Pitchers are bad at hitting. By the time you finish reading this article, they’ll be even worse: the decline of pitcher offense is one of the most consistent trends in baseball, along with rising strikeouts and increased playoff entrants. We live in a specialized world, and with every resource and moment devoted to improving their primary function, pitchers don’t have the time or the energy—or even the specific training regimen—to improve their hitting. Someday their collective true average will spiral toward its natural asymptote of zero, and the traditionalists will face the difficult decision to rescind their privileges. In the meantime, National League baseball will remain a chess match, one where both players give each other knight odds.

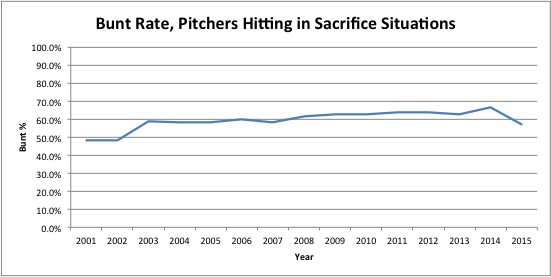

Fans may still adore seeing pitchers hit for themselves, but NL managers have a different idea entirely. They aren’t taking the bat out of their hands, just their ability to swing it. Consider the following graph (and ignore the final inconvenient point, which we’ll return to):

It makes sense. If pitchers can’t be relied upon to even make much contact with the ball, let alone do something valuable with it, the next best thing is to take the productive out when it’s presented. Sacrifice bunting with the pitcher has become something of a maxim, a guide for smart baseball: the team moves the runners, avoids catastrophes, and prevents their fragile hurler from tripping over his own Achilles tendons on the base paths. It’s the perfect strategy.

In game theory, however, there are rarely perfect strategies.

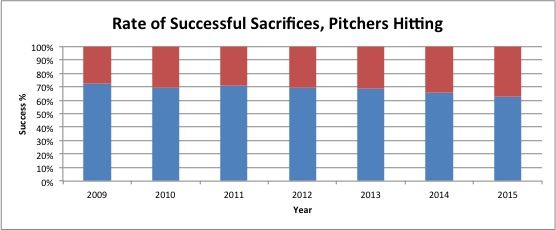

Success rate, as defined in the above graph, is any result which advances at least one runner, and also includes singles and reaching on error. Any play that fails in this goal, whether by forcing out the lead runner, striking or popping out, or leading to a double play, falls into the red part of the bar.

Pitchers are getting worse at bunting, almost as consistently as they’re getting worse at hitting. It’s easy to chalk this up to the same cause of their hitting woes, and there’s almost certainly some truth to this; there’s also the problem of predictability. In an ideal world, bunting should present one of baseball’s purest examples of game theory: with each batter, the defense will align itself at exactly the point where the added difficulty of fielding a ground ball is equal to the increased odds of making a play on a bunt. The hitter, knowing his own heart and talent, will then try to be as unpredictable as possible, while taking whatever odds the defense gives him.

In this scenario, there is no one right way; or, rather, the right way is not to have one. Become too predictable, as pitchers now are, and it allows the fielders to cheat. But this is not the pitchers’ problem; they are being given information, and now they must figure out what to do with it. If pitchers are bunting too often, what should their opponents do about it?

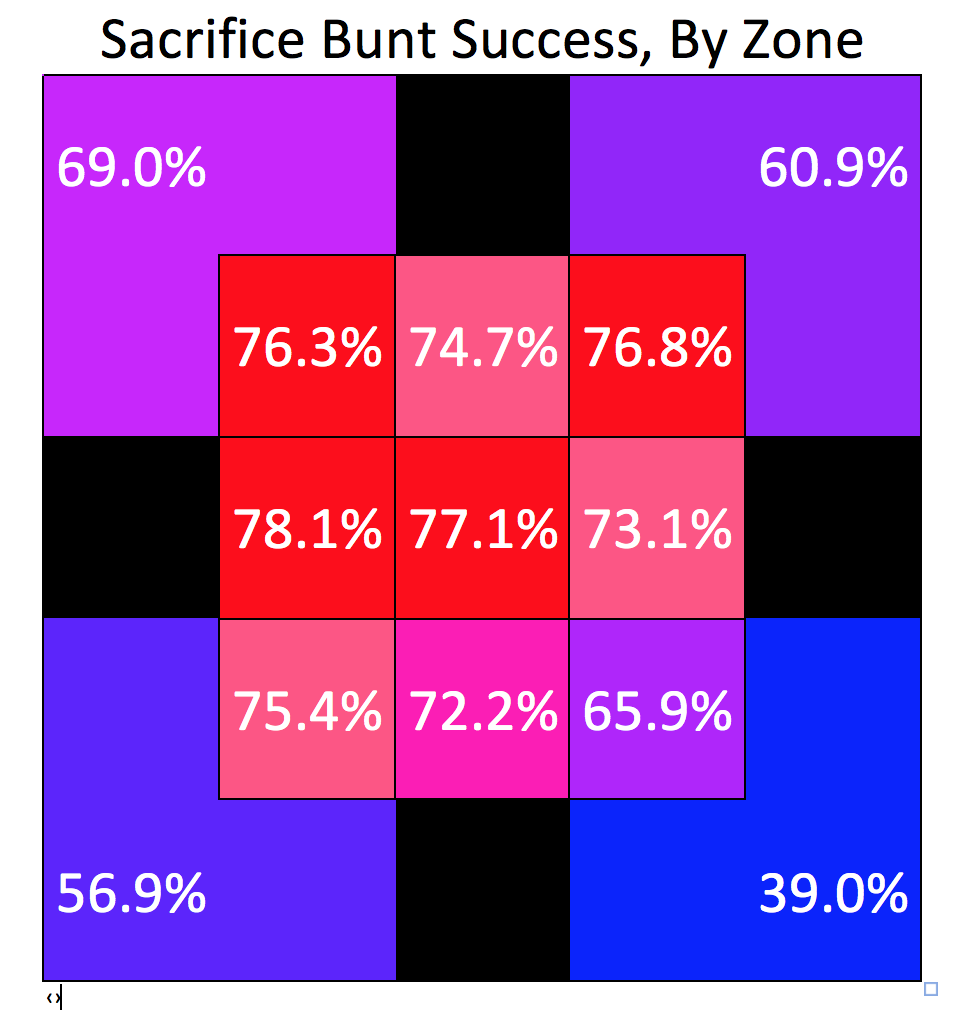

The first instinct would be to throw more pitches up in the zone. A bunt that rolls along the ground allows the runners to run; a bunt that soars into the air not only freezes those runners, it also increases the likelihood of a pop-up or even a double play. But this, too, is a lie.

Unsurprisingly, pitches out of the zone are more difficult for pitchers to bunt well than those over the plate; the vast majority of the results are missed bunt strikeouts and fouled third strikes. Less intuitive are two other facts: that low pitches result in less successful bunts overall than high pitches, and all zones in the plate are more or less equal. It is true that high pitches do evoke more pop outs, and slightly more double plays (33, as opposed to 26 low). But this is countered by the fact that low pitches garnered far more strikeouts.

Those purple and blue boxes above are somewhat misleading, because they only include bunt attempts; they do not reflect the rate at which the hitter pulled the bat back and took the ball. Therefore, just as with every other type of pitching, it’s best to make the hitter chase as long as you can make sure he will.

It’s the second discovery that is the most interesting. Unlike with ordinary pitching, it’s not necessary to paint the corners against the bunt-crazed pitcher. Throwing down the middle is only incrementally worse than burying it low and away. It’s not what the pitcher does that ends up making the difference: it’s how he does it.

The average fan tends to treat bunts the way they do five-foot putts or free throws: automatic. A single missed bunt, in a clutch situation, will send them foaming over the stupidity of bunting, if he or she is generally younger, or over the laziness of the athlete, if he or she is not. But bunting is hardly as easy as it looks on television, and has one particular disadvantage over other sports: it is not performed alone. The opposing pitcher has some say in how easy that bunt will be, and the best tool they have in doing this is by making the ball bend.

It stands to reason that it’s harder to make accurate contact on a pitch with movement. And yet there’s almost a code of honor among pitchers that they throw each other fastballs; to do otherwise is unsporting, like playing Stratego against a six year-old. The other, perhaps more pertinent, fear is that it’s harder to throw strikes that way, and there’s nothing worse than giving up a walk to such an undeserving fellow.

Either way, the numbers tells us that pitchers throw more fastballs than they do to non-pitchers, even though they’re more successful against them:

|

Total Pitches |

||||||

|

+ |

o |

– |

— |

Total |

||

|

Fastball |

149 |

3027 |

1055 |

70 |

4301 |

|

|

Offspeed |

12 |

257 |

125 |

6 |

400 |

|

|

Breaking |

15 |

415 |

488 |

11 |

929 |

|

|

Unknown |

4 |

90 |

38 |

5 |

137 |

|

|

Rates |

||||||

|

+ |

o |

– |

— |

Total, P |

Total, Non-P |

|

|

Fastball |

3.5% |

73.8% |

26.2% |

1.6% |

74.6% |

63.9% |

|

Offspeed |

3.0% |

67.3% |

32.8% |

1.5% |

6.9% |

12.9% |

|

Breaking |

1.6% |

46.3% |

53.7% |

1.2% |

16.1% |

23.4% |

|

Unknown (#sss) |

2.9% |

68.6% |

31.4% |

3.6% |

2.4% |

0.0% |

|

Legend |

||||||

|

+ |

all runners, including batter, advance |

|||||

|

o |

some runners advance (sacrifice) |

|||||

|

– |

no runners advance |

|||||

|

— |

double play |

|||||

It’s especially perplexing given that a) the opposing pitcher is far less likely to punish a hanging breaking ball into the seats, and b) those curveballs don’t need to sneak around the black of the plate. As we can see, there’s not much harm in throwing that slider dead center; and if the pitcher misses, it’s actually to his benefit. Either way, he’s more likely to find himself a few hundredths of WPA richer by the end of the at bat.

Earlier I told you to ignore a data point. It seems through the first half of 2015, after 15 years of steady progress, pitchers have completely reverted in behavior toward the sacrifice bunt. It’s unclear whether this is a response to the third baseman eight steps in on the grass, or the modernization of managerial strategy long overdue, or just 700 plate appearances worth of noise. What we do know is that it hasn’t helped: pitchers are still just as lousy at hitting as before. The wise pitcher is the one who, when it’s his turn on the mound, remembers that fact.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Second, he also doesn't want to throw a wild pitch that will advance the runners before the bunt can even be laid down. Catching an errant breaking pitch can be tough enough, but it gets even more difficult when the batter is squared around with a bat in front of the catcher's eyes, blocking a clear view of the incoming pitch.

So, perhaps the defensive strategy is to throw a good fastball and accept the sacrifice with the occasional good fortune of a pop up, double-play or strikeout. It's a conservative strategy, but not necessarily a bad one.