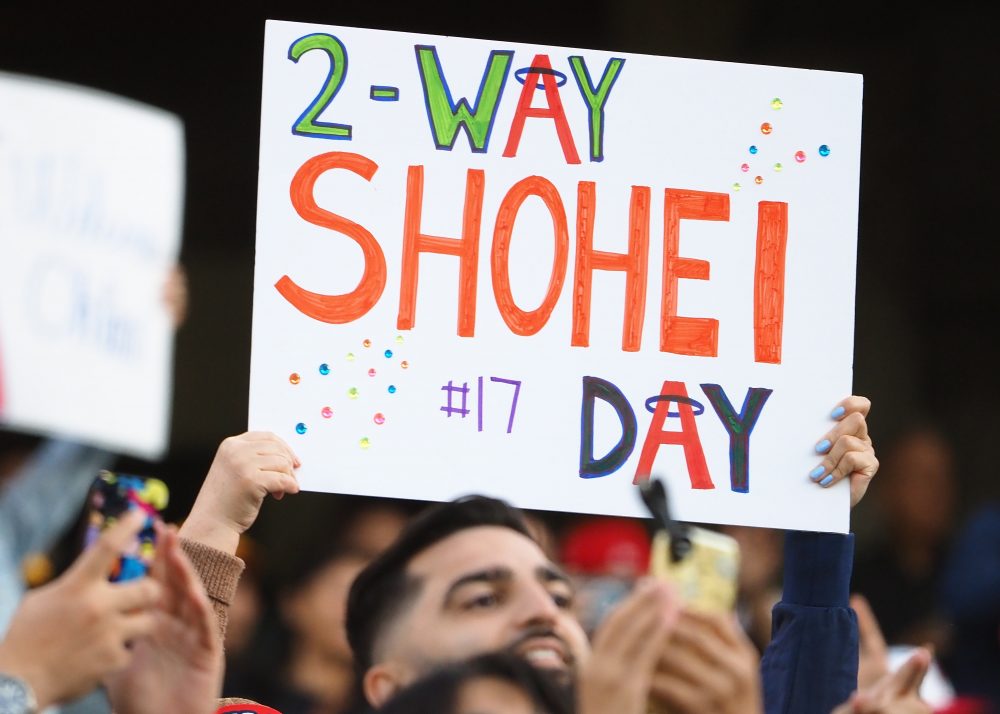

Welcome to Ohtani Week: a celebration of, well, Shohei Ohtani. There’s been no player more fascinating or exhilarating since Ohtani graced our shores in 2018. Over time, the initial curiosity and excitement surrounding MLB’s first true two-way player in a century morphed into something more: Pure, uncut awe derived a superstar breaking barriers previously thought unreachable. All week, we’ll be talking about the most lovable—and possibly most talented—man in baseball. So throw on your Angels cap, grab your laptop charger, and dig in.

Over the course of this last week, we’ve said a lot of things about Shohei Ohtani here at Baseball Prospectus. We’ve highlighted his incredible athletic achievements on both sides of the ball, we’ve discussed the subtle advantages he provides beyond the superlative ones, but in some small way, Shohei Ohtani’s accomplished something even more difficult than hitting a baseball 513 feet.

I’ve written a small amount about my fractured relationship with baseball, mostly for myself, but it’s difficult to write about the absence of something in the same way one can produce thousands of words on its presence. Over the years, I’ve reflected on how I grew up with the game, developed as a fan of it (but was never allowed to join), came back to it in college, became a primarily self-taught evaluator with enough good sense to seek out expert opinions, and came within a few dollars (an hour) of working for a team. I’ve always been a bit of an over-sharer (see: my entire Twitter presence), in life as in writing, but something’s kept me from talking about the way that both slowly and all at once, baseball went from something I couldn’t imagine my life without to a non-entity.

This isn’t meant to be a column about burnout, though I can’t write about Shohei Ohtani[1] without talking a little bit about burnout. Here’s a fact: I didn’t know Shohei Ohtani’s[2] home run total until it was in the double digits. I knew he was having a good season, a prove-them-wrong season, but I had little idea of the context (or, really, exactly how historical his season was shaping up to be).

The inciting causes of my baseball burnout are many, and too complicated (and personal) for what should be a joyful celebration of a phenomenon, but together, they added up towards a dreadful apathy[3] towards the game. When one doesn’t have the time or inclination to obsessively check Twitter for updates, the time to watch or attend games in person, or the ability to handle the frustration that comes with yet another Major League Baseball-led bungling of the management of the sport, it can quite simply be hard to care.

Ohtani breaks through that indifference. If Major League Baseball knew what was good for them, they’d learn from every single aspect of what makes him a star. Ohtani got me to watch the All-Star Game, something I didn’t watch even when I was making most of my income writing about baseball. The promise of Ohtani induced people who have never loved the sport to turn on their televisions during the Home Run Derby and tweet incredulously about watching baseball. Some of them kept watching even after he and fellow young star Juan Soto finished putting on a show the likes of which we haven’t seen, and were introduced to not only Soto, but one-man inspirational story Trey Mancini, “no thoughts just dingers” Pete Alonso, and, negatively, the way that shaky and sanctimonious broadcasting can make or break the presentation of the game.

How long has it been since a baseball player was a household name for their game, and not for other associated notoriety? Alex Rodriguez was undeniably great[4], but did we know him for his greatness, or for other reasons? Possibly Derek Jeter, though one could argue his fame actually oversold his baseball ability, hovered over it like a heavy-handed metaphor, particularly at the end. Even polling various baseball minds, both employed here at Baseball Prospectus and elsewhere, the generally agreed-upon names of Barry Bonds, Sammy Sosa, Mark McGwire, Ken Griffey, Jr, and Reggie Jackson all had their primes more than 20 years ago. [We’ve absolutely had stars in Ichiro Suzuki, Mike Trout, and to some extent players like Bryce Harper and Clayton Kershaw, but even their popularity has felt either more centralized to their home team, or towards a fevered appreciation by the baseball community.]

There’s certainly something about the singularity of what Ohtani is doing. It’s one thing to be a two-way player in a sport that has abandoned the idea. It’s another thing entirely to be so good at it that your achievements leap off the screen and into the face of someone who had just about given up on the sport altogether.

It says a lot that Ohtani has been able to overcome every roadblock to stardom. Insistences that he can’t be the “face of baseball” because he wasn’t born in the states (read: isn’t white), because he’s playing the game a different way, wasting some imagined productivity by refusing to specialize, that he’ll alienate fans—all that has been pushed to the side by how transcendentally good he is at the game. While it shouldn’t take being one of the best players we’ve seen in generations to earn the begrudging respect of the powers that be because they’re the powers that have always been, his talent has allowed him to bypass the gatekeeping and enchant the average Twitter user[5].

Maybe Ohtani’s legacy will not just be the joy he brings us now. Maybe it will be that the next time a player says they want to pitch and hit, they’ll be judged on their actual talent, and not just our preconceived notions and preset training regimens. Maybe the next time a burgeoning star graces our domestic league with their presence, they’ll be celebrated from the outset, and promoted with the same grace MLB allows our “homegrown” players to be promoted. The grace to have a bad season and have it chalked up to development, not disappointment. Not every player in those situations will have to be Ohtani, in the end. It’s enough that they could be, and should be allowed to be.

Who knows? Maybe in the long run, the best thing about Ohtani won’t just be the Derby dingers, or the accolades he’s sure to garner. Maybe it will be that he’s shaken up a stagnant game, and made Major League Baseball exciting, in spite of itself.

[1] Also, a brief aside: It’s impossible to refer to him as anything but “Shohei Ohtani” in anything outside of the most pure of journalistic styles. For some, the mononym is the height of recognition – and sure, we’re not likely to get him confused with any other Ohtani, but there’s something in saying both names. Something about a respect he’s due. Weirdly, Ichiro’s mononym feels the same.

[2] Okay, at this point is when it gets pretentious.

[3] Major League Baseball’s insistence on completely botching every last aspect of game presentation, marketing, and management has a lot to do with that, as it simply came to be too much to watch the men in suits ruin the game I loved, and I haven’t even gotten started on sexism and racism yet.

[4] Time to make us all feel extremely old: The whole A-Rod thing that started with his move from Seattle to Texas? Twenty whole years ago.

[5] Because the average Twitter user doesn’t want to hear the awful truth, they just want to see some dingers, and in this case, the dingers are on the side of reasonableness.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now