Two outs. Runners on. October. These are the moments when the batter and pitcher rush to the airtight door, strength against strength, Will a flood of runs rush in? Or will the door slam just in time? As much as any other, these are the situations where the effects of much-discussed strategic developments like bullpenning (or, you know, calling on a Cy Young winner in relief) tilt the playing field.

They are also the moments where Twitter traditionalists—self-styled experts educated in their kid’s Little League dugout—pop up to mourn the death of situational hitting, and the rise of swinging for the fences. Strikeouts are on the rise. Homers are up. It all comes from valid reasoning about how to play the game optimally, you explain. But it nonetheless changes the dynamic of a key plate appearance against Andrew Miller or Max Scherzer. The 2017 regular season did nothing to divert the snowball effect of those trends—and the past few postseasons have done nothing but accentuate them.

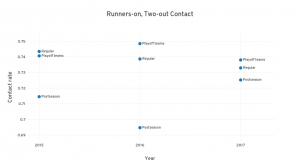

You’d be unsurprised to see that the contact rate in these two-out, runners-on situations has dipped even further over the past two Octobers than it has over the past two regular seasons. But you, and the small-ball apostles in your timeline, may not believe which way the 2017 postseason is trending, or which clubs are driving the uptick.

What you’re looking at there is a chart showing the contact rates over the past three seasons for:

- The whole league’s regular-season average

- The regular-season average of just that season’s playoff teams, for comparison’s sake

- And the average in postseason play

(All 2017 statistics you see here and throughout the article are through the conclusion of the Division Series.)

Hitting in big postseason spots is, logically, more difficult than hitting in those spots during the regular season. The accelerating changes in pitcher usage would lead us to believe the gap in contact should continue apace, or perhaps even grow. So why has it shrunk so noticeably this year? First, we must note that while the contact rate in our given situation has jumped up, the strikeout rate is still rising—27.6 percent of plate appearances in runners-on, two-out situations have ended with a K. That’s up from 25.5 percent in the 2016 postseason.

But the results! The results look to be tracking more with contact rate. Postseason hitters slashed .184/.290/.317 in last year’s big situations, while they are hitting .247/.352/.400 in 275 plate appearances thus far in 2017. The OPS for all runners-on situations, for reference, has jumped from .659 last October to .789 this month. Taken together, it betrays a potential trend in the making: Hitter pushback, through a contact-focused approach to situational hitting, or clutch hitting, or whatever it is you want to call that tense meeting at the threshold between runs and disappointment.

***

In one way, and one way only, the increased contact rate in these situations is easy to explain: It’s the Astros and the Cubs, skewing the curve like the overachievers in your calculus class.

| Team | Pitches | Contact% | Swing% |

| Astros | 140 | 83.8% | 48.6% |

| Cubs | 126 | 80.6% | 57.1% |

| Yankees | 227 | 75.0% | 44.1% |

| Nationals | 170 | 70.8% | 42.4% |

| Red Sox | 105 | 70.4% | 51.4% |

| Indians | 82 | 68.2% | 53.7% |

| Diamondbacks | 85 | 61.0% | 48.2% |

| Dodgers | 101 | 60.4% | 47.5% |

In the two-out, runners-on tendencies for postseason teams (excluding those that played only one game), these two clubs stand out. The samples are noted because they are small, but it’s striking how well these two clubs, very recently examples of slugging-focused, strikeout-accepting hitting philosophy, seem to be making strides toward sustaining innings through contact. Or at least giving themselves a better chance at it. So how are they doing it?

Well, for one, when these young squads made their respective well-covered free agent decisions, each chose to diversify. For the Cubs, it meant Ben Zobrist and Jason Heyward. For the Astros, it meant Josh Reddick. Whether this particular bit of his profile factored into Houston’s decision is anyone’s guess, but since 2015—shortly after a dramatic drop in his strikeout rate—Reddick slashed .332/.406/.534 in these moments across 264 PA. For reference, the league put up a .240/.328/.400 line this season, and in our slice of the postseason so far, the line has been a very similar .247/.352/.400.

If you’re skeptical of Reddick’s numbers being a reliable foothold on some real skill, I hear you. We’ve seen enough research to know that bring a good “clutch” hitter often means little more than being a good hitter with helpful cosmic timing. But it’s possible to put stock in his proclivity to make contact without projecting his excellent results to continue uninhibited.

And if a team were trying to devise a plan to help its lineup deal with October’s barrage of excellent pitchers barricading the path to every scoring opportunity, might it place a greater emphasis on contact than in the regular season?

While it’s too early to draw conclusions, we may be witnessing the implementation of more aggressive tactics—situational hitting, if you will—with an eye toward putting the ball in play.

Here are the pitchers who were on the mound for the 10 highest-leverage two-out, runner-on plate appearances of the postseason thus far: Aroldis Chapman, Cody Allen, Mike Montgomery, Chapman again, Joe Smith, Jon Lester, Andrew Miller, Craig Kimbrel, Chris Sale, and Charlie Morton. With maybe two exceptions, yikes! These at-bats just aren’t comparable to the generic, cross-section-of-600 specimens we examine as little moving pieces of a whole season.

Reddick’s plate appearance—against Kimbrel in ALDS Game 4—was one of those 10. It was one of six to conclude with a ball in play. It was the longest at-bat, and it was the only hit. Teams must be asking how they can best stave off the seemingly inevitable wave of strikeouts when these sorts of pitchers show up for these sorts of battles.

The Cubs may have decided to try swinging early and often. While the Astros were one of the least likely teams to whiff themselves out of innings in the regular season, the Cubs were middle of the pack. In the postseason, the number that stands out is the swing rate. Cubs hitters were hyper-aggressive with runners on and two out against the Nationals.

Addison Russell, the Cubs’ shortstop, struck out in 29.4 percent of his 85 chances in this moment during the regular season (which brought his career rate to 27.1 percent). With the Cubs trailing 4-3 in Game 5, and Max Scherzer on in relief to bar the door, Russell swung at the first pitch he saw. What’s strange is that Scherzer started him with a changeup, in and moving toward his hands. It doesn’t seem like a pitch he would be sitting on, and the juuuust-inside-the-line grounder supports the idea he was in front of it.

But it worked. It worked so well that the very next inning, Russell came to bat again with two outs and a man on. The Cubs had the lead at this point, but Russell swung away at the first pitch again, and in doing so, illustrated why all outs are not created equal in these moments: Because sometimes, an out isn’t an out.

There’s also the hitter who has adapted, Anthony Rizzo. He’s taken up the Votto-esque tactic of choking up to seek out more contact in two-strike counts. In 2017, he cut his strikeout rate, and his two-out strikeout rate, and his runners-on, two-out strikeout rate.

Rizzo is not trying to end the inning without the defense retiring him. Sure enough, he didn’t strike out in five such trips to the plate in the NLDS against Ryan Madson, Stephen Strasburg, or Oliver Perez, the veteran whom he faced in his highest-leverage moment. He also swung at the first pitch, and he didn’t hit it hard. Yet, it worked.

The list could go on. Had the Nationals advanced, Michael Taylor and his two first-pitch successes against Wade Davis might be standing as shining examples of aggression as salve for vulnerability.

The question, then, is whether the more frequent contact will continue into LCS and the World Series, and whether the aggression will continue in these run-scoring opportunities. And like the broader conundrum of clutch hitting, there’s no clean answer. There’s a variation on the time-honored tradition of wondering how This Guy or That Team will respond when put to the test. And there’s the incredibly simple logic that taking more cuts gives you a better chance at putting the ball in play against more potent arms.

There’s also a chance the contact-driven rally of the hitters goes sideways before it even becomes a thing. The Yankees are so far one of the least aggressive postseason teams of the past few seasons in our given situation. The Cubs came out swinging last October, too, before sitting back more and more as their run went on. The Astros and Dodgers may behave differently when they encounter more intense game situations than they ran into during LDS victories.

What’s obvious is that the degree of difficulty is not going down when runners are within spitting distance of becoming precious postseason runs. If the pitching tactics are going to continue to diverge from their regular tracks, as we all seem to agree they will, it only makes sense for the overall offensive strategy to go a different way, as well—even if you hear an old-school I told you so in each crack of the bat.

Thanks to Rob McQuown for research assistance.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now