Bruce Sutter, not the greatness but also not the smallness, the weariness. It’s no one’s fault that no one can understand each other, or that they feel equally compelled to hope to. But some men must wear powder blue, and thus answer for it.

“I’m just trying to take it one game at a time,” he whispers, not really answering your question, if indeed you asked one.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now