Jazz is probably the music best matched to baseball, for obvious reasons: both American inventions; both solo players collaborating on a team effort, finding variations and improvisations within rigorous structures, and so on. But who is baseball’s suited composer?

It might be Charles Ives (1874-1954), who recognized early that his dissonant, dissident music would never make him a living—it was largely unknown in his lifetime—and went into the insurance business, in which he was remarkably successful (his innovations helped lay the foundation for modern estate planning). He composed in his spare time. His life and in some ways his work closely resemble, eerily so, that of another great American artist, the poet Wallace Stevens, who was Ives’s contemporary.

Ives was a good athlete. The track coach at Yale, where Ives went to college, lamented the kid’s commitment to music, for in his estimation Ives could have been a world-class sprinter. Ives played baseball throughout his youth—he captained his team at the Hopkins School—and called one of his earliest compositions, Variations on “America,” a notoriously challenging organ piece written at age 17, “as much fun as playing baseball.” (It would make deliriously captivating ballpark music.) Asked later in life, regarding his music, what he played, he replied: “Shortstop!”

Among Ives’s works are baseball-themed piano studies. These inspired an entire book, Timothy A. Johnson’s Baseball and the Music of Charles Ives: A Proving Ground. In it are engaging discussions biographical, musicological and historical. (Is Rube Trying to Walk 2 or 3!! about Rube Marquard, Rube Foster, or Rube Waddell? What exactly does the title mean?) Ives departed from baseball as a compositional subject early in his career, but the game’s own compositional logic-of-opposites—scrupulousness and nerve, beauty and disharmony, tradition and originality—remained hallmarks of his extraordinary work.

Along with his radical art, Ives had radical politics derived from staunch populist instincts. He once submitted an Amendment to the US Constitution that would have allowed citizens to submit proposals for legislation. His steeping in baseball is a salutary and timely reminder that the national pastime, too, is fundamentally radical (and populist). It is the insoluble game that refuses to cooperate or capitulate.

Here is Ives’s Some South-Paw Pitching! (“to toughen up the paw,” Ives notes beneath the title), which you can listen to in less than the average amount of time it takes for one ball hit into play to be followed by the next. The busy left hand crosses the right, rather like a lefty throwing a pitch. After its 150-odd seconds of Ives’s wonted antic pandiatonicism and neological directions (“Allegro molto, spirito, agiganto, hitopo, conswato!”), the study’s last bar gives this final instruction to the pianist (or pitcher?): “after a 2nd thought look for a boy in the 2nd row!” Then the piece concludes in its own jarring way, after Ives’s tirelessly contrarian fashion: with a familiar Amen Cadence, freezing the hitter with a soft F-major chord right down the middle.

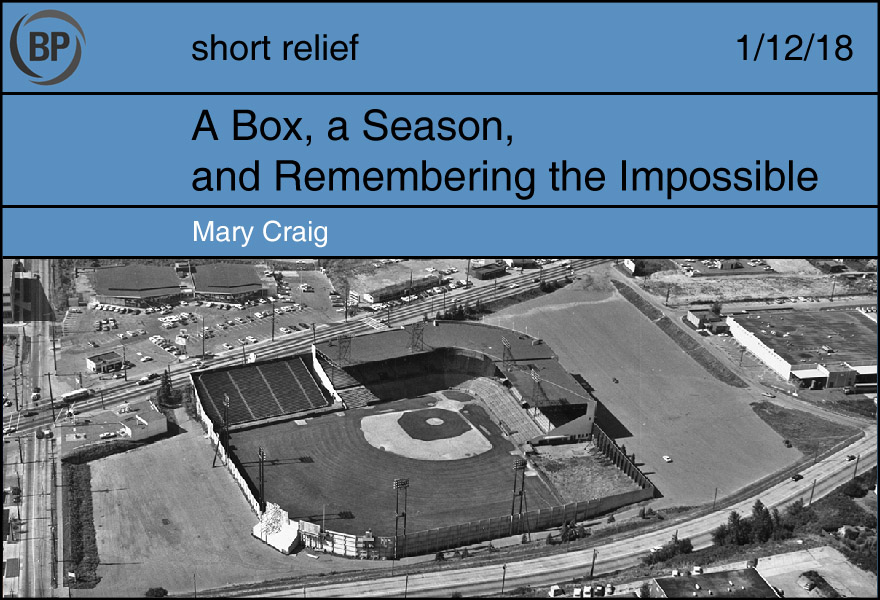

One of the allures of baseball is that it makes the seemingly impossible possible. It should not be possible to throw a sphere of rubber and string 100 mph, but it is. It should also not be possible to hit that same sphere 500 feet, but it is. Though baseball has largely withheld its original structure, it is constantly redefining the impossible, melding together the allure of the present with reverence for the past.

The 1954 Seattle Rainiers finished the Pacific Coast League season in fifth place, prompting general manager Dewey Soriano to turn to his old friend, Fred Hutchinson, for assistance. The former Rainier, who saved the team as a 19-year-old in 1938, quickly dismantled the roster, instead acquiring an assortment of former major leaguers, from Vern Stephens to Ewell Blackwell, with whom he hoped to regain his own professional career.

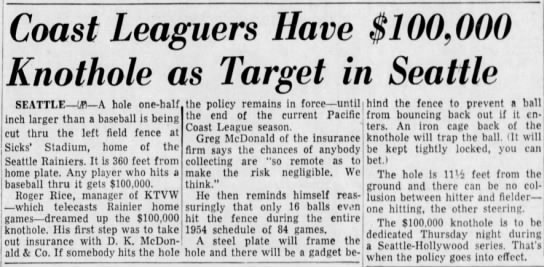

Beginning with the season opener on April 19th, the team amassed wins and former major leaguers at an astounding rate, and fans came flocking back to the team, often overwhelming the little stadium. Roughly one month into the season, KTVW TV station owner, Roger Rice, added a new take on the impossible when he installed a small hole attached to a box on left field wall, one inch larger than a baseball, and offered $100,000 to the player who could hit a ball into it.

The team contained no superstars; no player hit over .300 or accumulated more than 13 home runs, and the team as a whole lacked power. But they did love hitting doubles to left field. And fans loved watching them do it, each hoping to personally witness the spectacle of a ball passing through that tiny hole.

Of course, there is a limit to what is possible, and so no player accomplished the feat or came close to doing so. The box was quietly removed at the end of the season, and the contest was never again implemented or discussed. Over the course of 84 home games, it shrunk to the background and then disappeared completely, leaving behind little evidence of its existence by the time the team celebrated its championship.

In this existence and disappearance, its story offers a sharp contrast to that of the team. Affixed in left field, it witnessed Bobby Balcena’s 26 doubles as the first professional player of Filipino descent, lurked behind the record-breaking 22 starters used by the team, and provided speculation for the astounding 342,000 fans who packed Sick’s that summer. Though both the box and the roster lasted but a season, the laughably impossible faded away, while the city for decades clung to the team, taking from it only the possible.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now