Away Flies The Boy

By: Matt Ellis

Popular discourse has a tendency, I think, to conceive of “media” as a particularly contemporary phenomenon. Sure, one could point to nineteenth-century newspapers and the emergence of photography, but when you hear the word what you think of is usually, like, some brain-dead millennial staring at his his iPhone playing Angry Pokemon or whatever, plugged into the dang Matrix and zonking out of experiential reality.

History, on the other hand, is supposed to be an immutable, a priori *thing* that informs everything that comes after. And yet, at the same time, what I find so fascinating as I’m starting this series on baseball and media, is the simple fact that the actual history of the game is only available to us through second-order mediation. It’s common knowledge now that baseball wasn’t invented by Abner Doubleday–that the famous “No Rounders!” calls were embedded less within a particularly modern development of cultural history than nationalism before the outbreak of that Great War which (should have) ended the concept to begin with.

History is supposed to be given to us from on high, and yet, famously, we don’t actually know from where the game of baseball truly emerged. Sure, there are predecessors: cricket, trapball, stoolball. And yet as resident MLB historian John Thorn has pointed out, the game has something of a “secret history” resting in documented history.

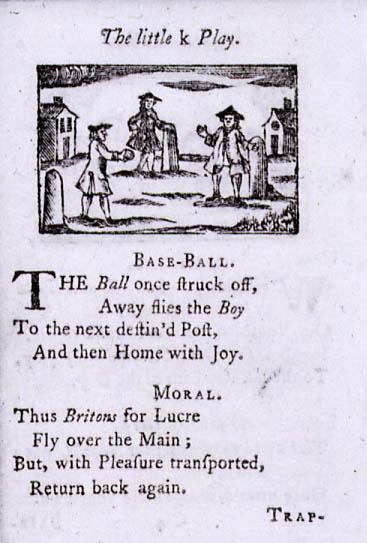

At once this might seem banal: this poem is read in the first episode of Ken Burns’ nine-hundred hour Baseball documentary, which predates Clinton’s second term, the War on Terror, and the Star Wars prequels. Just imagine what it would feel like to live in that world right now.

And yet at the same time, I’m struck by the simple fact that this famous eighteenth-century poem with its silly graphic addendum sits as a canonical founding document for the history of the game. Think about this for a minute: every single baseball game played at the top level in the 20th century has nearly every pitch recorded, each hit, each sacrifice bunt. A ball hasn’t been thrown in the past ten years without its velocity, spin rate, and vertical drop measured and indexed by a team of computer analysts: and what we have to thank for all this is a poem written in some old book.

At one level, this speaks to the fundamental contradiction at the heart of the game: a game which demands quantification while simultaneously effacing what can be known about it, the chance for magic utterly more active than any other sport. We know the name of the man who invented basketball, the institutions which solidified football are still giving out bachelor’s degrees. And yet, it’s not just the romantic notion that we don’t know where baseball comes from: that is utterly boring, and well-trodden ground. It is instead that its primordial history is only available to us through its mediation in other forms: poetry, songs, newspaper clippings. It is a history which demands not to be known, but rather imagined.

Gutting It Out

By: Patrick Dubuque

“Two bites of pasta, two bites of green bean,” I repeat, almost to myself, a sad mantra. We’re almost done. Two bites of pasta, two bites of green bean. My daughter stares at her dinner with the intensity of a prizefighter at the weigh-in, lips tight, unbothered by the fact that she’s been at it for half an hour already.

She will win. She always does. Soon it will be one bite of pasta, one green bean, then no pasta, then a bite of green bean that will be so small, such a mockery of the word “bite” as a term of measurement that I will feel more shame in her eating it than if I’d just quit. She has the advantage of infinite reserves of youth. She has not learned that terrible curse of adulthood, the compulsion to do things they do not want to do.

I did not want to go to work today. I did not want to get the code for my check engine light in my car. I did not want to eat green beans. I did not want to play Play-Doh, an activity that includes zero playing on my part and 100 percent keeping my two-year-old from eating said Play-Doh. I did not want to sit with my daughter under her bunk bed with the library book and explain to her that her cat was going to die next week. (“I will miss him when he’s gone,” she reflected. “And then we will get a new pet.”) I certainly did not want to write after explaining that my daughter’s cat was going to die. Yet here I am, writing about writing, tired and hacky, but an adult.

Most sports, the evolution of children’s games, feature a killswitch for the disinterested party: running out the clock in American football, garbage time in basketball, the king knocked over in a game of chess. Our sport of choice lacks such mercy, save for the occasional bottom of the ninth, but instead sends each player through nine stanzas of 162 consecutive trials, a millstone to grind them all down. Even in baseball, though, we see the usual metagaming of tanking and scouting prospects, artificial incentives to add meaning to meaningless September games. And the financial benefits of every home run are the same. So no final game of the season is ever truly pointless.

But if I could go back to watch pre-free-agency baseball, I wish, almost as much as witnessing the famous moments captured in the reel-to-reels, that I could have been there for October 2, 1949 at Sportsman’s Park, when Ned Garver and his eight friends threw an inning each to divert themselves on the last day of a hundred-loss season. Two second-division teams, fifty young men with nothing to gain except the right to go home, and the paying crowd that stood in their way like a contented mob.

The baseball game I imagine has nothing to do with reality, but instead floats in watercolor like a children’s book, a still frame of a season, a summer, a childhood refusing to end. I want to admire the players, not for their athletic prowess or heroism, but for their willingness to be there at all, to not just walk away. It’s not always easy, after all, being an adult.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now