Why the Hall of Fame Doesn’t Matter

By: Patrick Dubuque

One of the hard things about getting old, as a writer, is having to share the same name as yourself. There are some vocations where growth and change are accepted as part of the aging curve: teaching, perhaps, or carpentry. But as a writer, once your name is on something, it’s you, even if it’s not really you anymore.

Around this time in 2012, I wrote a piece for NotGraphs entitled “Why the Hall of Fame Matters.” I understand why I wrote it: as dumb as the Hall is, it’s also right in my personal wheelhouse: an institution designed to create meaning out of the game. The essay is, in retrospect, a small-L liberal paean to America, a statement of faith in our collective spirit, a grasp at some late-Heinlein ethereal “humanity” that we all check into on some level. The Hall, I believed, was not necessarily a representation of us, certainly not a democratic entity, but a sluggish mindless depiction of our will, the social values we unconsciously assemble.

It’s been a long five years. As Ryan Thibodaux’s vote tracker builds up momentum, and the radio boxes trickle past my twitter feed, each blank Edgar checkbox or vote for Omar Vizquel fails to stir in me the same feelings. With fifteen deserving candidates on the ballot, decoding the strategy behind each selection is too much. Meanwhile, Joe Morgan wrote his letter, setting the Hall’s standards for qualification and further divorcing it from any public ownership. Politically, both inside and outside the game, the idea of compromise has grown increasingly idealistic and unattainable. The Hall is not ours. Is the game ours?

In one sense, political disinterest is the goal of all tyrants; it’s much easier to seize control of power when the people abandon it. And I want a Hall to exist; I want there to be another celebration of the men who play baseball, something beyond a single champagne shower in late October. But this, what we have, isn’t it. We used to settle for waiting out the golf writers who clogged the sport, but the writers are no longer the problem. The Hall itself, between the character clause and the refusal to expand the vote or provide transparency in its voting, has decided to define itself, rather than allow itself to be defined by the sport’s life force.

What do you do when the people who are supposed to represent you decide not to? We can tear the buildings down, or give up and allow ourselves to be governed. But my instinct, in 2017, is to reject both: to pull back, to return to the local. I’ve long believed that there shouldn’t be a Hall of Fame, but a hundred Halls, one for every city, celebrating its own heritage. Rather than trek out efficiently to Cooperstown to bathe in it all, fans could take pilgrimages, visit the houses that each great ballplayer built. The people in each town would decide who belonged in it. And it, in turn, would belong to them.

What we have now, this gerrymandered collection of racists and heroes and drunkards and men named Rabbit, is just sponsored content, a wall full of bronzed #facesofmlb.

Who knows how stupid this will all seem in 2022. I apologize on that Patrick Dubuque’s behalf.

A Trio of Turkeys

By: Zack Moser

There are three professional baseball players who have gone by the name “Turkey.” One is rather famous; the other two toil in obscurity. One was one of the best players of his generation; the others had more ephemeral careers. These three are Turkey Gross, Turkey Tyson, and Turkey Stearnes.

Gross, born in Texas four years before the turn of the century, played eleven minor league seasons in addition to his brief stint with the Red Sox. Starring in the Texas League with the San Antonio Bears, Gross hit for a high average and played good defense. He died young—Gross succumbed to pyelonephritis at 39—and is remembered primarily for his (admittedly pretty funny) name. Turkey is kind of gross, my friends.

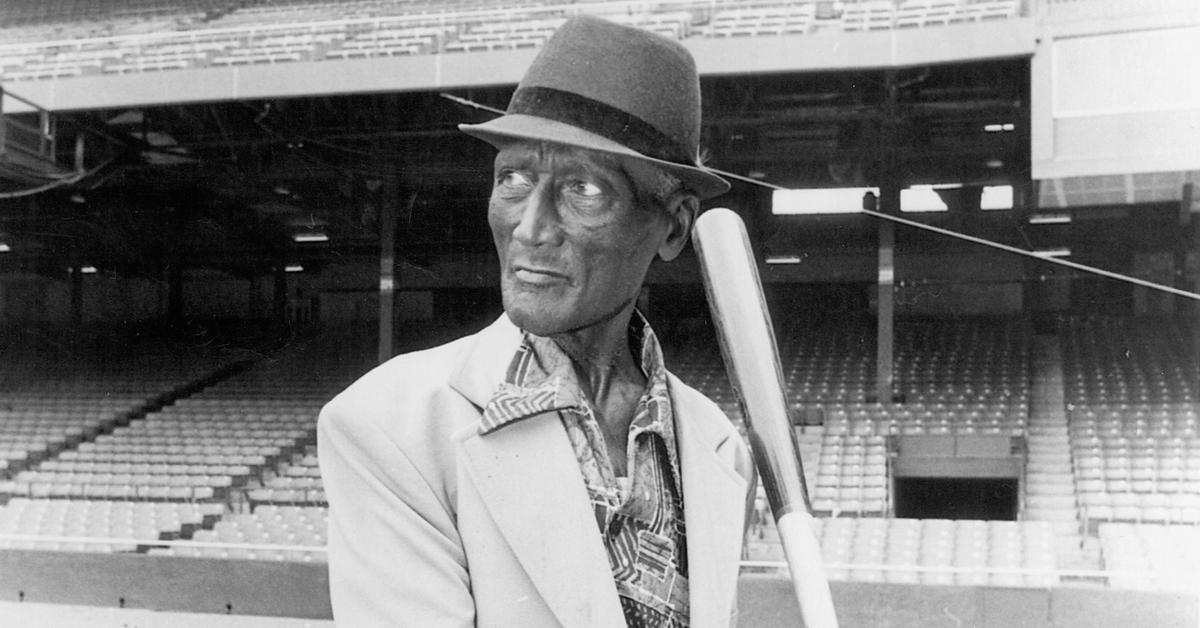

Stearnes played pro ball through his age-39 season. The Tennessean regularly hit in the high-.300s, topping .400 a few seasons, and hit for some power early in his career before becoming primarily an average-oriented hitter. First-hand accounts of Stearnes’ play relay an unorthodox running style (whose resemblance to the bird was the progenitor of the “turkey” name), but true skill in all five tools. The outfielder didn’t stay put as did Gross, with significant tenures in Detroit, Chicago, and Kansas City, but he never played in a major-league game due to his race. Stearnes played one full generation before Jackie Robinson debuted for the Dodgers, beginning in 1920 and retiring in 1940. He’d never get the opportunity that Gross had.

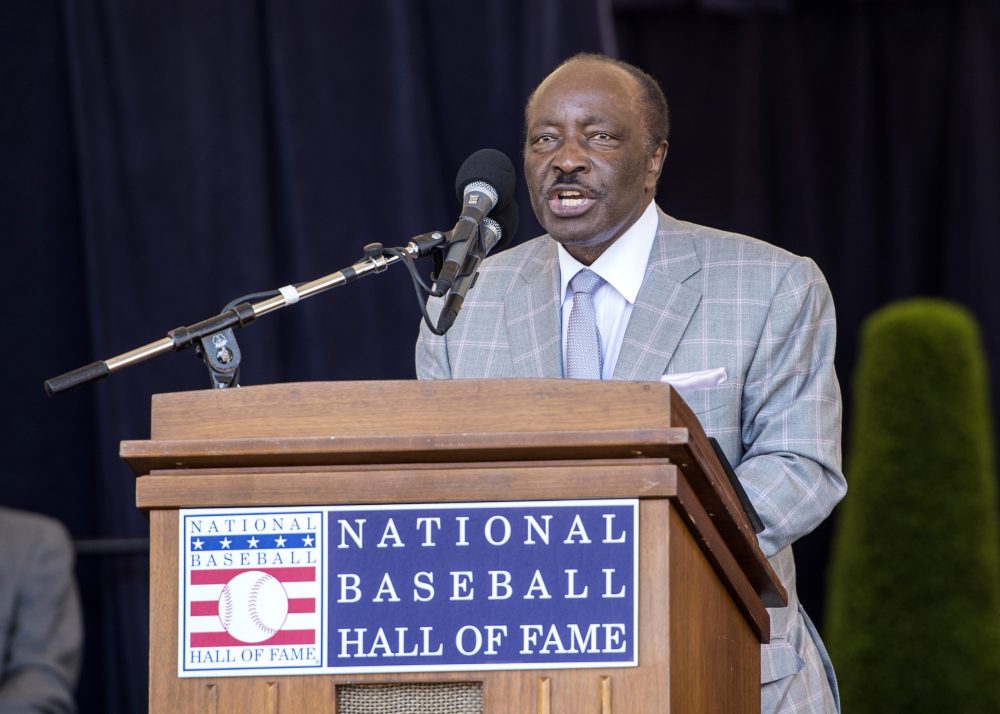

Stearnes did appear in a few East-West Classics, the Negro Leagues’ all-star game, and was feared more than most hitters during his career. The star also boasted a unique relationship with his bats, to whom he sometimes talked, and often swapped bats of different sizes to deploy in different situations. After his playing days, he returned to Detroit, where he would die four decades later in 1979. Stearnes then entered the Hall of Fame two decades after his death, only the 17th player to spend most of his career in the Negro Leagues to gain induction.

The last of the poultry trio is Turkey Tyson, bringing to mind both Thanksgiving meals and frozen chicken tenders. Tyson played for the 1944 Philadelphia Athletics and received precisely one at-bat.

As with Gross, Tyson is a historical anecdote remembered primarily for his name, rather than his skill. Stearnes, however, shined for 20 seasons, and caused pitchers to quake in their shoes and hitters to curse their bats because Stearnes always seemed to track down their flyballs. In retirement, Stearnes worked as an auto mechanic with a company owned by Walter Briggs—the owner of the Detroit Tigers. Briggs’ Tigers, playing in his eponymous stadium, didn’t employ a black player until 1958, after even Robinson’s major-league retirement, with Ozzie Virgil becoming the pioneer than Stearnes could have been decades earlier. Stearnes is now enshrined not only in Cooperstown, but also outside of the center-field bleachers at Comerica Park, with a plaque installed 87 years after his professional debut.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now